I.

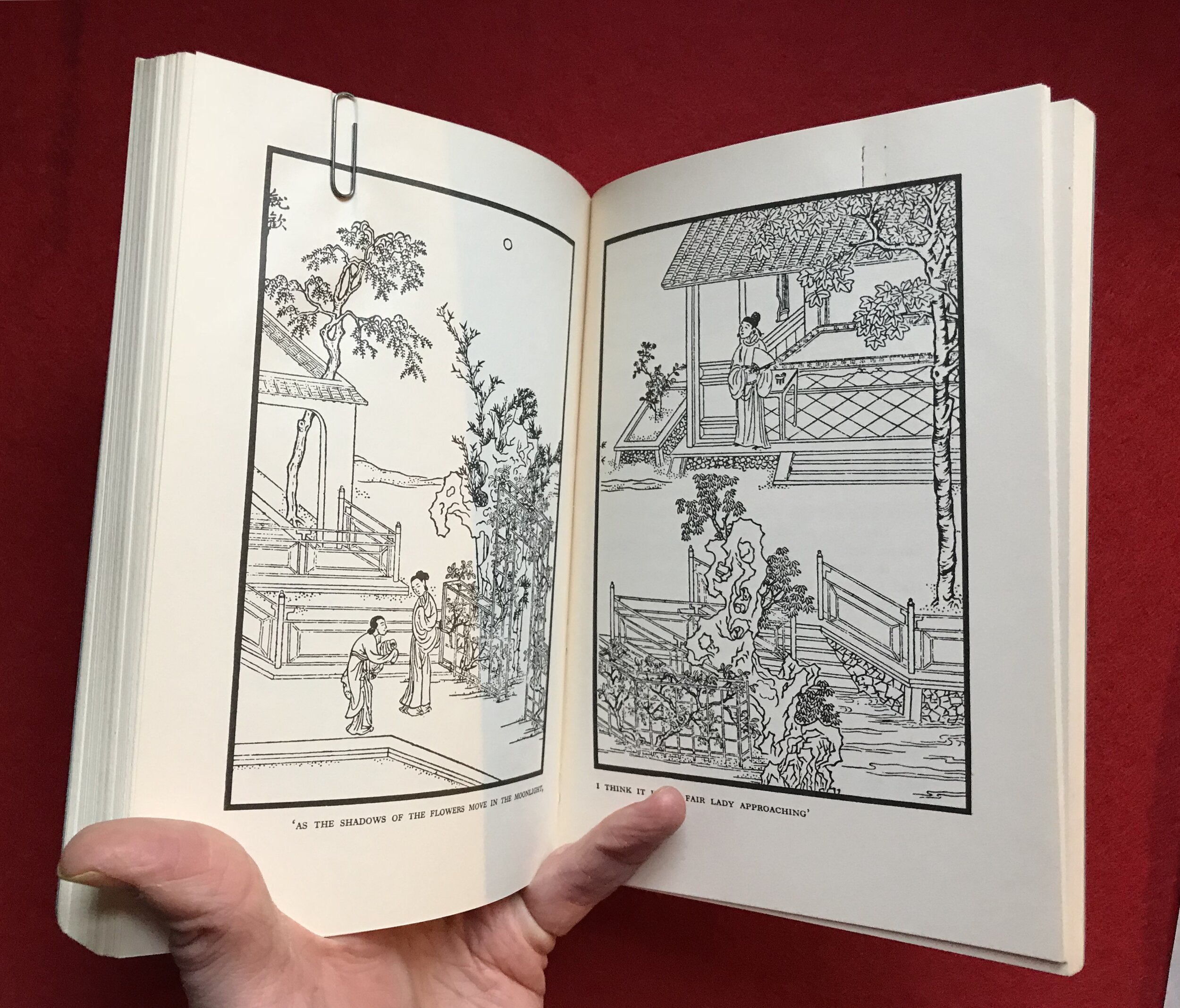

Books can transport you and provoke you. They can record a vision of the past. Books can also connect us with the creator, sometimes so deeply that we feel as if we are in direct communication with them. The book — its paper, its design, its entire history — can disappear as the mechanical process of turning a page becomes a nearly unconscious activity, like breathing or riding a bike. We become absorbed into the book.

While this alchemical process of turning rags or pulp into connections and imagined environments can be a welcome and beautiful kind of magic, in reality, the book is an object and one with many creators, craftspeople, and handlers (the historical study of the book as object is called bibliography). In this reality, we should consider ourselves more as "users" of the book as opposed to "readers," as the bibliographic scholar Sarah Werner states in her book Studying Early Printed Books . As we become conscious of the many hearts, minds, and hands it took for a book's production and dissemination, the community* appears via the book. We are transported out from the book.

*I am aware of this essay’s anthropocentric focus, which merits this disclaimer: it is most important to remember and respect the natural history of the book's physical matter; after all, the majority of the matter came from something once living - the tree, the cow, the lamb, the plant. There is, too, at all times, non-human interventions that literally keep the book alive: spores and bacteria, for instance. But I digress; this thread for another time.

II.

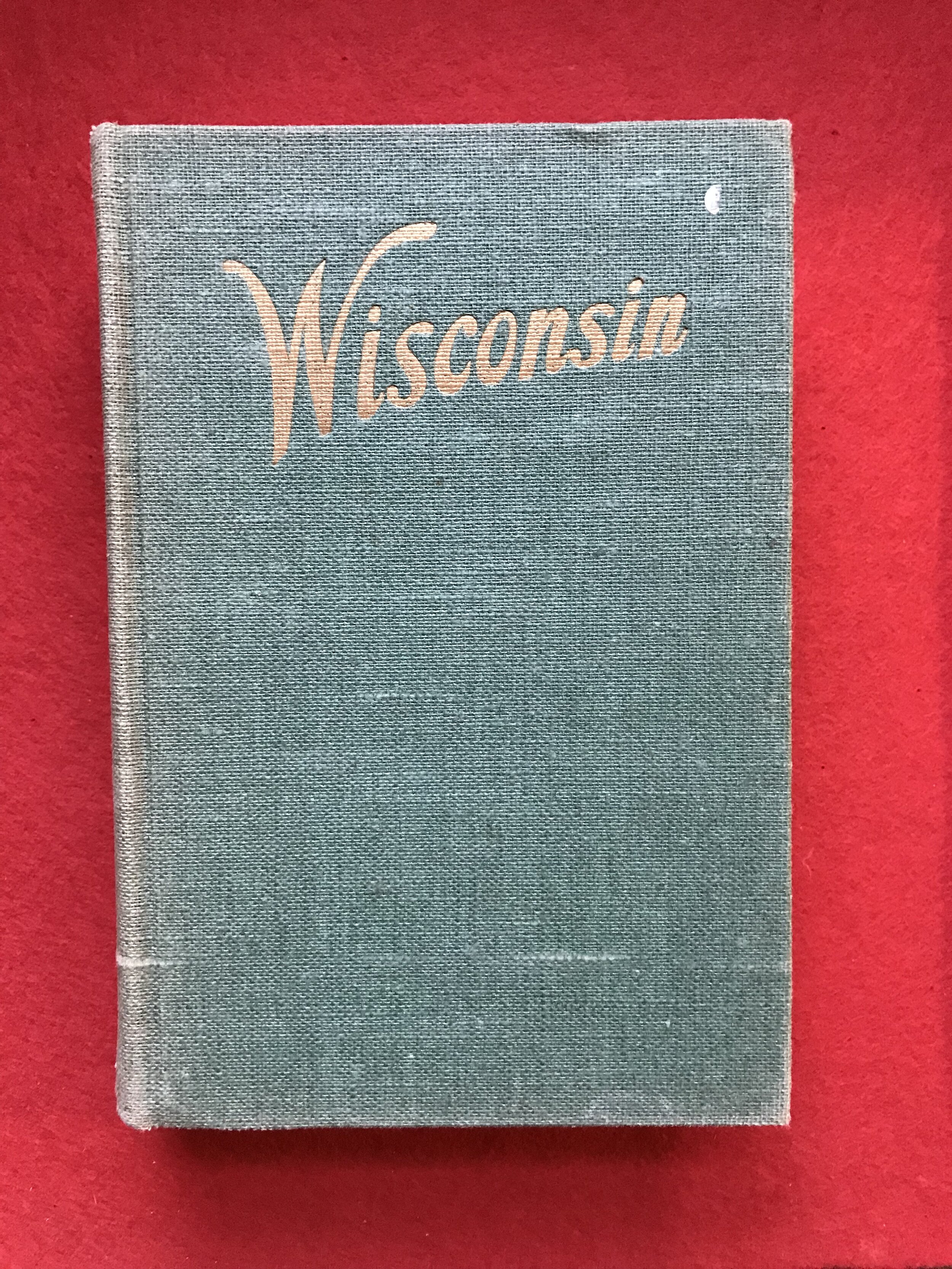

Looking at a book as a bibliographer might — where you consider its printing, publication, editions, and human interaction — you start to appreciate the individuality of the object. Yet, as most of us do not approach books as specialists, we often neglect this history. This is the partial result of consumer history; as scholar Leah Price writes in her book What We Talk About When We Talk About Books, the standardization of the book's form and production "made it possible for books to be branded and advertised at a time when most objects were handmade and locally sold." The trend in book production, from bespoke and individualized to standardized and anonymous, would eventually shift and transform the world's market and allow for an explosion in production and consumption. The market-driven rush to uniformity might have brought us a more robust capitalist system*, but it also created the illusion of copies and duplications, thereby distancing us even further from the individual books’ lives and their connected communities.

An early printer’s workshop

Nearly extinct are the days where pullers, pressman, beaters, press devils, and vatmen employ platans, tympans, quoins, friskets, formes, chases, and congers to make foolscap, demy, and bind them into sammelbands, quartos, 12mo, and 16° tomes where they have been stab-stitched, or gauffered, or dos a dos'd or tête-bêche'd**. Antiquated are the days of stereotyping, monotyping, linotyping, engraving, etching, rotogravure, lithography, aquatint, and cloth binding. Some even argue that our contemporary structure of physical print; of automation, inDesign, digital, heat-set web offset machines, and espresso print-on-demand machines are headed the way of the dodo and will be replaced by digital print culture (with the even more hidden designer and coder). No matter the book’s future, we become increasingly detached from its communities because there are seemingly fewer and fewer people involved in the book’s creation and circulation.

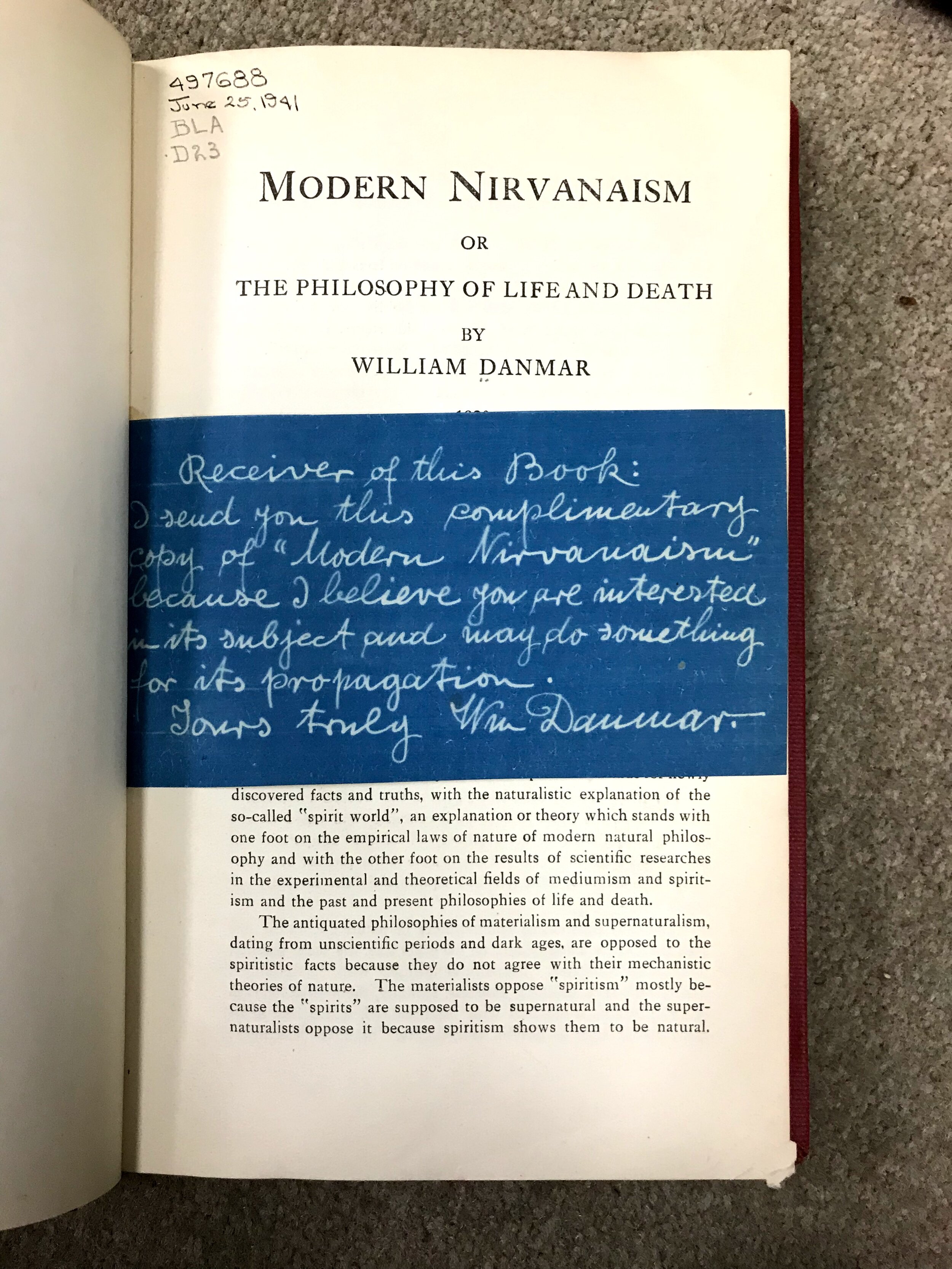

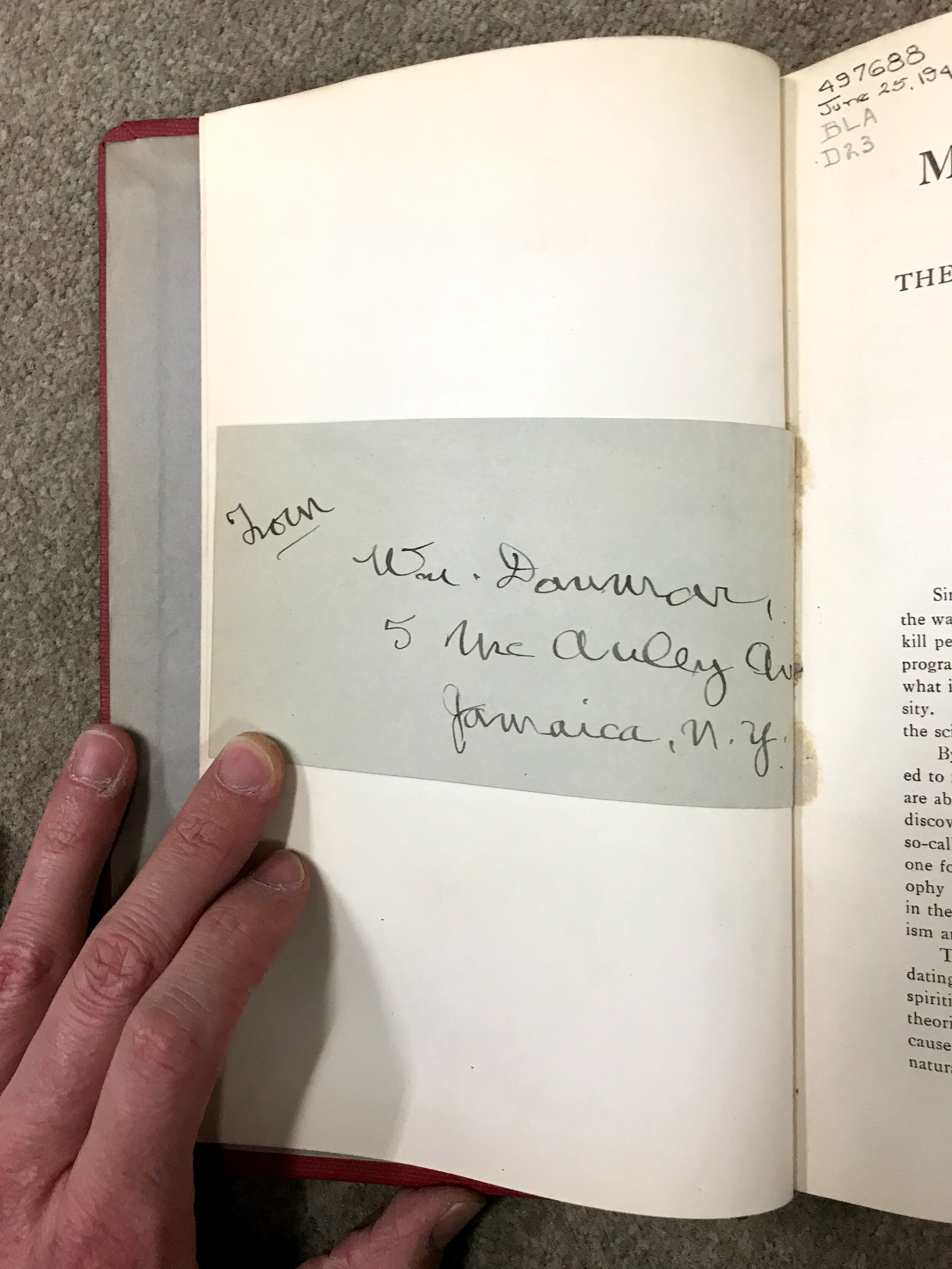

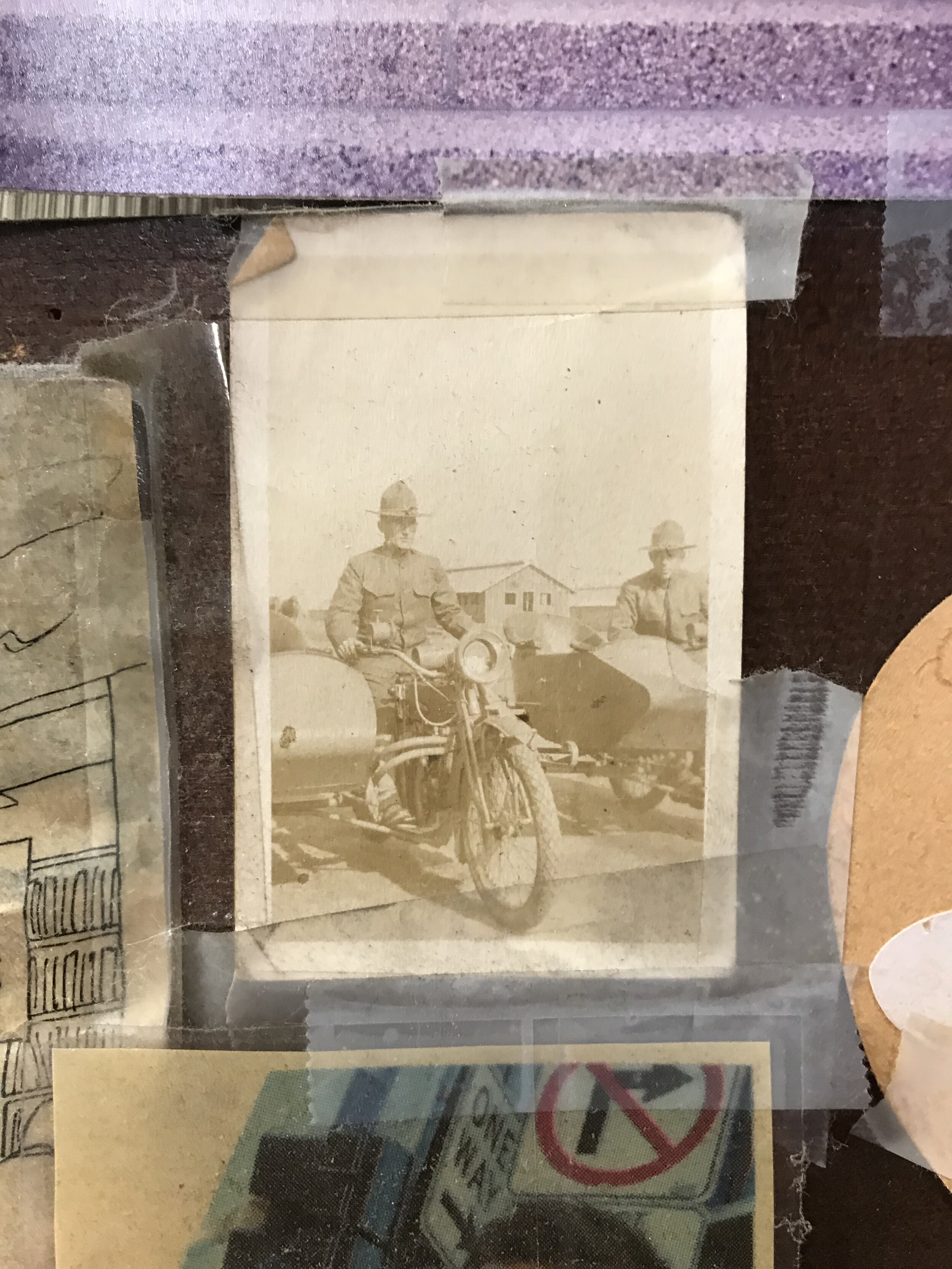

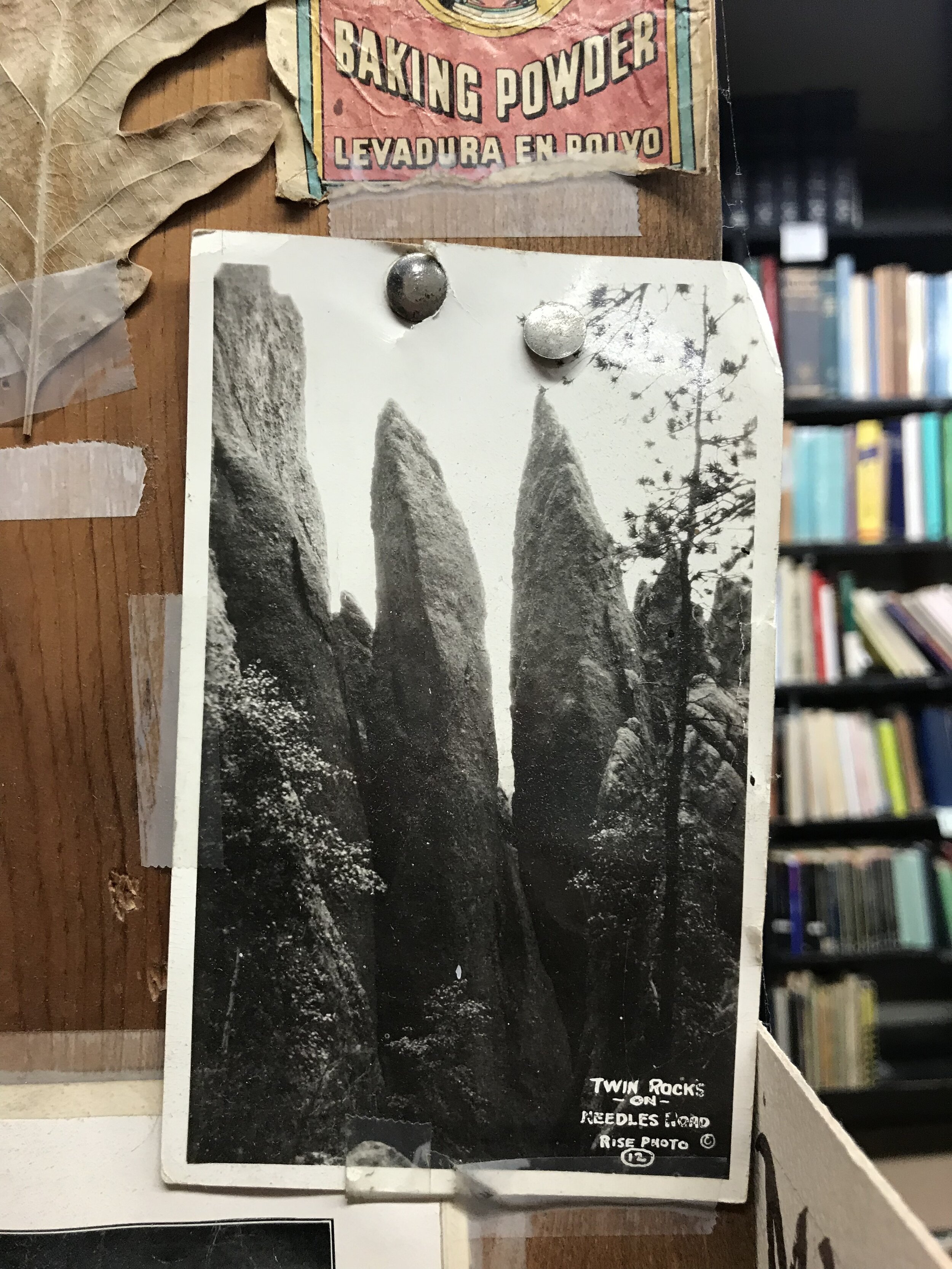

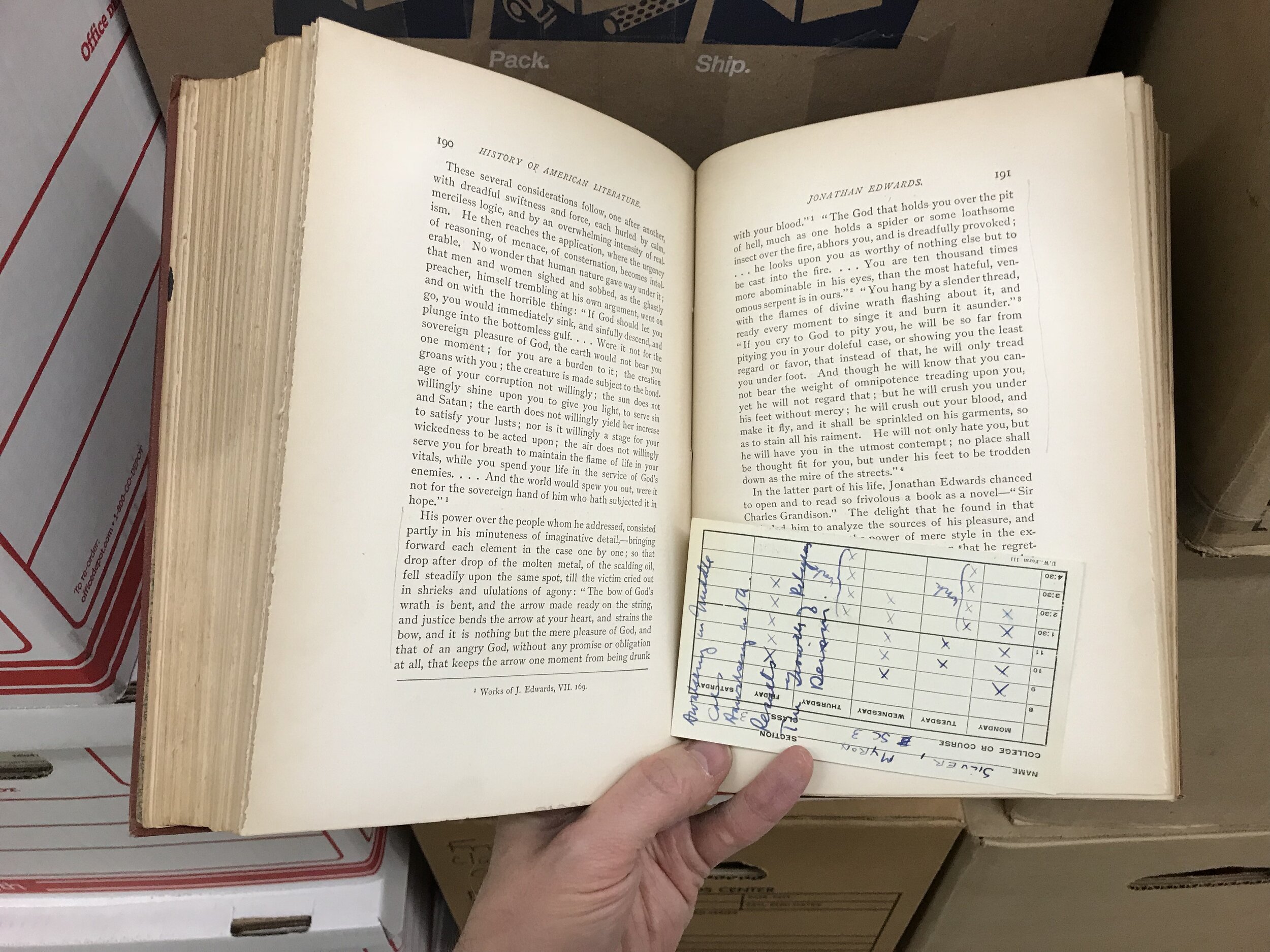

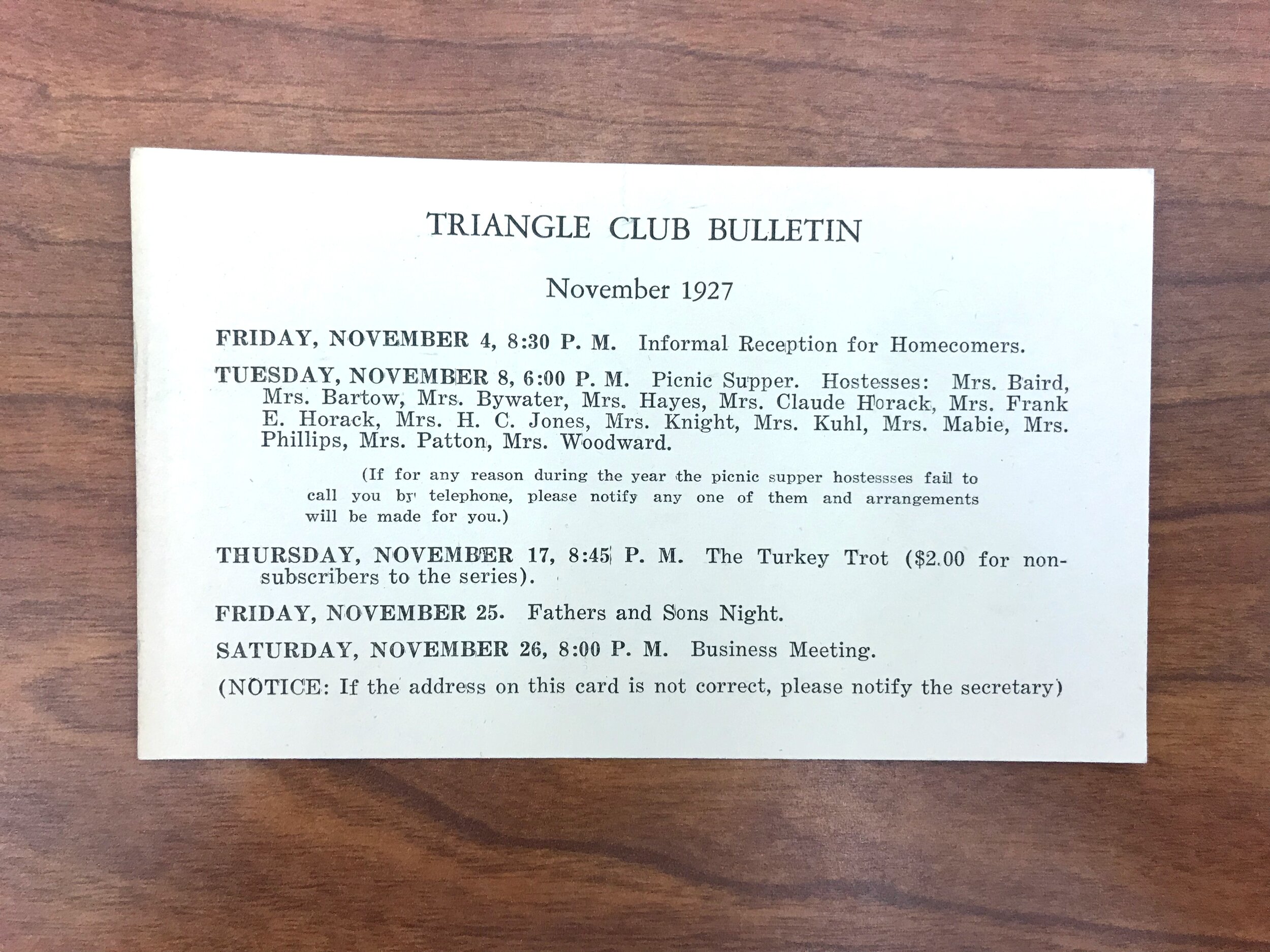

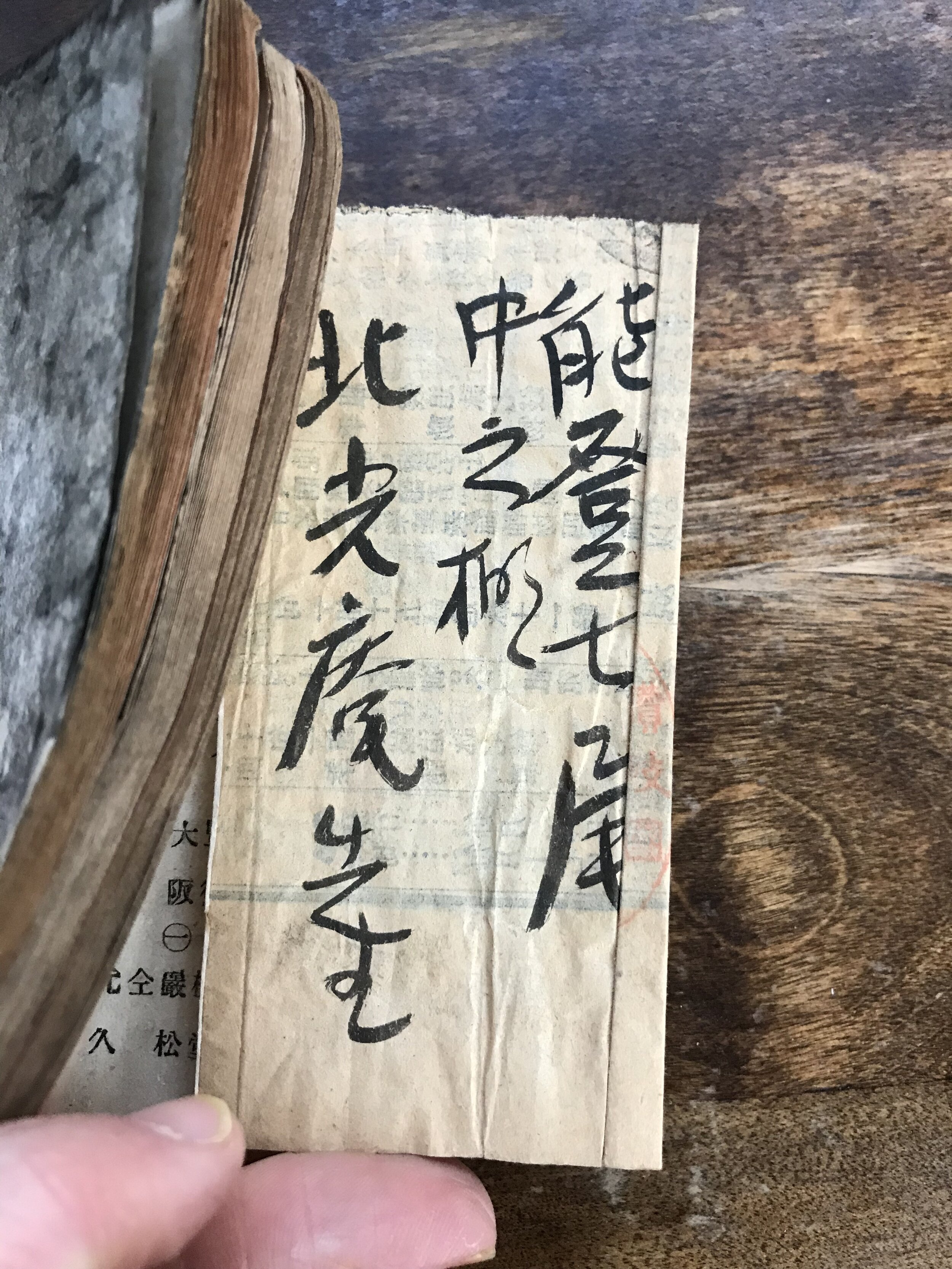

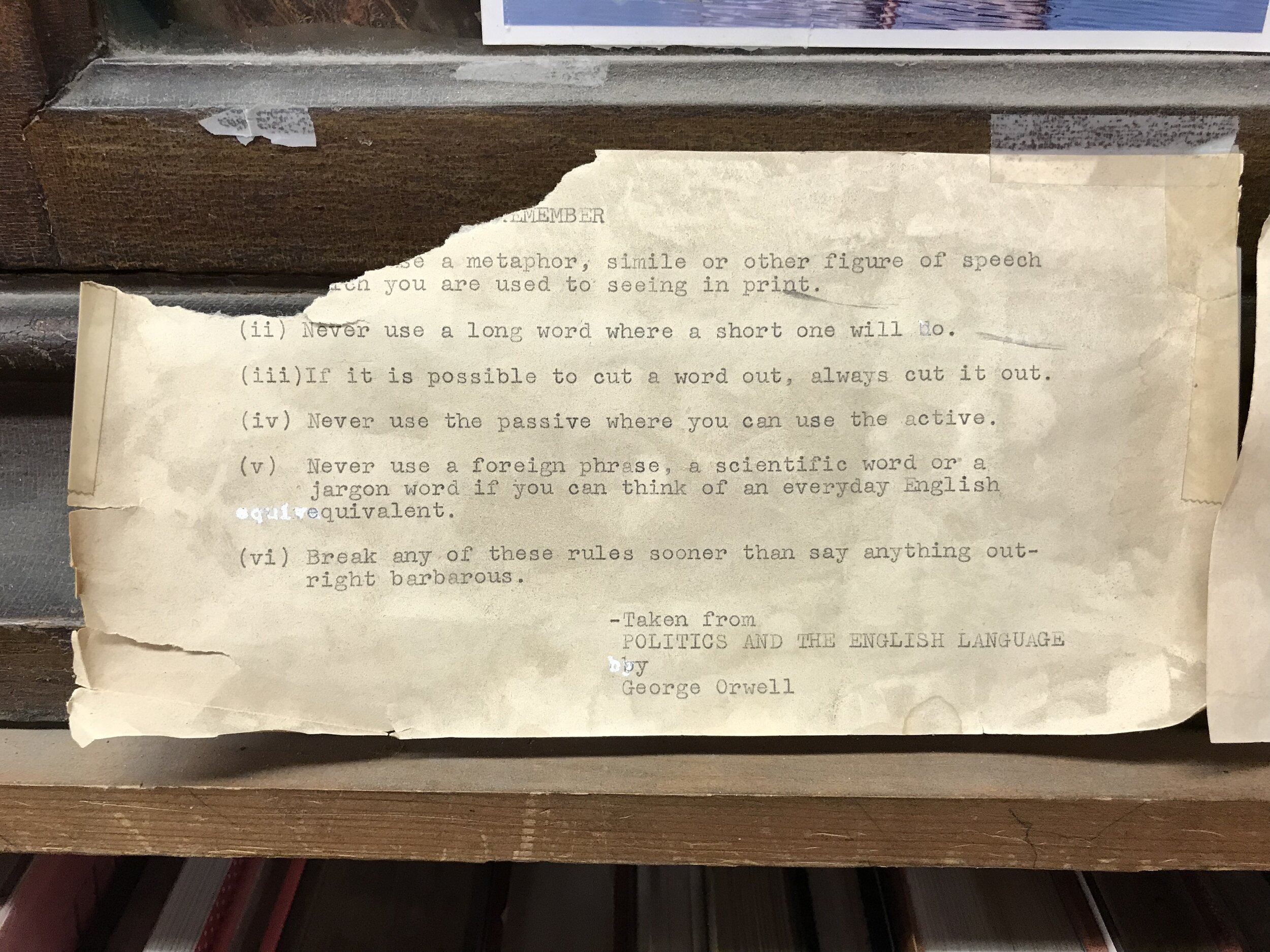

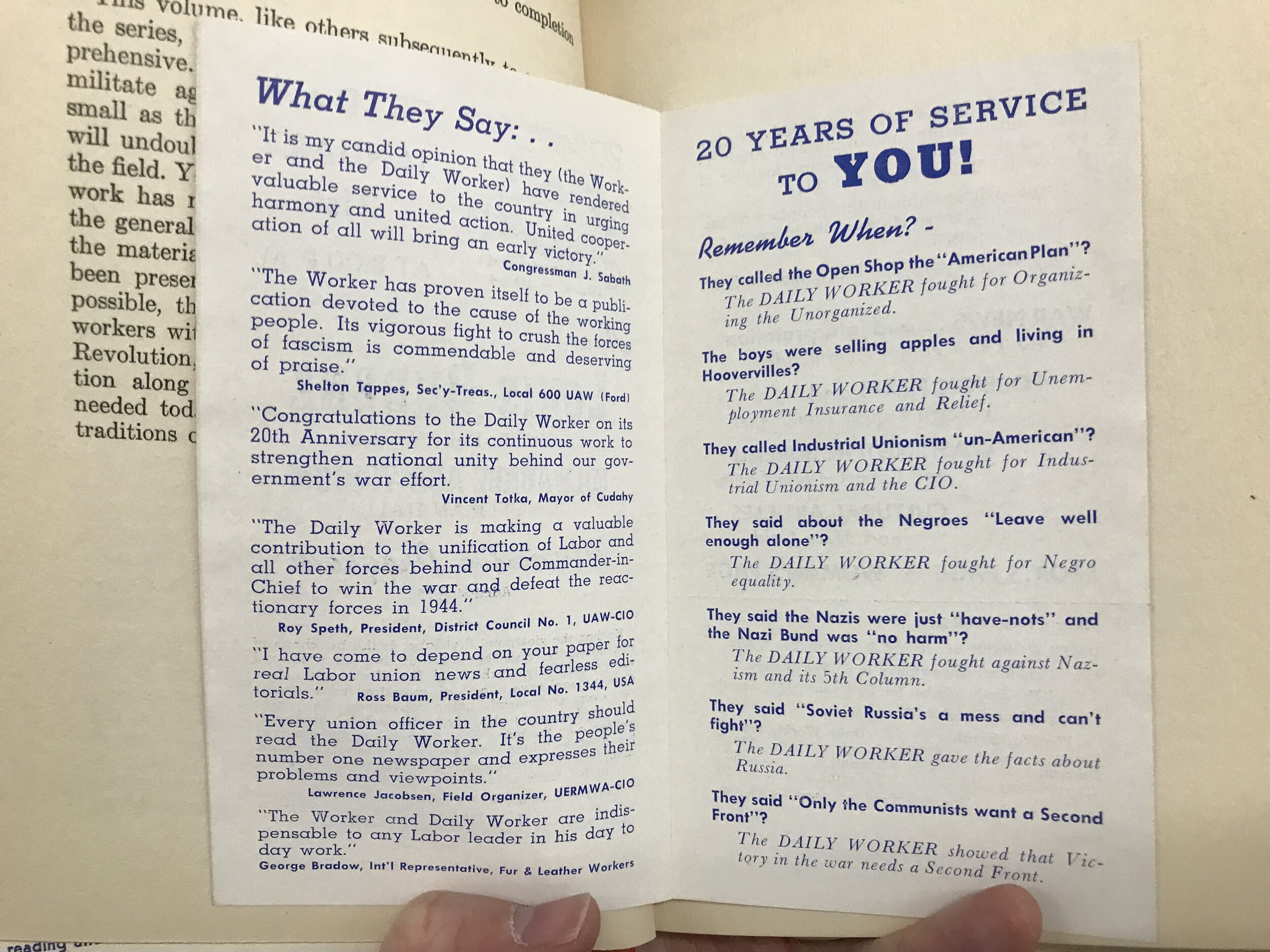

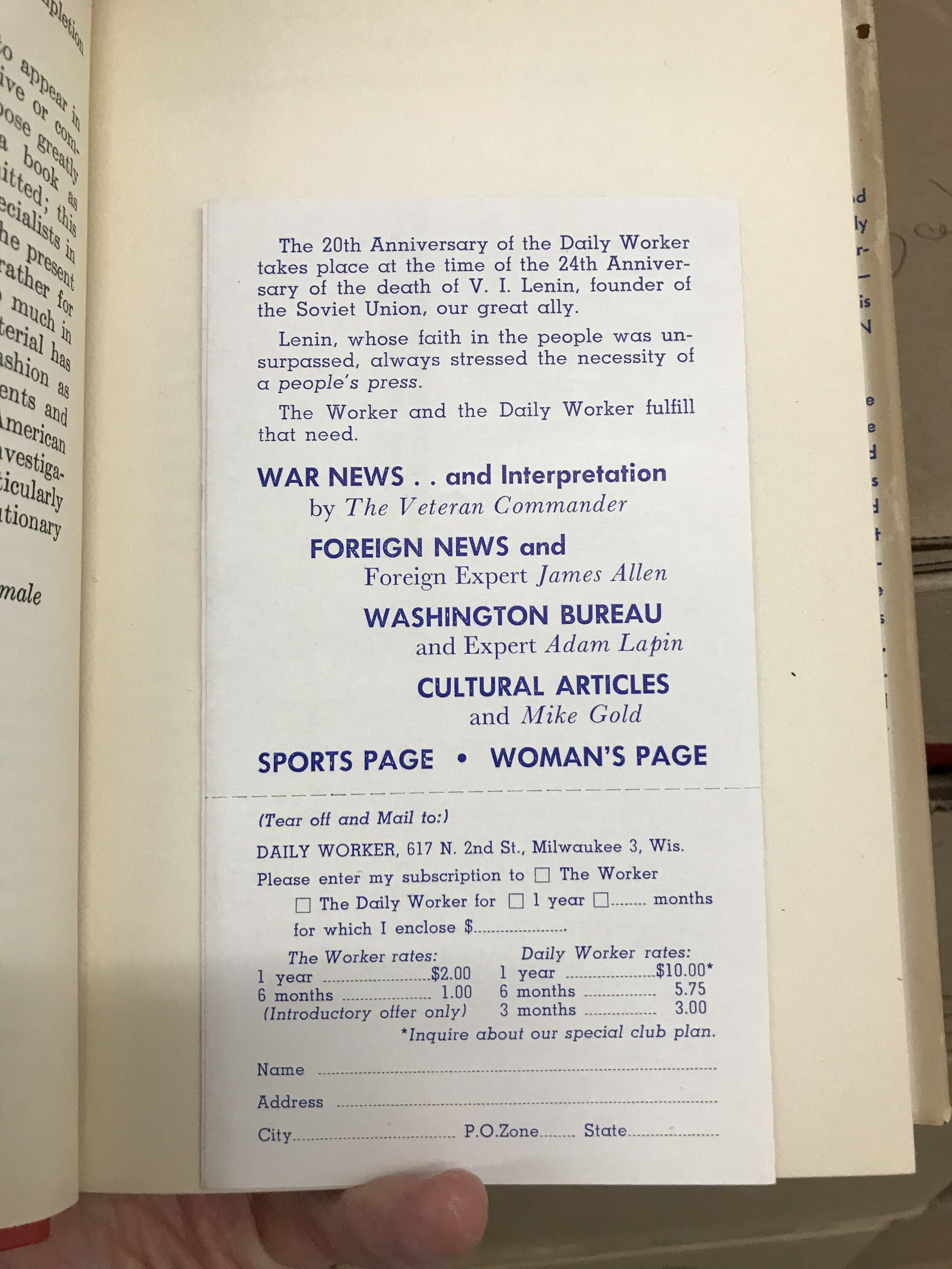

Enter human modifications, or the additions users give to a book after it leaves the production line. These modifications come in many different forms and can be intentional or unintentional. I speak of bookplates, inscriptions, notes, underlining, highlighting, stains, oils, and more. Users of a book, unwittingly or not, “remake the book,” using the words of book scholar Leah Price. A book's text and content can bring us into an imagined and illustrated world, as orchestrated by the author; but the book’s modifications can bring us into the "real," material world and all the people, events, and worlds it entails.

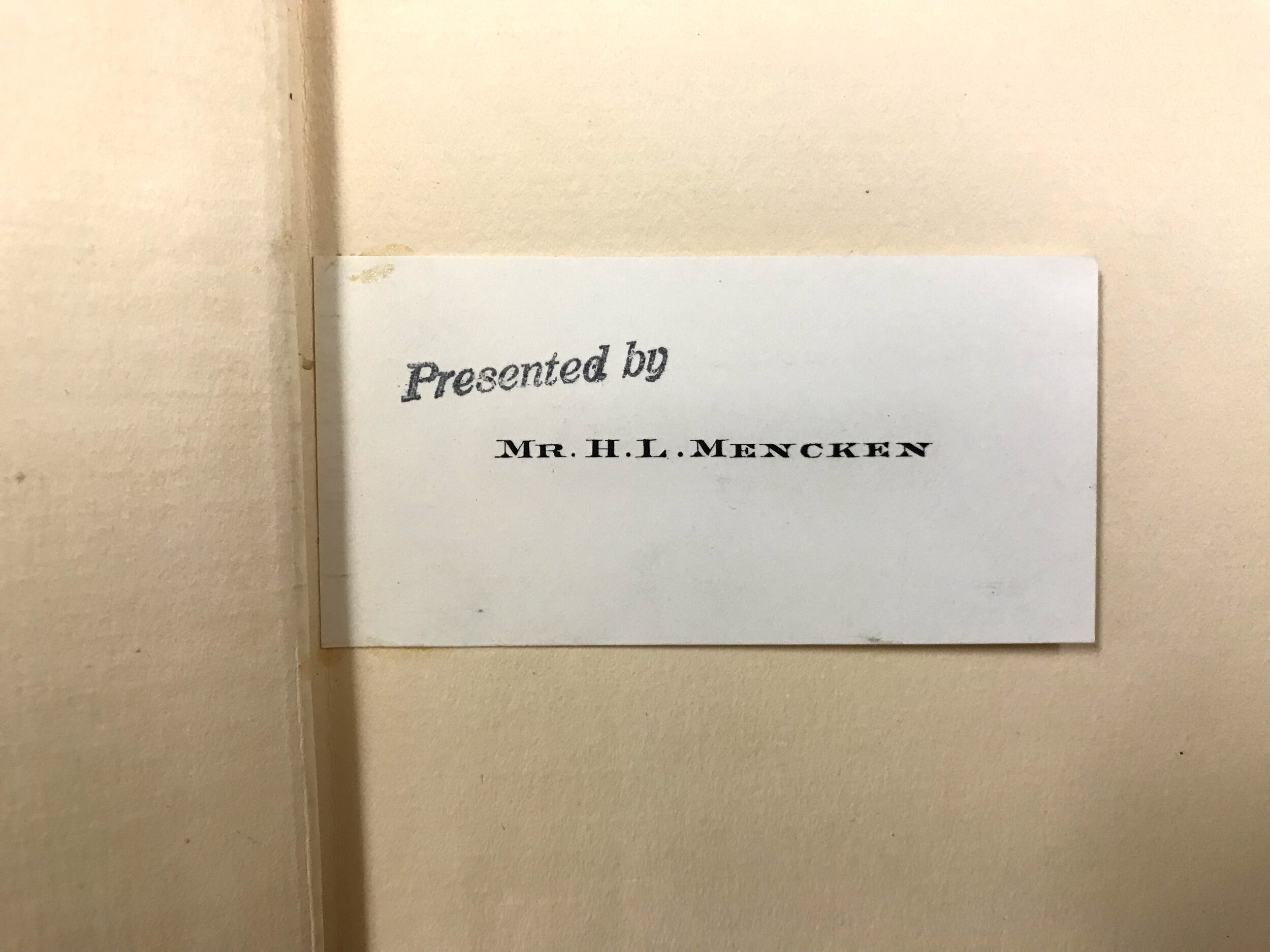

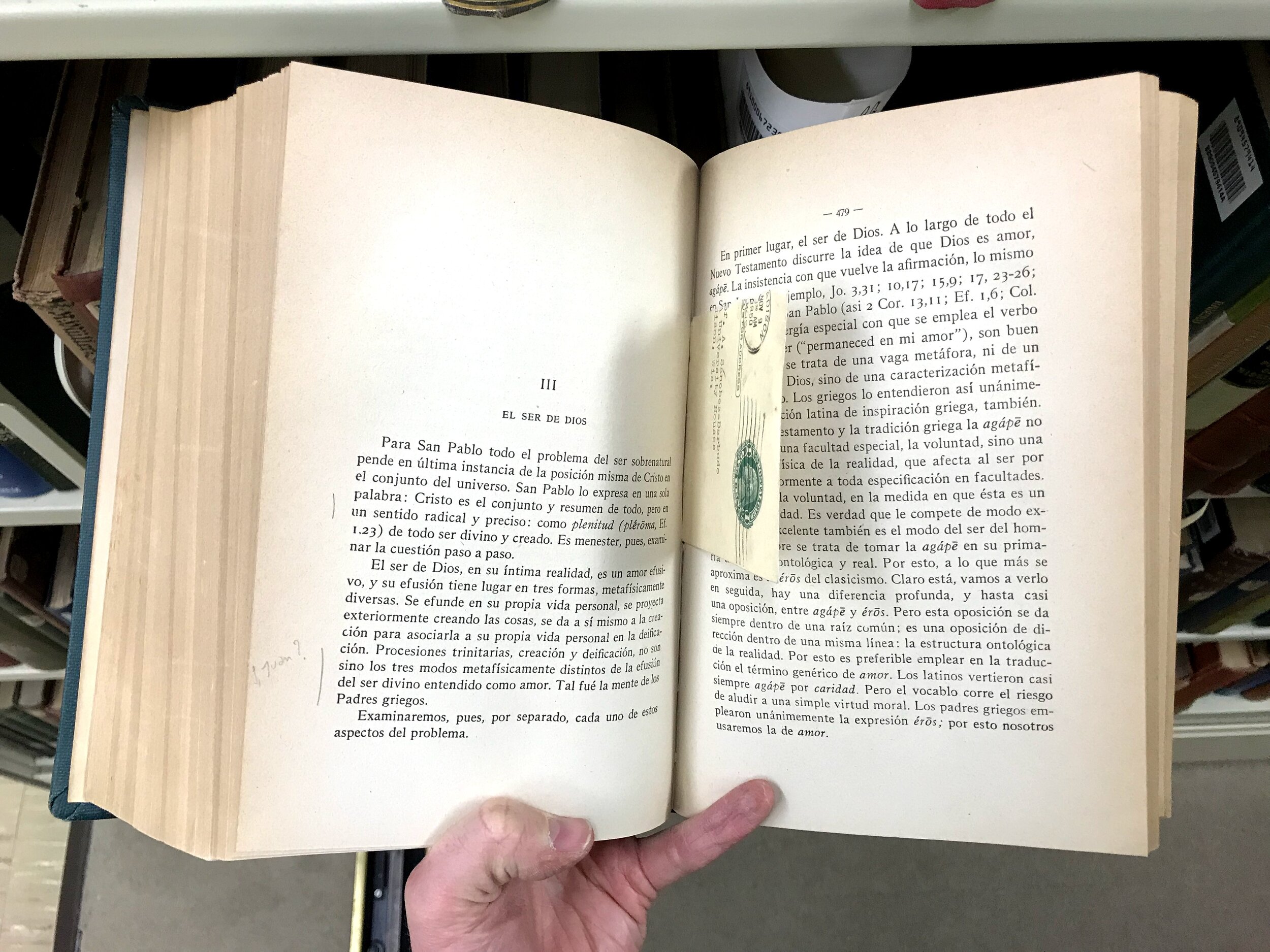

A found bookplate from UW’s Memorial Library

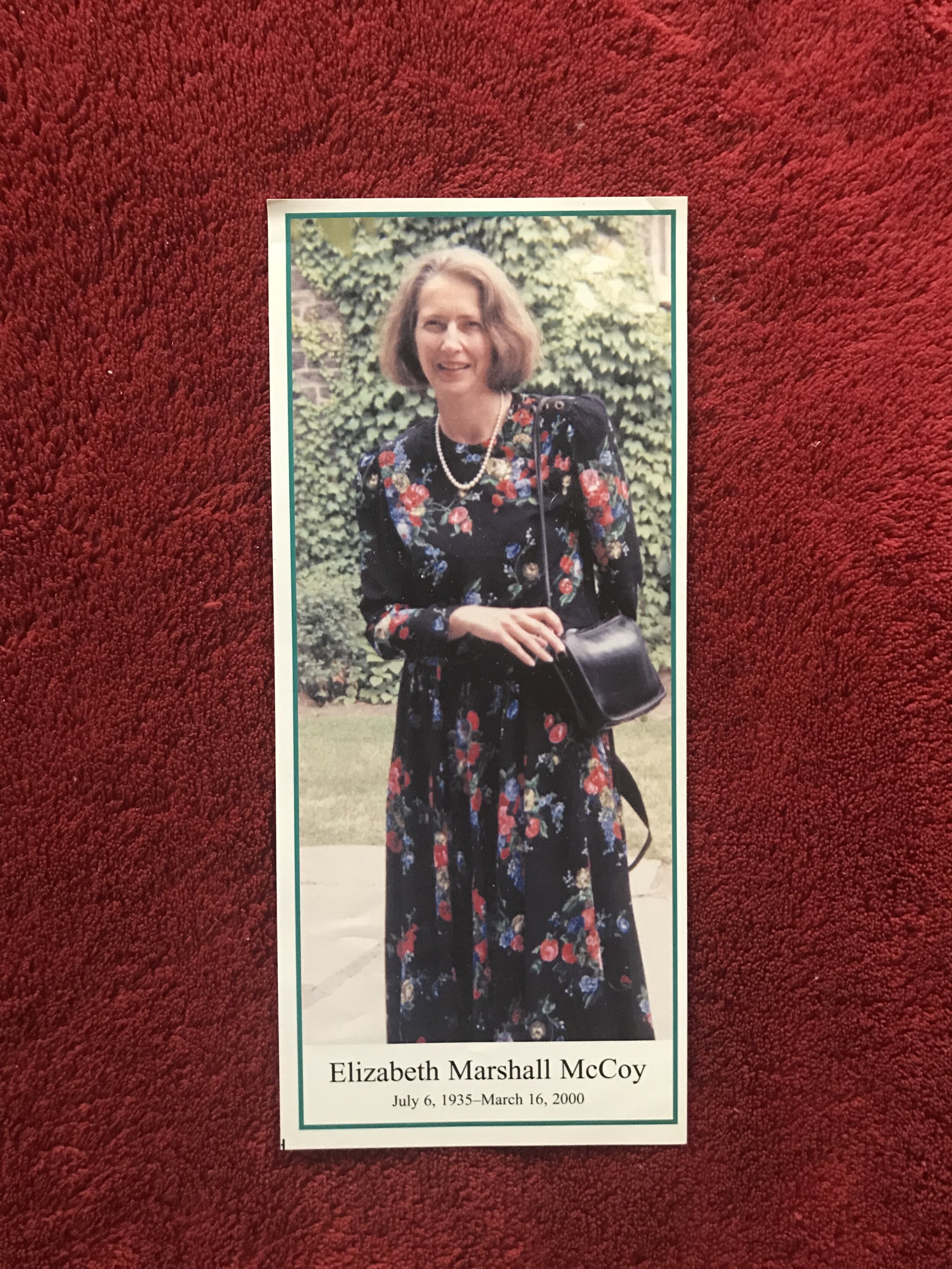

There, too, is an imaginary world hinted at by these modifications, albeit not crafted by the author but implied and deduced by us when we encounter previous users’ traces. Looking at a modification such as an ex-libris bookplate, we grasp for more information and our imaginations often fill in the blanks. Who was this person? What did they do? Why did they choose this image to represent them? Where did they live? And, of course, is this a trace of someone now gone? These questions, a result of a previous “real human” intervention, causes our minds to create a new, imaginary plane, one outside of what most of us would traditionally refer to as the book’s content.

*Price continues to explain that the standardization would later spread to medicine and nearly “everything else."

**While I speak of the “Western tradition” it is important to note that it did not exist in isolation; many scholars have written at length about the “outside” influences on Western print culture. For an excellent introduction, please read chapter 5, “The Invention and Spread of Printing” in History of the Book, Johanna Drucker’s freely available course guide.

III.

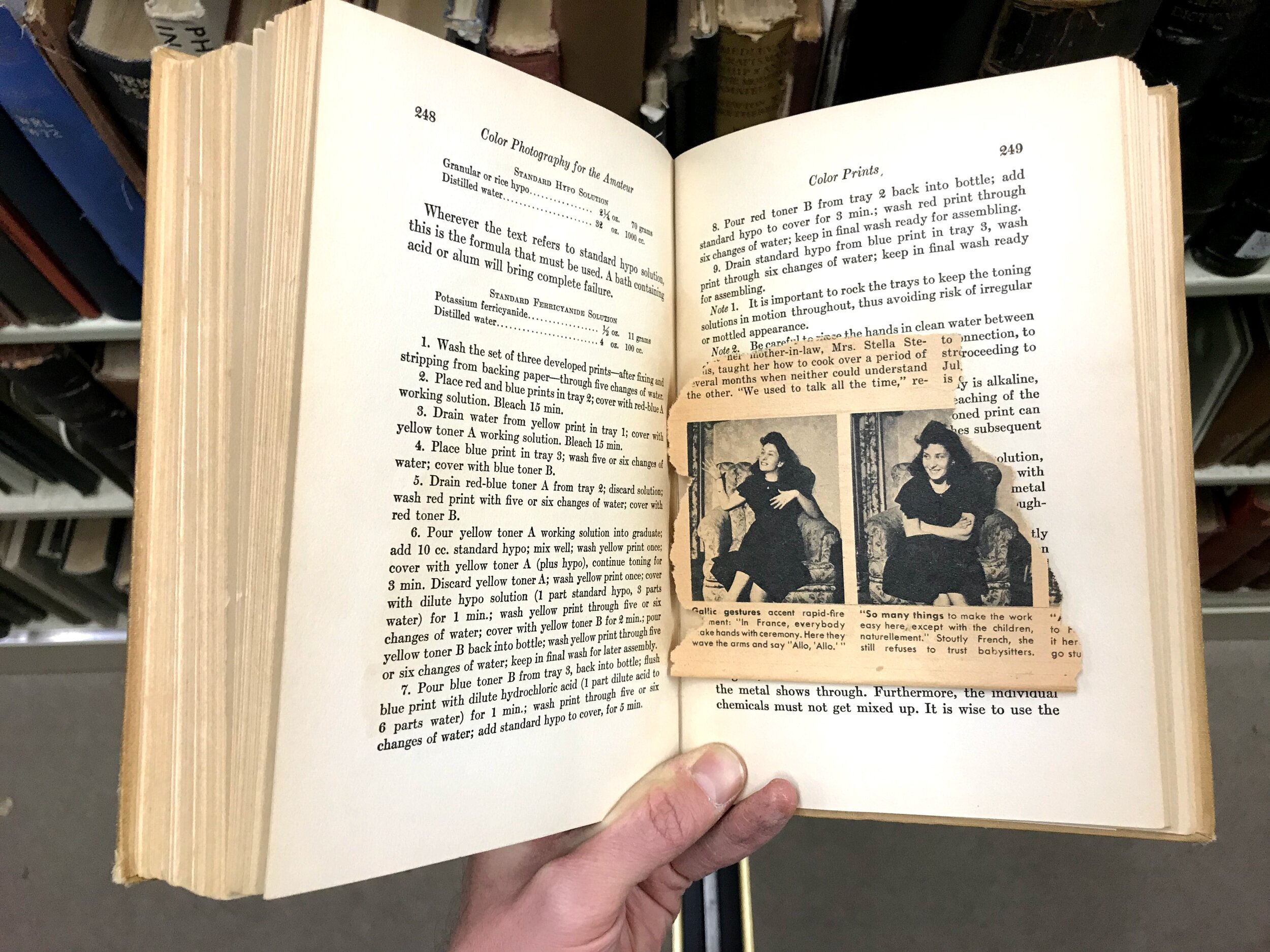

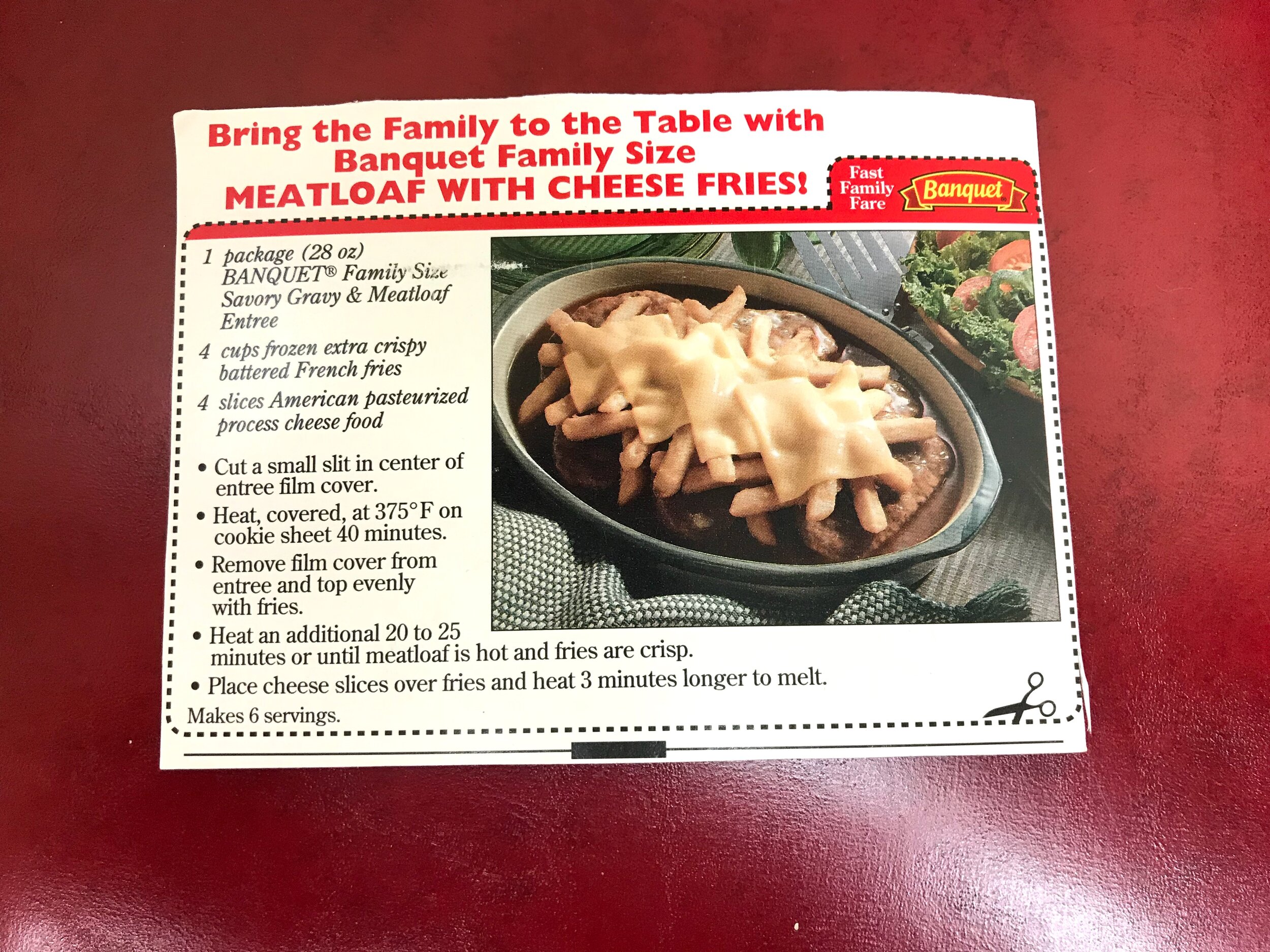

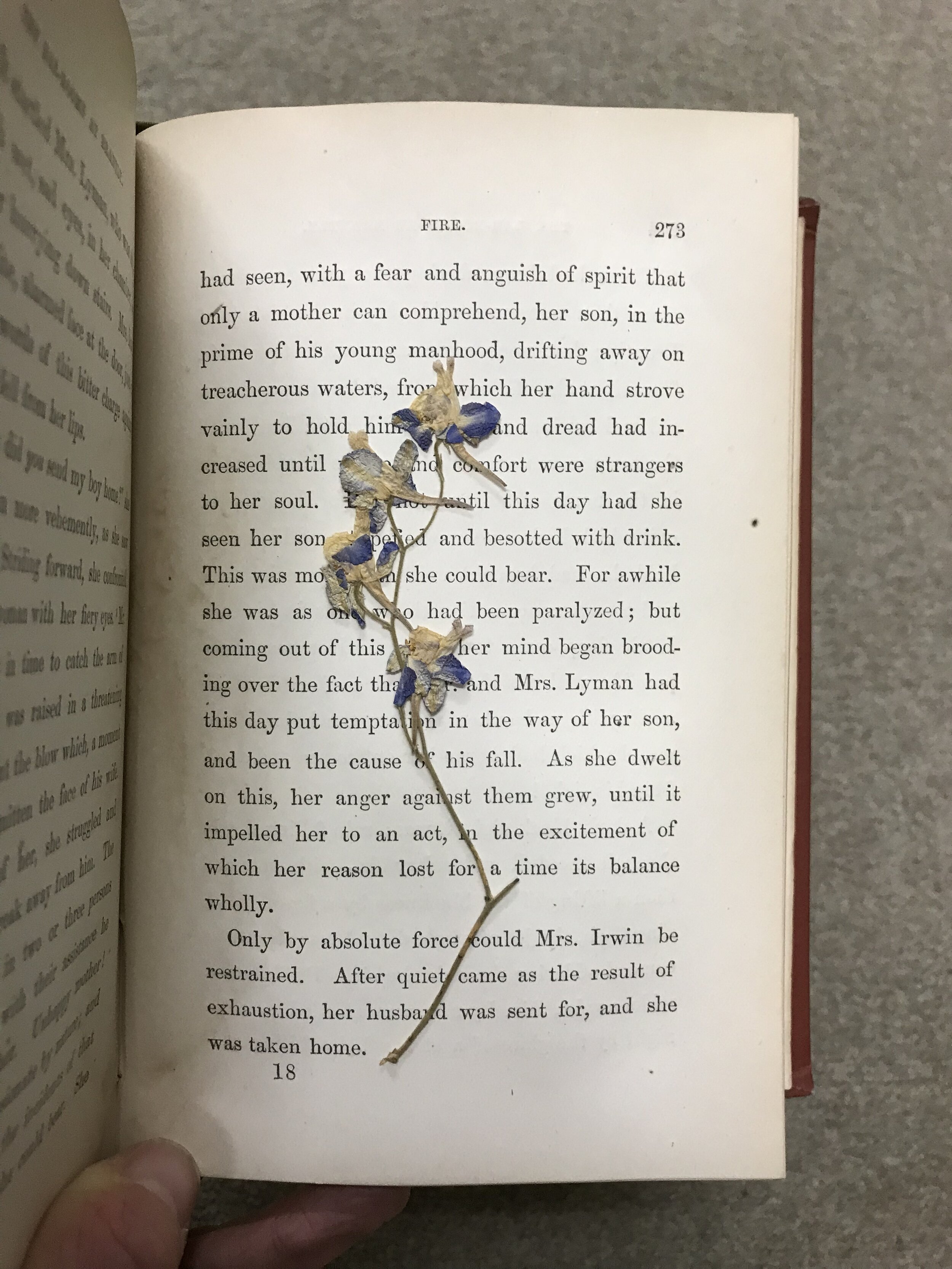

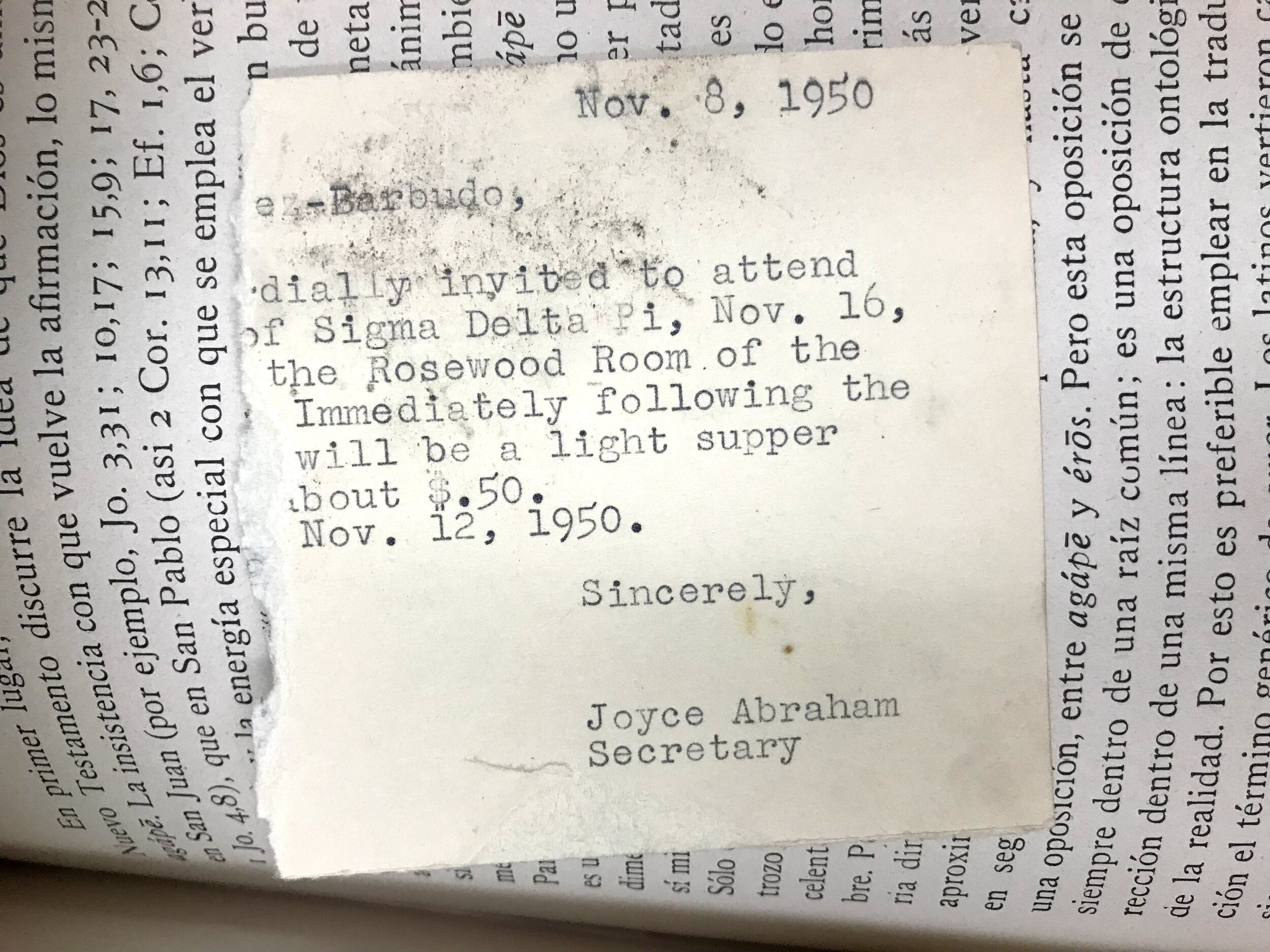

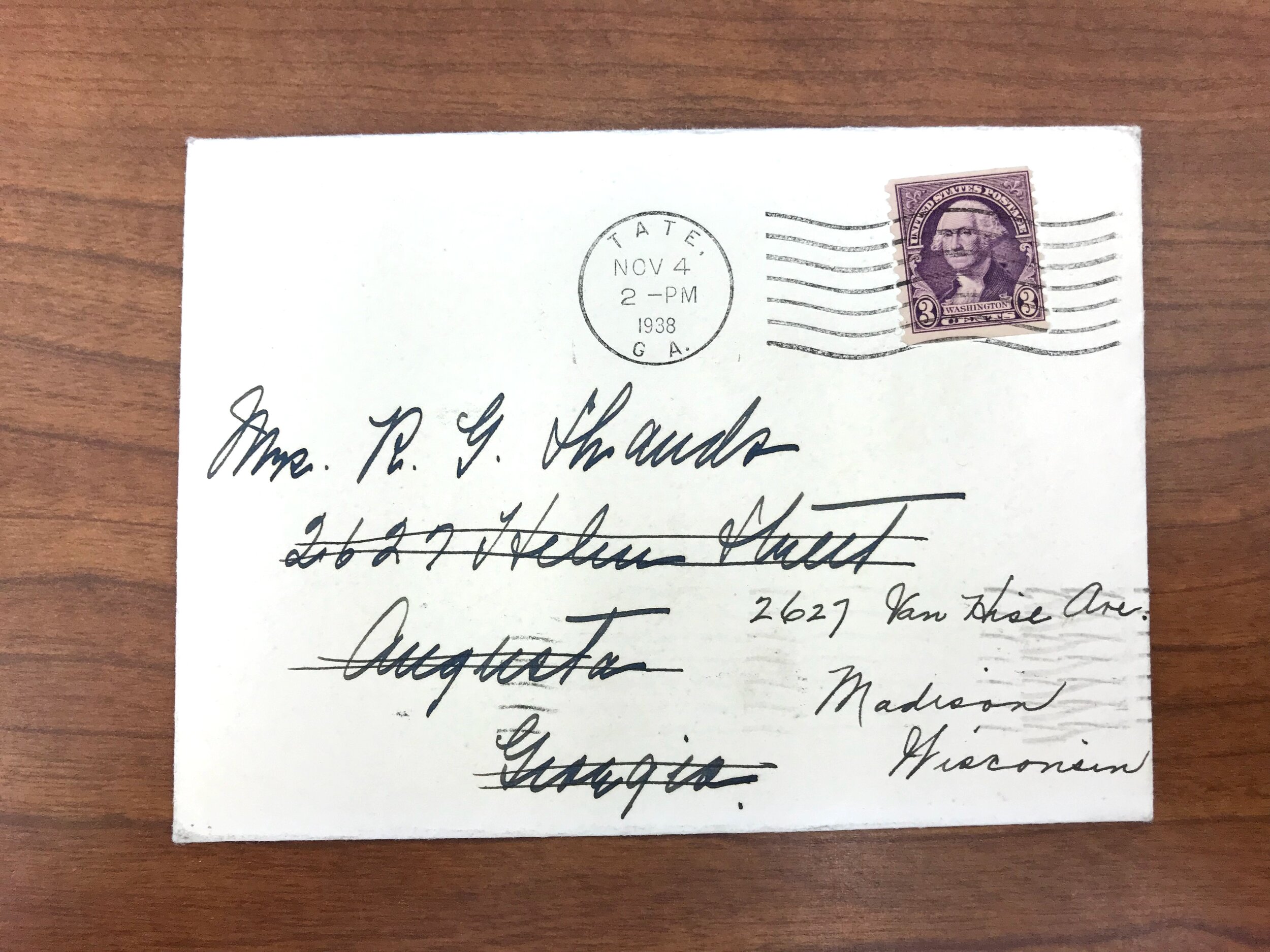

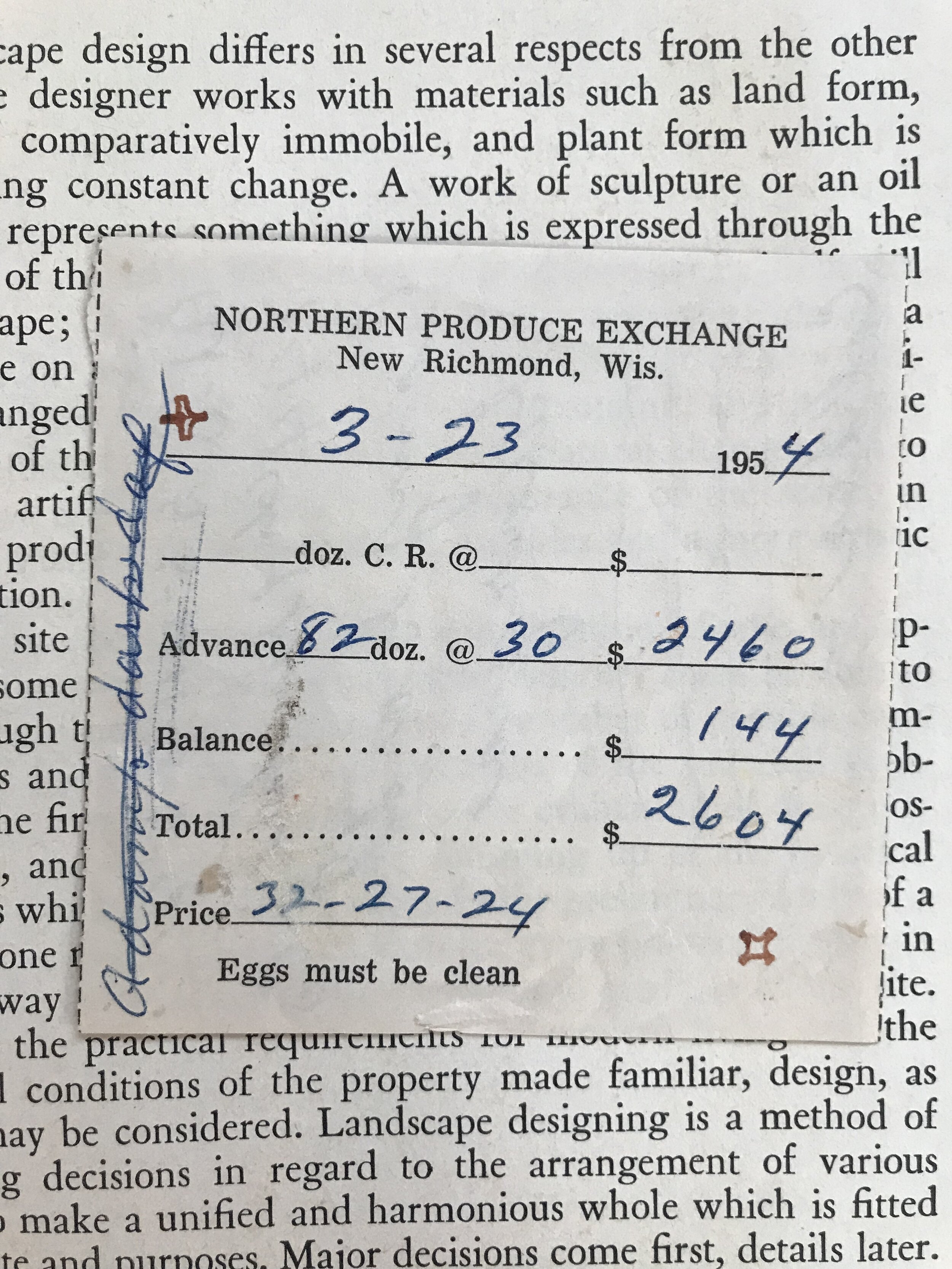

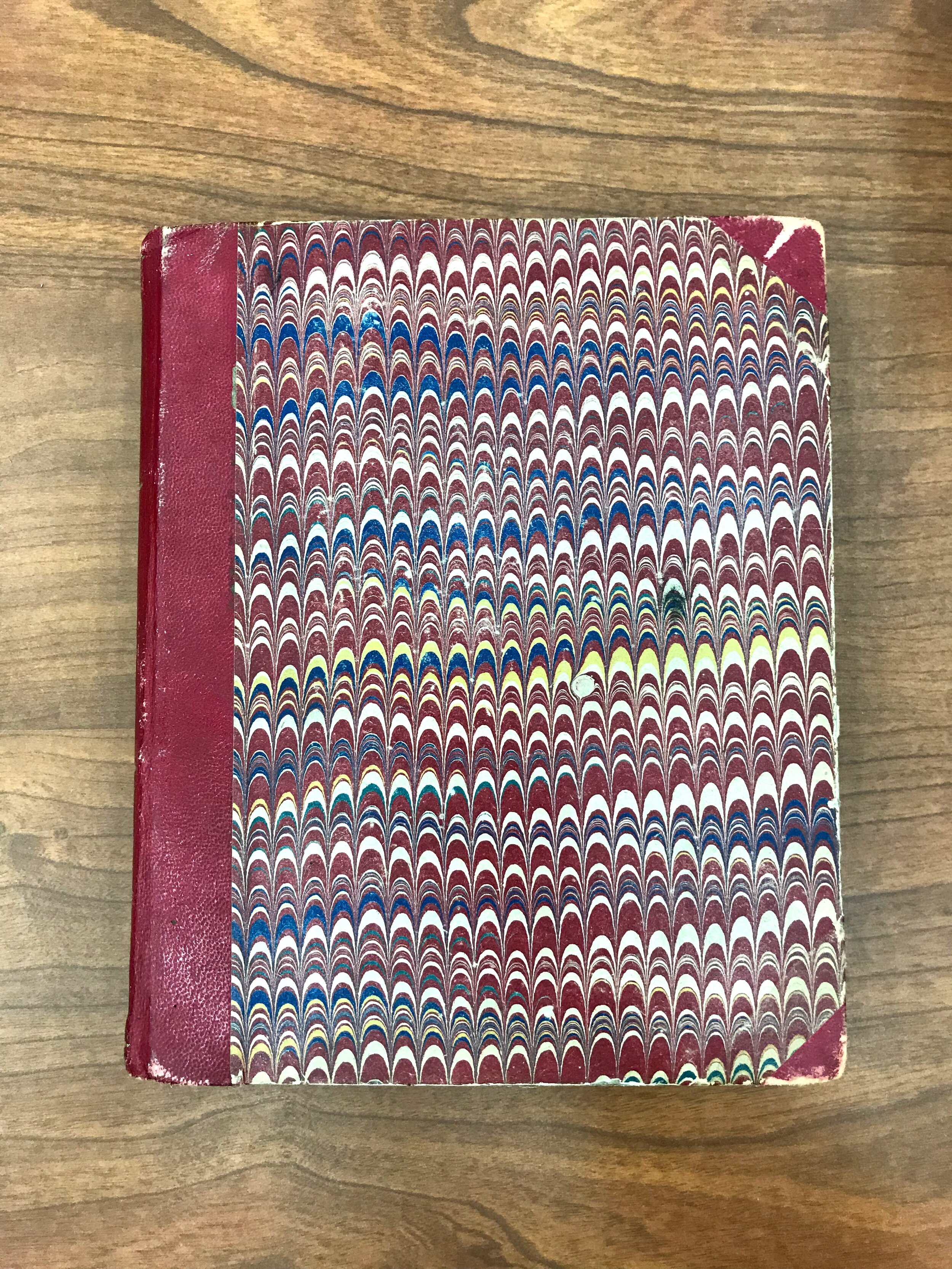

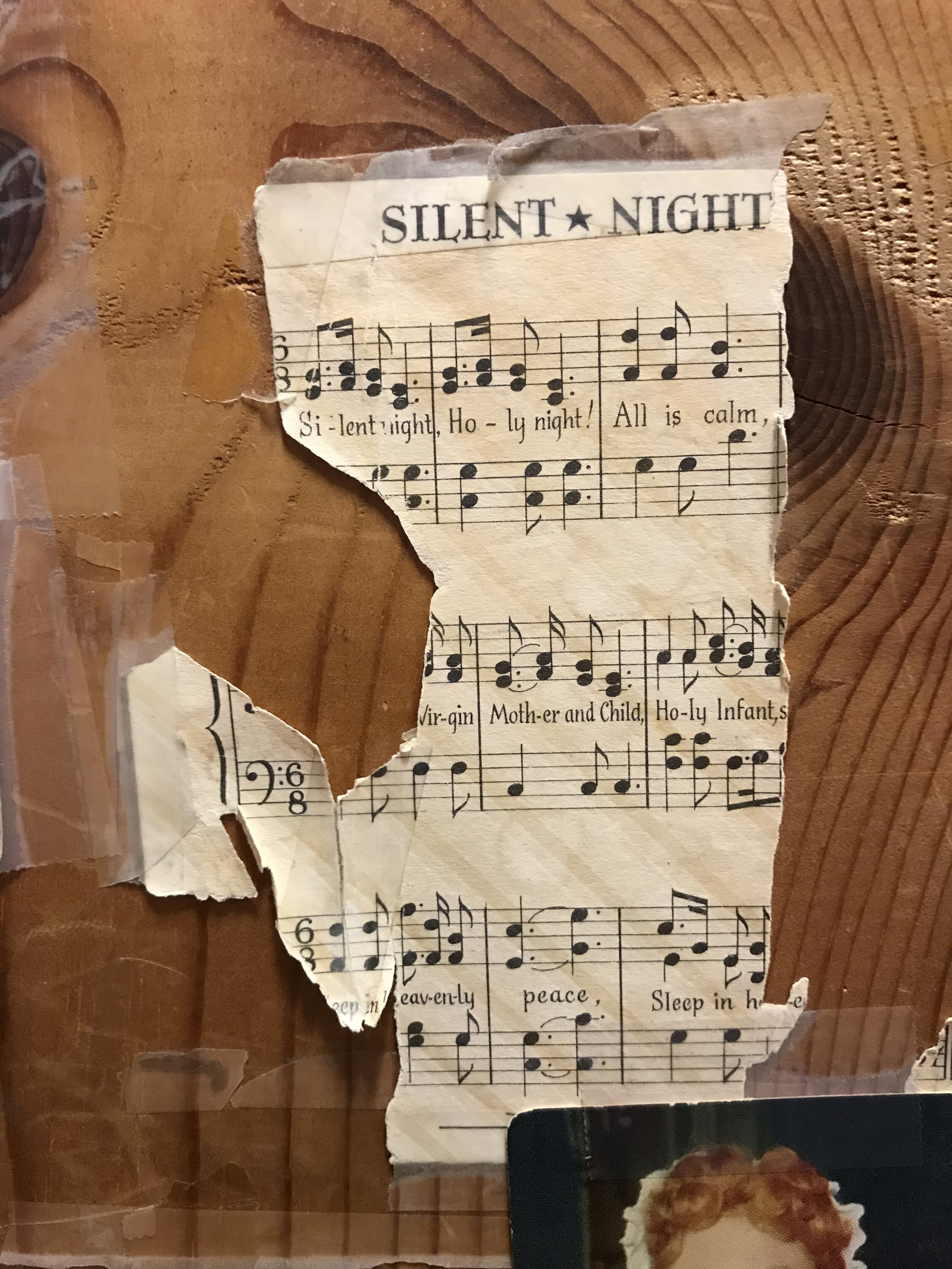

Interacting with the book as a reader, we disappear into the content crafted by the creator; encountering the book as a bibliographer, we become conscious of the community who has produced the book. Modifications bring us even closer to the community of users who have handled the book after its initial dissemination; they remake the book and underscore its uniqueness. Yet, sometimes, as you are reading a book, you come across something tucked in between its two covers: a love letter, a concert ticket, a photograph. The ephemera, or insertions, as I will call them, transports us from the book, into the lives of its owners, and maybe more significantly, into the world outside of the text. Finding a flower can awaken you from the pervasive illusion that the book is merely a vessel for the author’s content. When you find a recipe for a casserole in between chapters 10 and 11 of an epistemological study, the book's uniqueness (and the world in which it exists) is suddenly revealed.

So take what remains of this essay as it is; a playful and preliminary exploration of that world suggested by the pressed flower; a deeper look into how my friends, colleagues, and I have experienced the moment when we find some thing stored in a book.

IV.

As a book collector, I have often found insertions in books and feel a momentary and gentle jolt of a dimensional change; in time, place, and role. Too gentle of a jolt it seems, since my experiences, like the insertions themselves, often are lost and forgotten into the peripheries of life.

Yet the opportunity to investigate these insertions resurfaced when my professor for History of Books and Print Culture offered a generous interpretation for what our final term “paper” could be. I asked if investigating “stuff stored in books” was an appropriate project. The answer? A hearty affirmative, “Just as long as you are doing something you care about.”

My initial investigations started at the University of Wisconsin Library where I checked what scholarship was already available on book-stored ephemera. I was able to find surprisingly little.* On an academic level, Book Traces, based at the University of Virginia, seemed to be one of the only places where this ephemera is systematically cataloged and highlighted on an institutional level (I would later discover many institutions, my own University of Wisconsin included, sometimes recorded instances of insertions but never collected them into one resource). Of printed books, too, there was little available; most notable were Ander Monson’s Letter to a Future Lover: Marginalia, Errata, Secrets, Inscriptions, and Other Ephemera Found in Libraries and Michael Popek’s Forgotten Bookmarks: A Bookseller's Collection of Odd Things Lost Between the Pages.

Yet, of course, a less scholarly approach on the world wide web yielded significantly more results. Behind these results were more people like me, infatuated, mystified, and interested enough with items that they had found that they wanted to show the world.

For instance:

From “The UBC Find of the Week” blog, hosted by the Brookline Booksmith:

From Abebooks.com:

“Be careful what you use as a bookmark. Thousands of dollars, a Christmas card signed by Frank Baum, a Mickey Mantle rookie baseball card, a marriage certificate from 1879, a baby’s tooth, a diamond ring and a handwritten poem by Irish writer Katharine Tynan Hickson are just some of the stranger objects discovered inside books by AbeBooks.com booksellers.”

-Abebooks.com

From Twitter:

Other notable items found? Human effluvium, a Polaroid of a cat wearing a leather mask, cockroaches, suicide notes, $1000 bills, bacon. You know, the usual.

Having found a community and some foundational material, it was time for me to hit the books in search of treasure, connections, and history.

*While it is an intriguing area for further study, it’s important to consider that, in most cases, book-stored ephemera would be very difficult to authenticate and very easy to “forge.”

V.

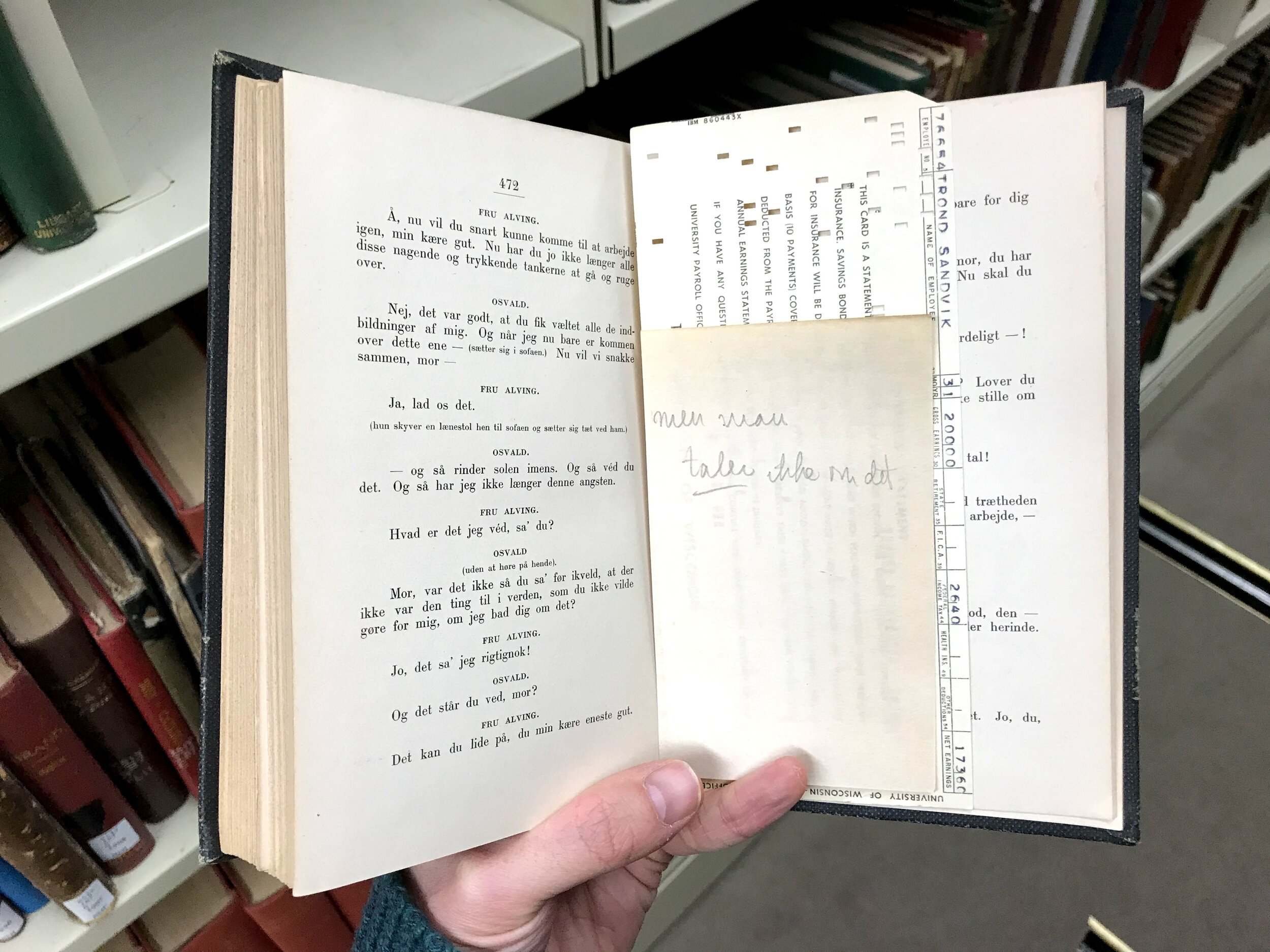

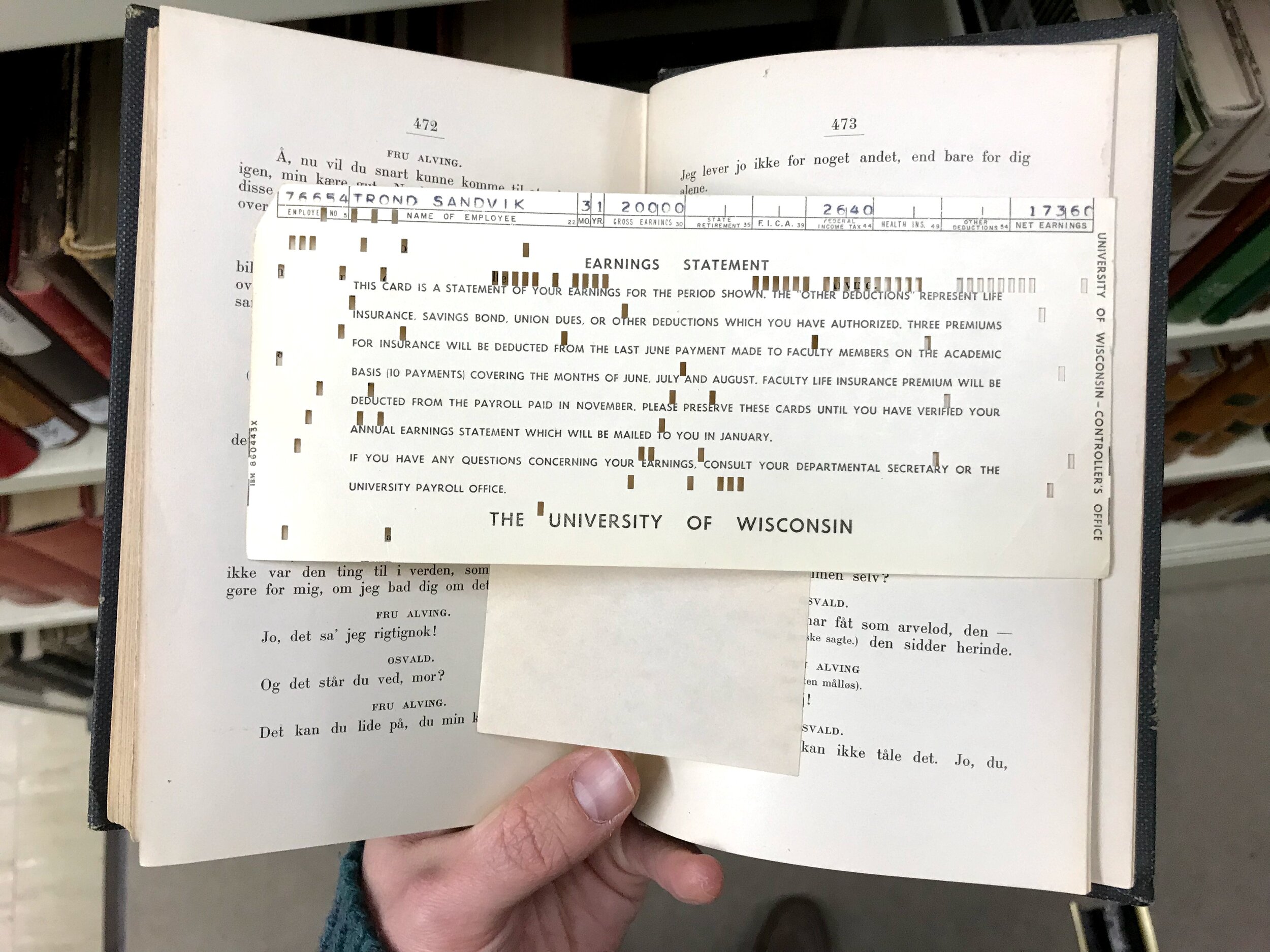

So I went to the stacks of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Memorial Library. Here I spent hours thumbing through books, looking for insertions. Before finding any treasure, I found I was allergic to some of the books’ involuntary modifications (mold, dust). While it made me very conscious of the book as a unique item, I also learned to point the books away from my face as I searched. After the first few hours, I became somewhat discouraged by the lack of ephemera I was finding. Yet, each time I came across a business card, a pay stub, or a bookmark, I kept digging like one searching for treasure. Not entirely indiscriminate, I honed in on the poetry and art books, encyclopedias, and reference books, hoping to find love letters, botanicals, or photos. My strategy was mostly disproven in my four search sessions; the majority of my finds came from scientific or historical books. Yet, over the course of my searches, I would find a substantial amount of material, some of which you will see in the galleries below.

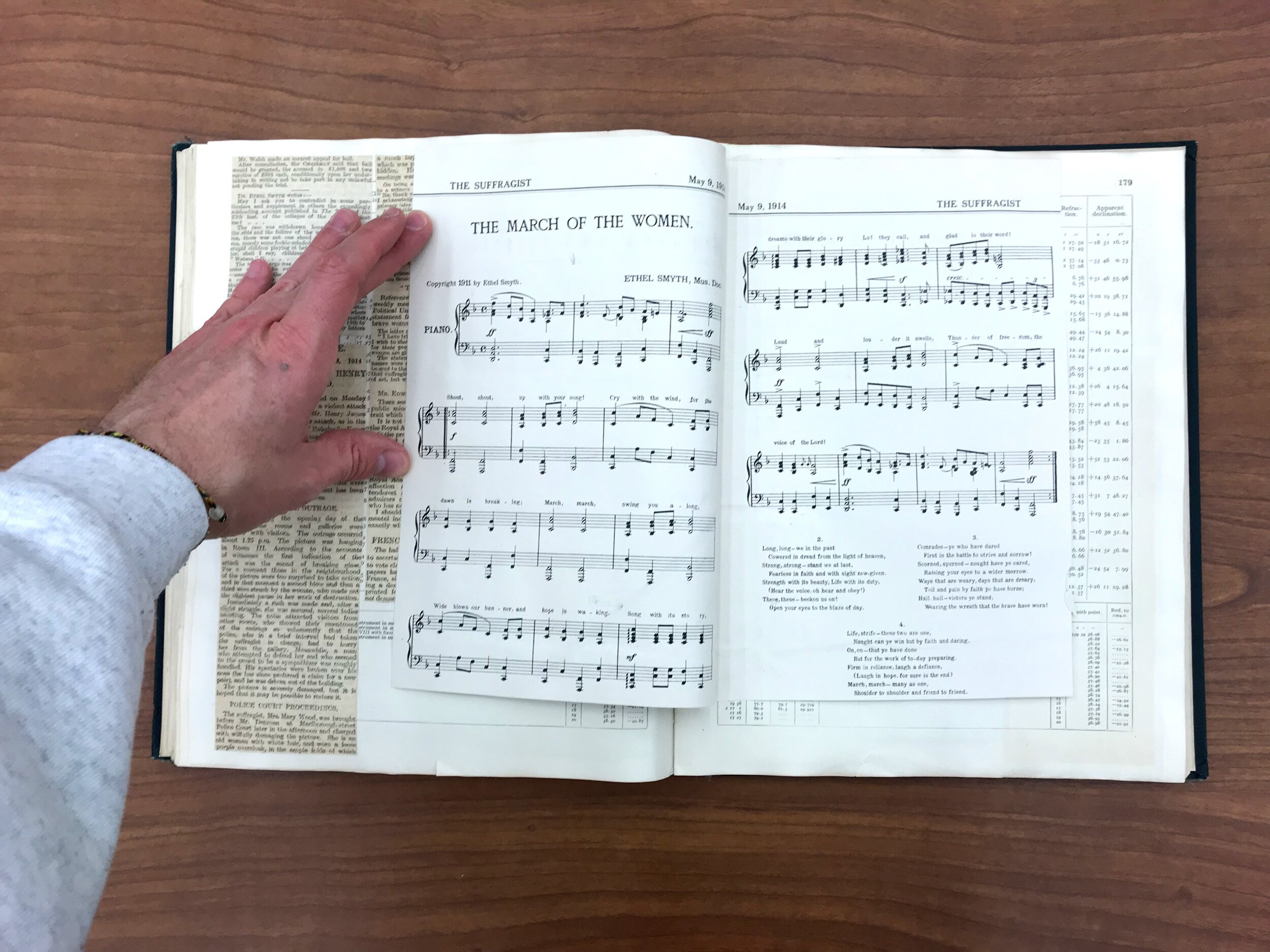

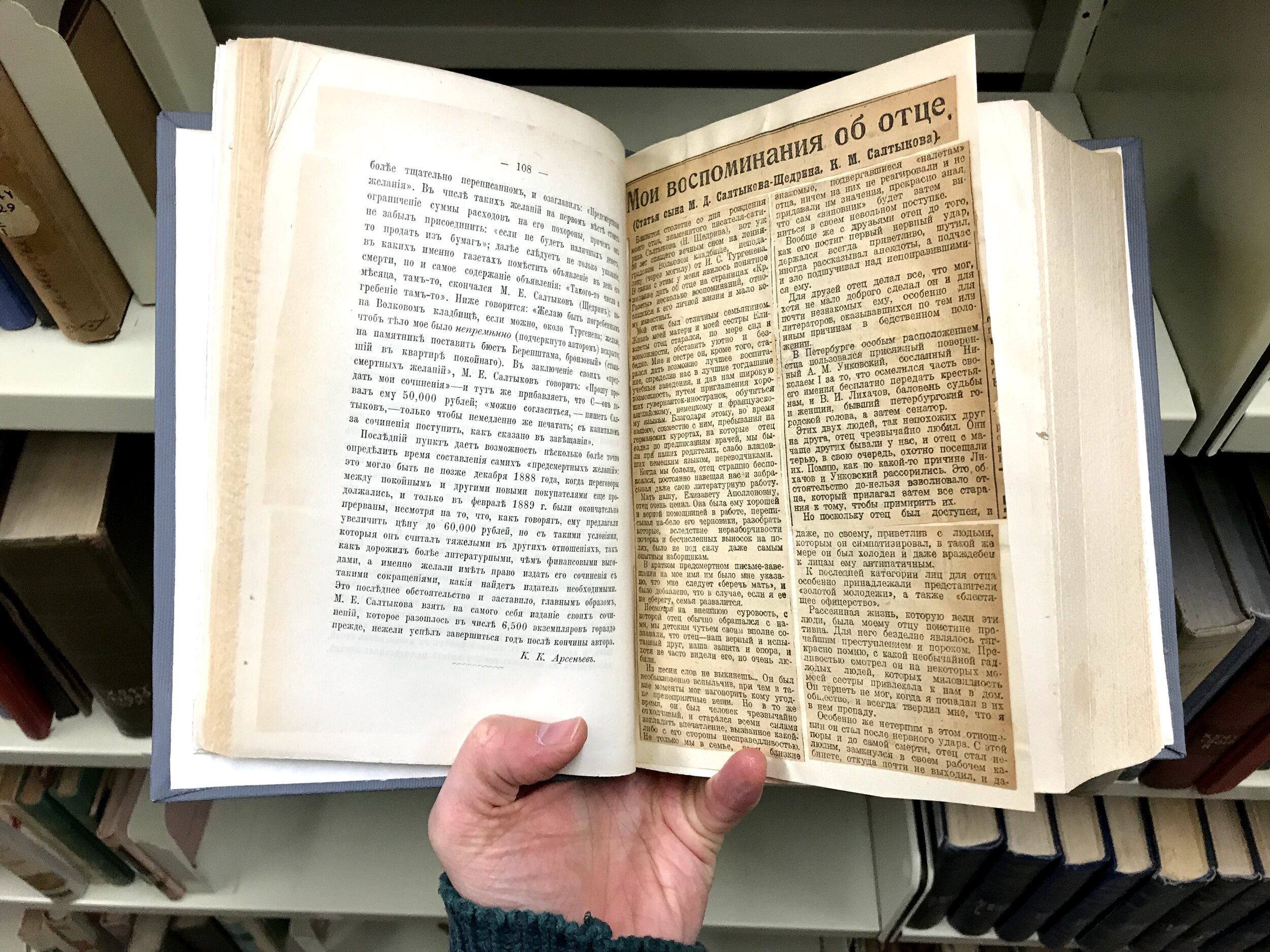

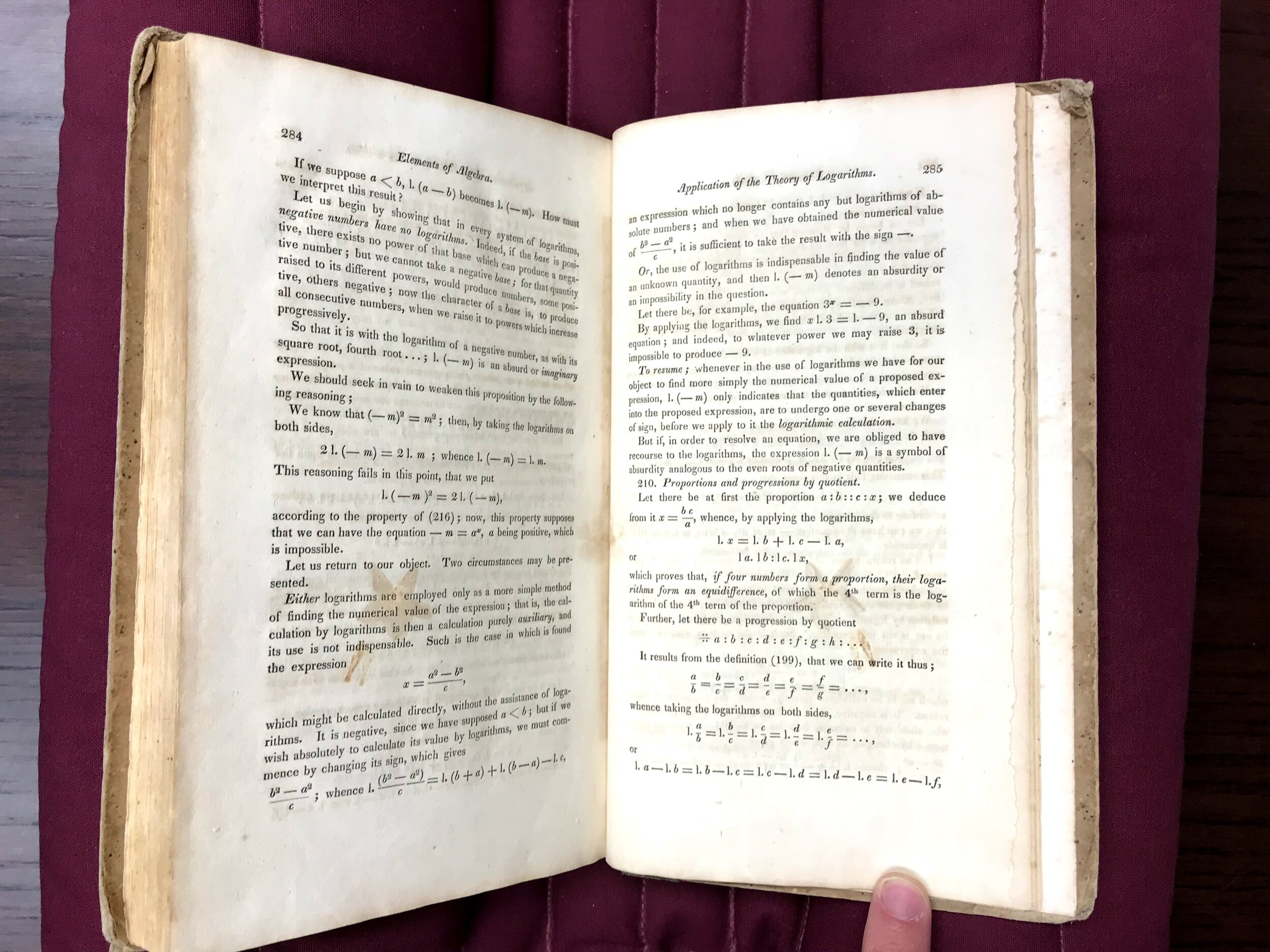

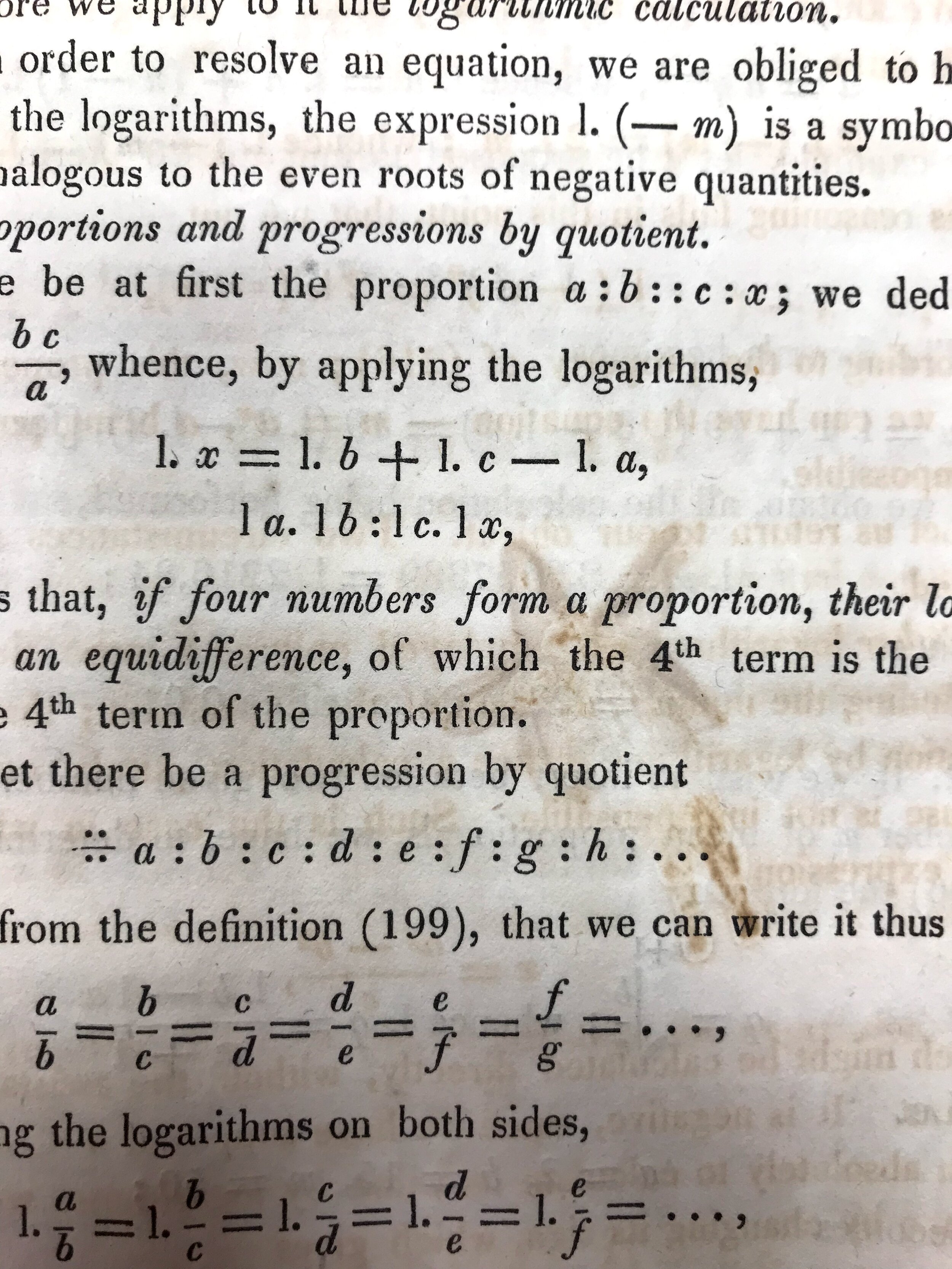

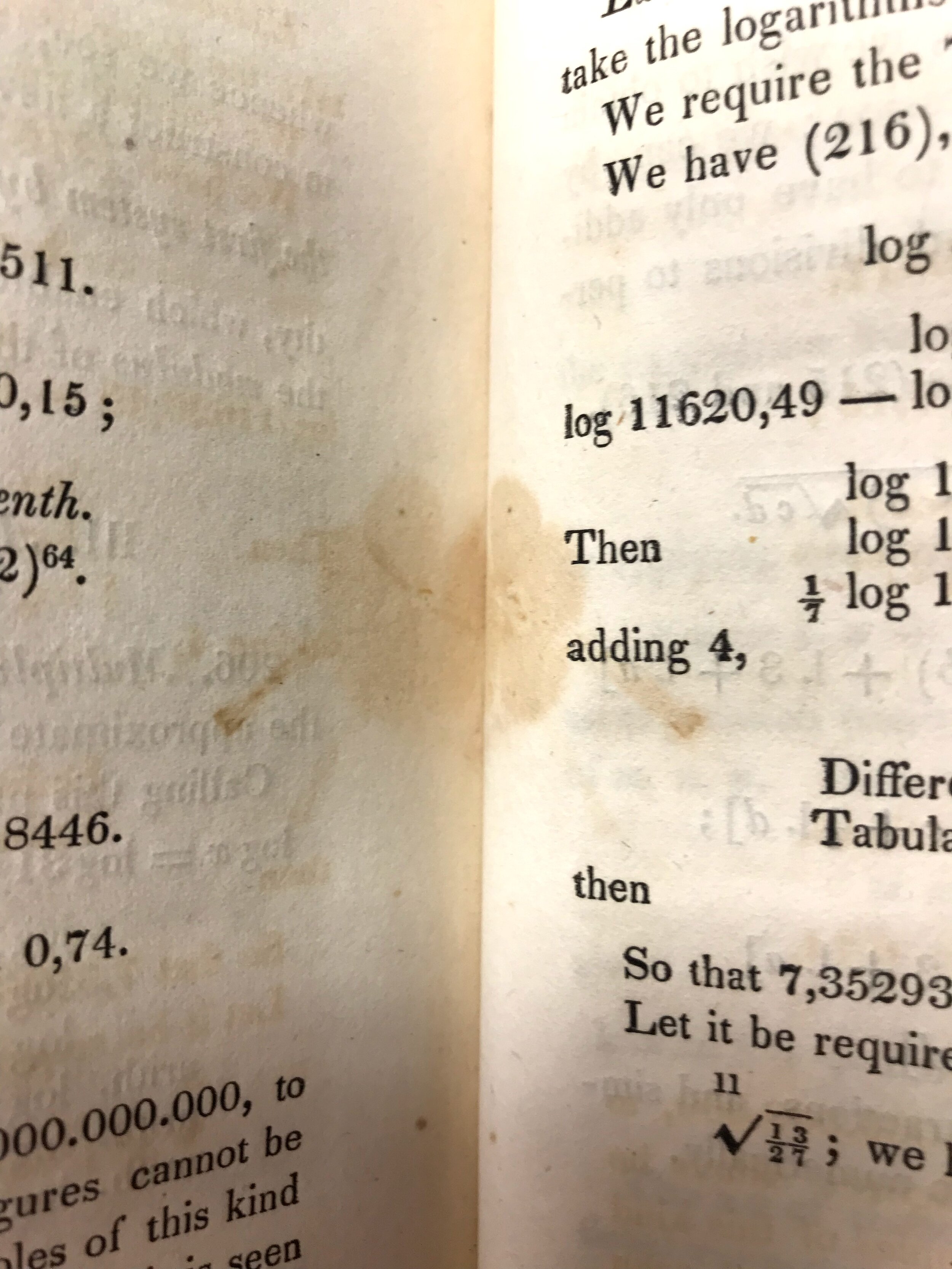

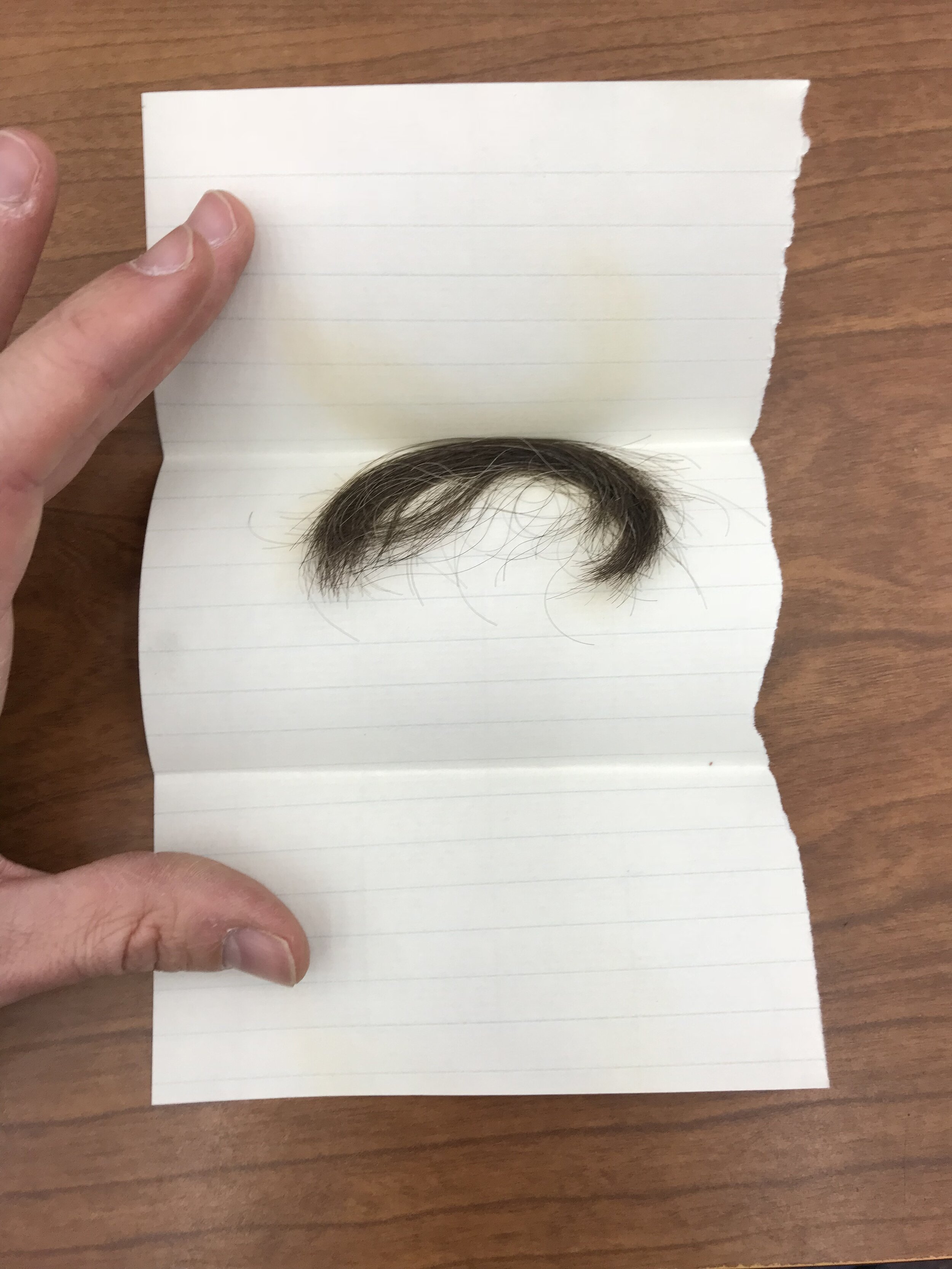

In addition to personally digging for the material, I also thought it wise to interview and get advice on my search from colleagues who deal with books as a profession. At the UW department of Special Collections and Rare Books, the staff was only too happy to reflect on and share some of their favorite finds. The incredible Cairns Collection of American Women Writers was full of volumes that had pressed plants and flowers, locks of hair, and notes. Additionally, the curator and departmental head pointed me to a leaf, inscribed by Robert LaFollette (the image can be found below in the Living Things section); little cutout dolls inside a children’s book; and a 19th century algebra course book with pressed flowers that had left significant stains on the paper. I was assured that there was much, much more but they were difficult to find, the largest challenge being that you could not filter a search for ephemera. While these insertions did not receive its own searchable filter, I was pleasantly surprised to find that the department viewed insertions as important enough to the history of the book that they have a protocol: it states that, when discovered, ephemera should be removed, placed in acid-free sleeves (that sit on the shelf next to its host), and its location and details should be recorded with details on where it was found. This, I discovered, is far from the norm; traditional library protocol relegates the insertions to the dustbins of history.

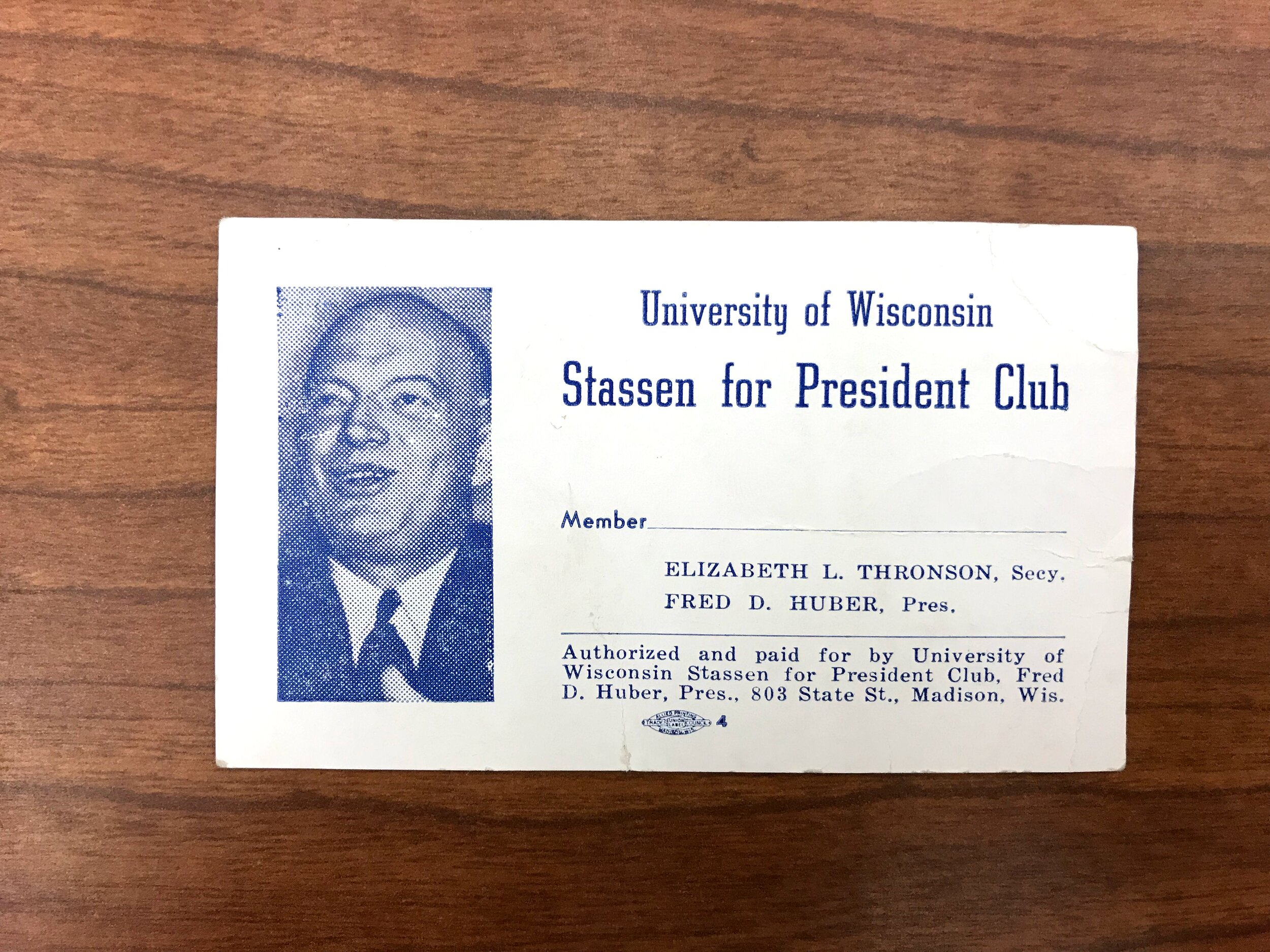

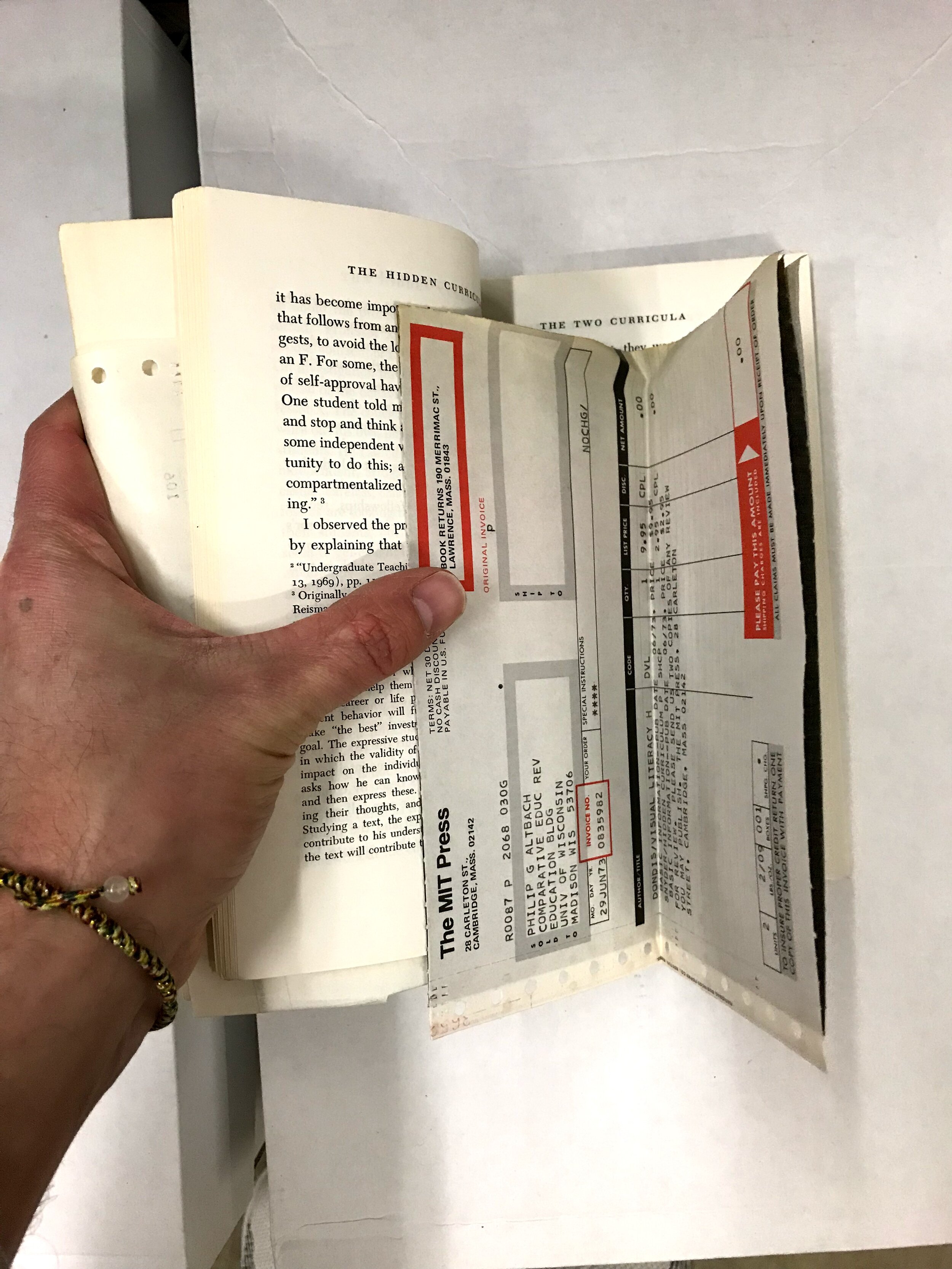

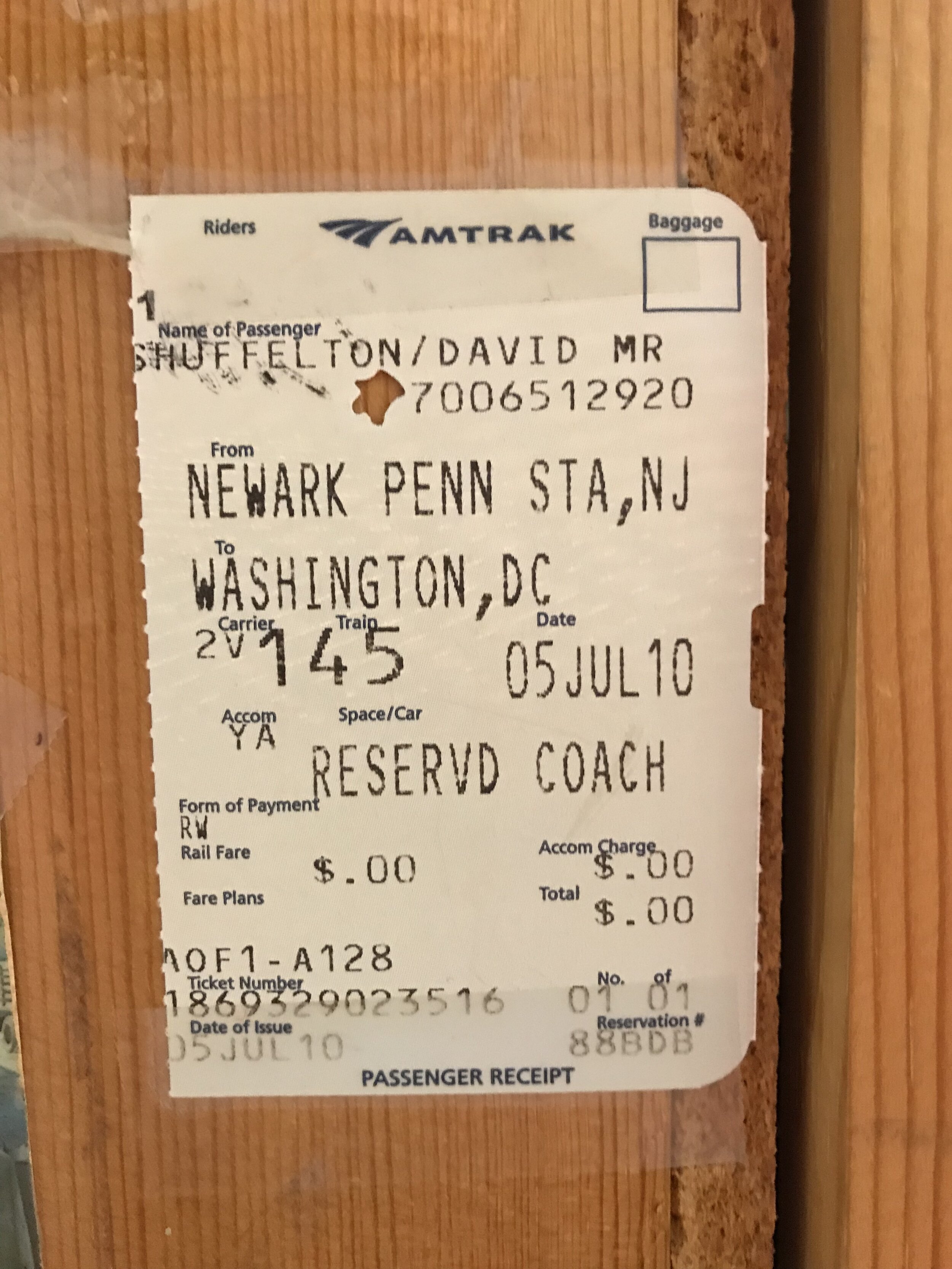

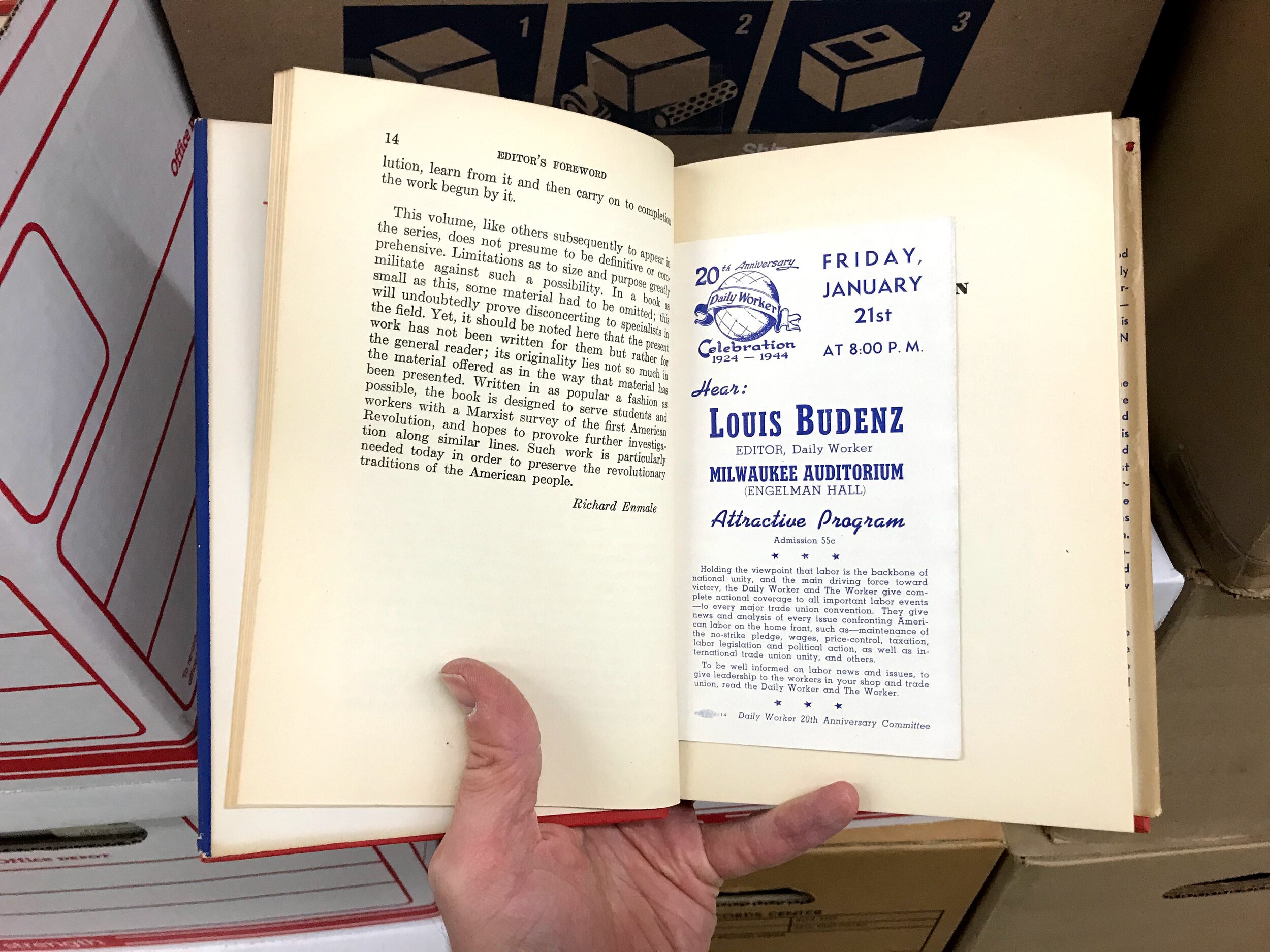

This traditional protocol is largely observed by the Friends of the UW Library. Here, when they circulate through thousands of donated books to be sold biannually, the insertions are removed or thrown out (The reason? So the ephemera won’t damage the books.). The director of the sale generously brought me a collection box of insertions he had saved. I was also able to search a number of donations, which yielded some very interesting connections to the past. These, too, are included in the galleries below.

While I had good fortune at the UW libraries, the greatest evidence I found outside of my own collection were in the archives of the Wisconsin Historical Society and Paul’s Books in Madison, Wisconsin.

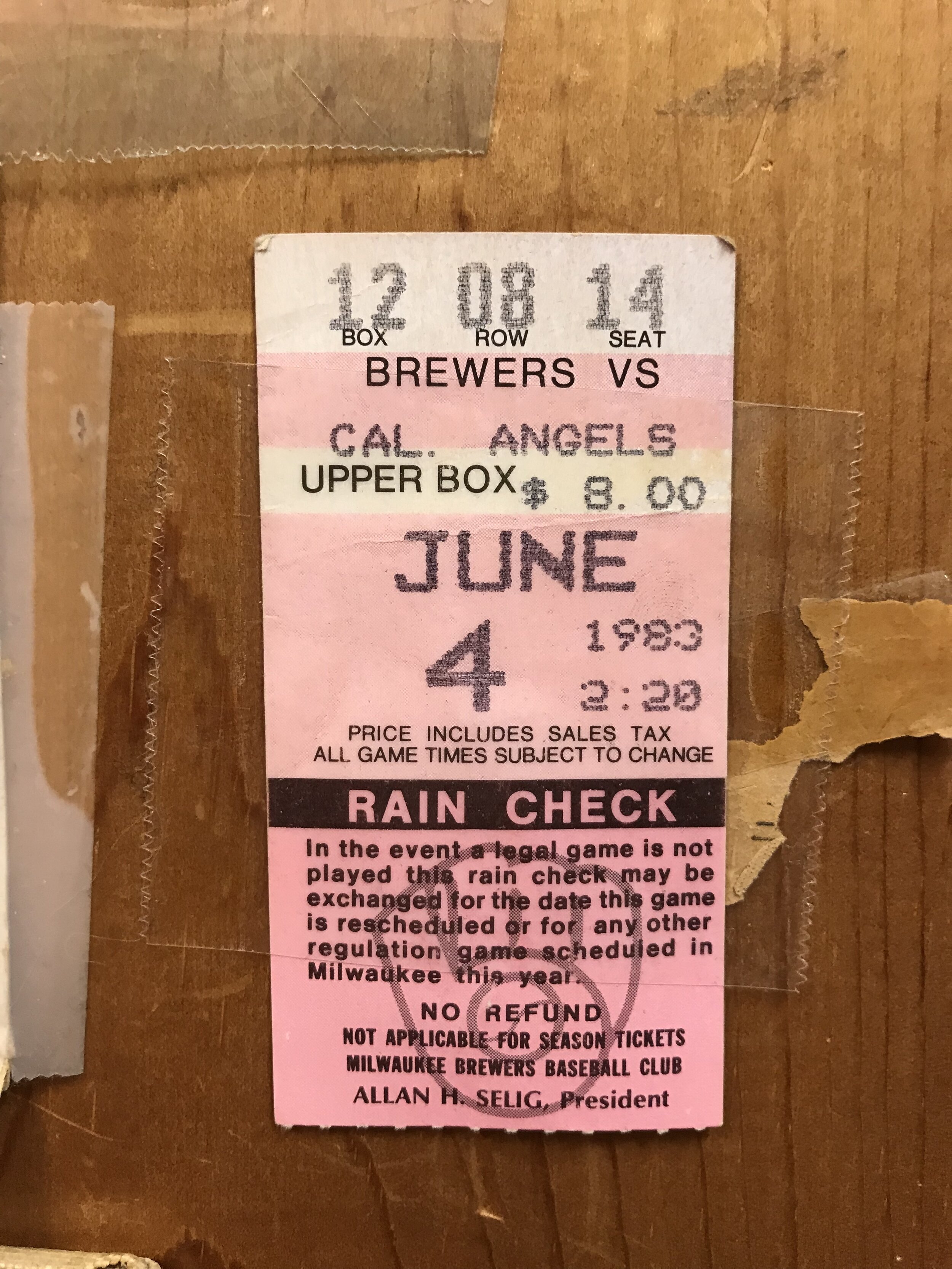

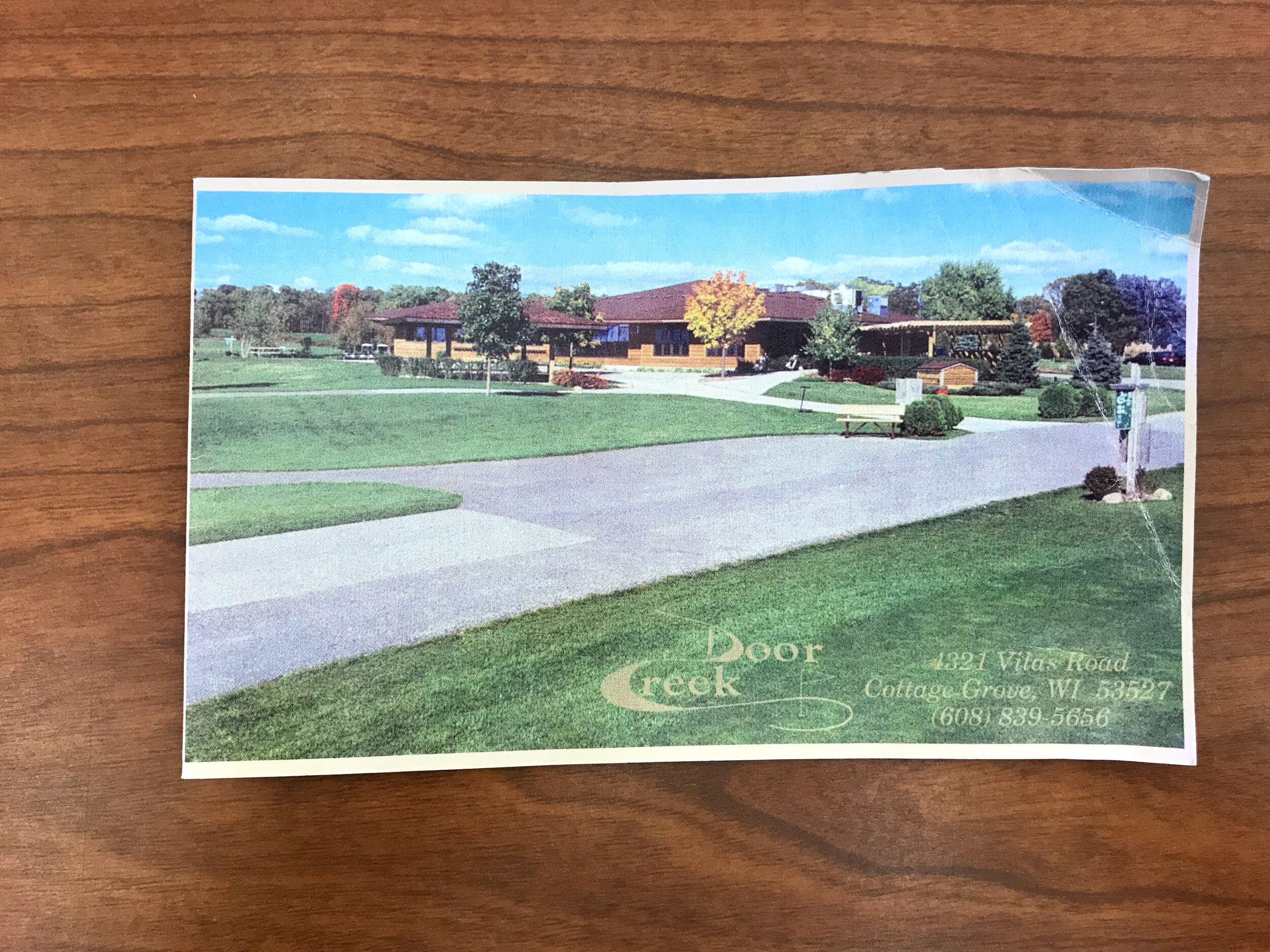

The Wisconsin Historical Society building in Madison, Wisconsin

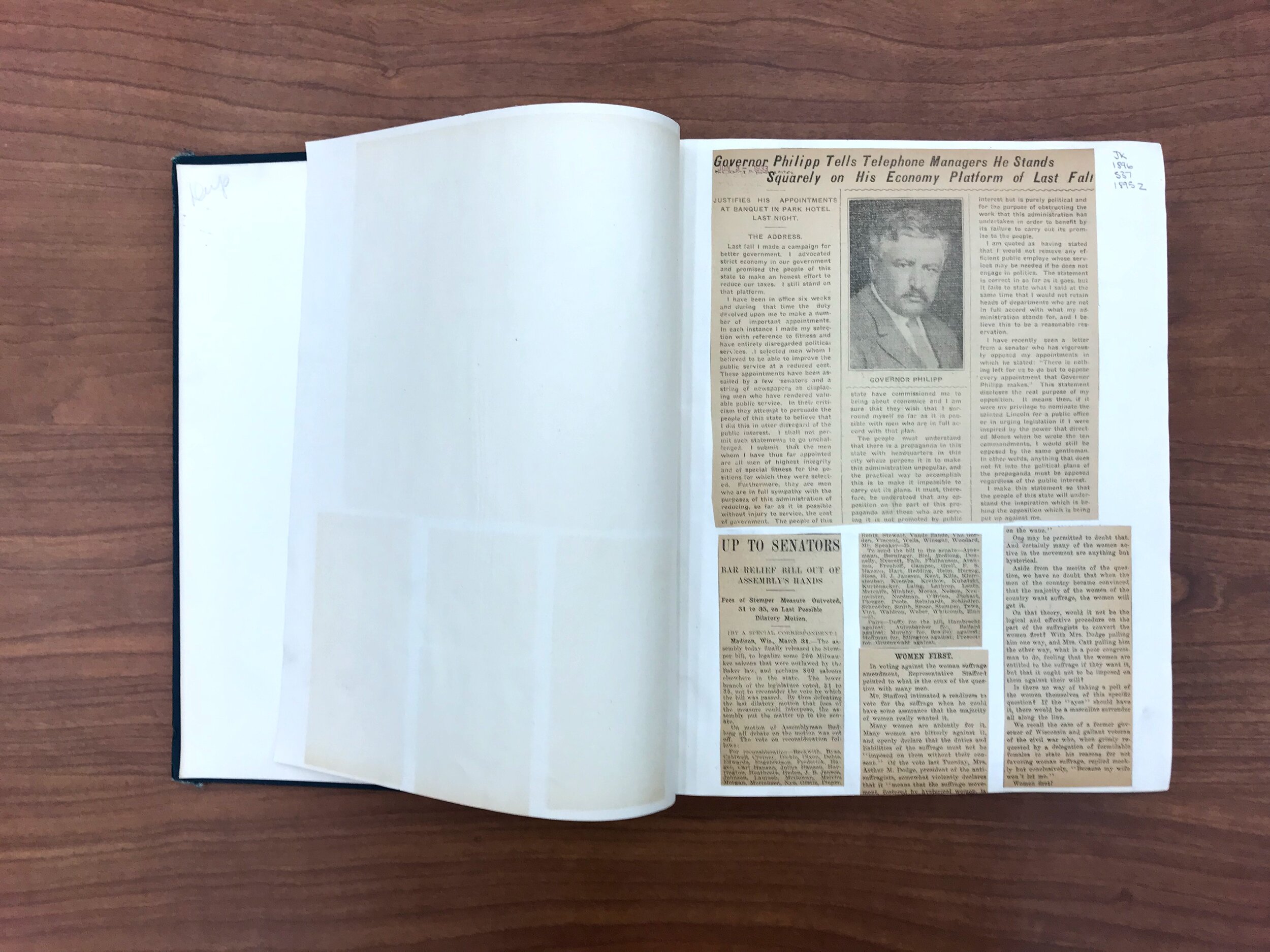

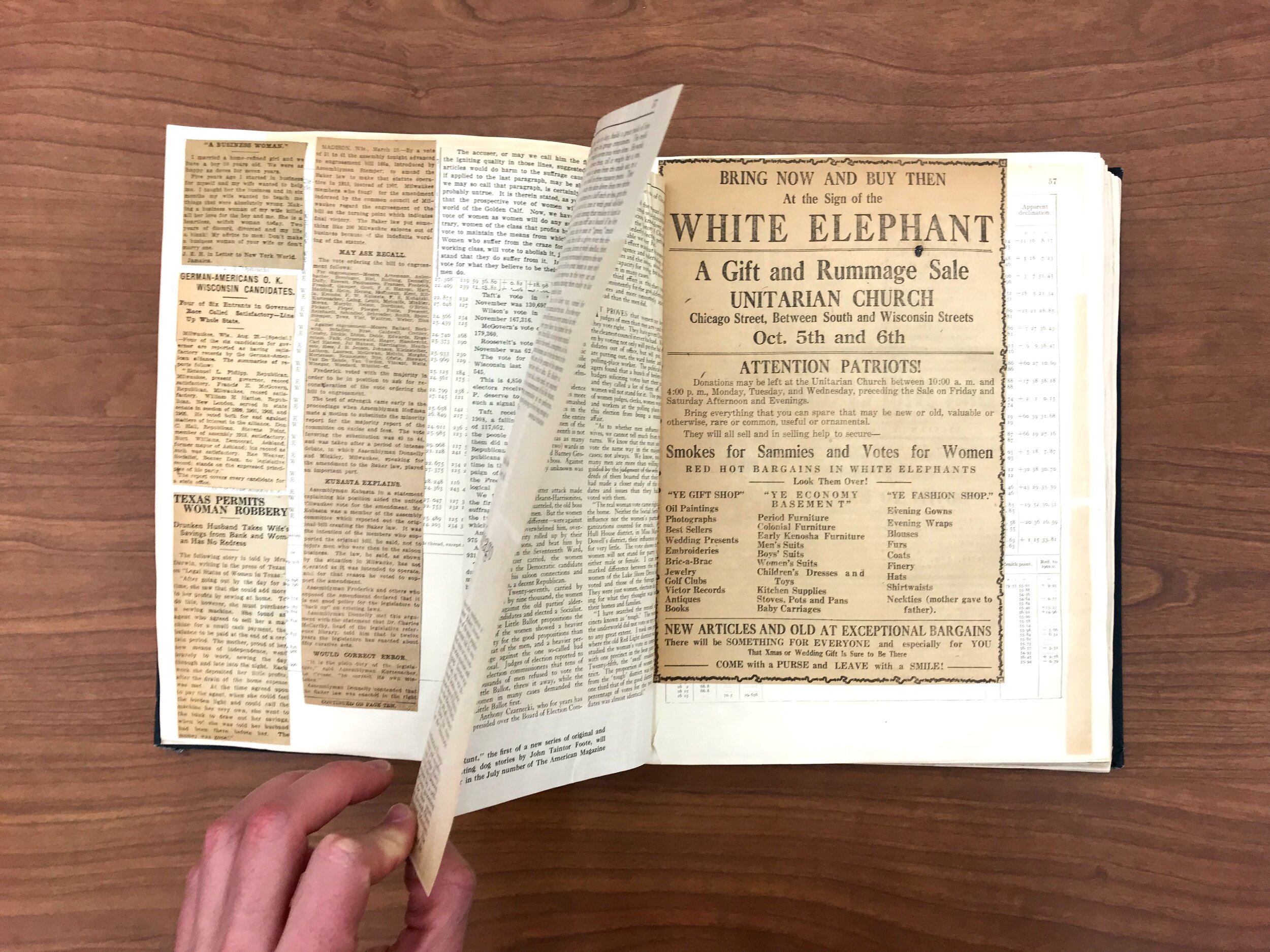

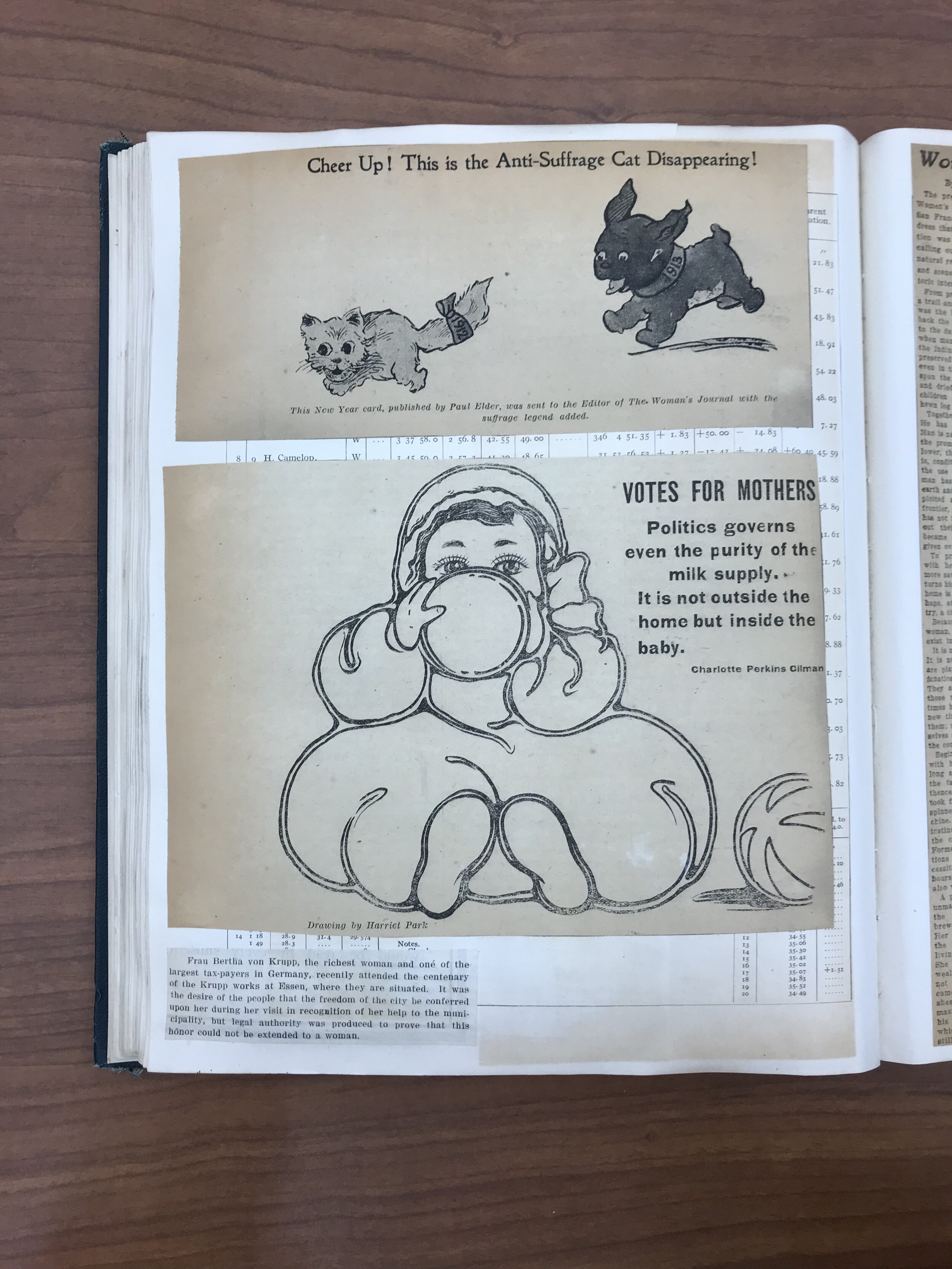

The archives of the Wisconsin Historical Society are located on the library mall in the center of the University of Wisconsin. Its simply appointed archives reading room, located on the fourth floor of a neoclassical building, betrays the immensity of their collection. As I would soon discover, the staff had an incredible knowledge and connection to their collection. After asking their Senior Reference Archivist about “things stored in books,” his recollections and resources grew by the minute. Even though insertions are not systematically categorized in their system, he instantly recalled a number of items which got to the heart of what I was looking for: an envelope with a lock of hair pressed inside of a book; a naval data guide repurposed as storage for items related to the women’s suffrage movement; a pharmacist’s ledger used as storage for notes. “I used to put bills in books,” he later confided to me, which caused him to miss a payment. I assured him I had done the same thing; like many others, I too, stored bills, money, ticket stubs, and receipts in books.

The archivist then directed me to his colleagues, who all had stories. He first called the Collections Development Coordinator on the phone. “I have a patron here who is interested in things found in books,” he started. After a brief few moments of listening to the other end, I heard him respond, “So, you’ve been collecting these?...do you have them?...would you be willing to show them to a patron?...when?...great, I’ll see you soon.” Within five minutes, his colleague showed up with a collection of insertions. She was as happy to share them with me as I was to browse them. “You know, I see everything that comes in to our collections, so I just figured it was a good idea to collect these. You never know, maybe it would be good for an exhibition in the future,” she volunteered. Huddled around the items, we were joined by a number of other employees, who all had their own stories as well as stories from employees of the past. “Cosmic archive experiences,” was how one employee referred to these historical encounters. While most of the memories referred to items that lay in the periphery of their minds as well as the catalog, it was clear we shared an interest in the ability of these ephemera to connect us with the past. This interest, I was coming to discover, was even more common than I had thought; maybe I didn’t realize this because like many peripheral memories, they are rarely recorded and thus lost to history.

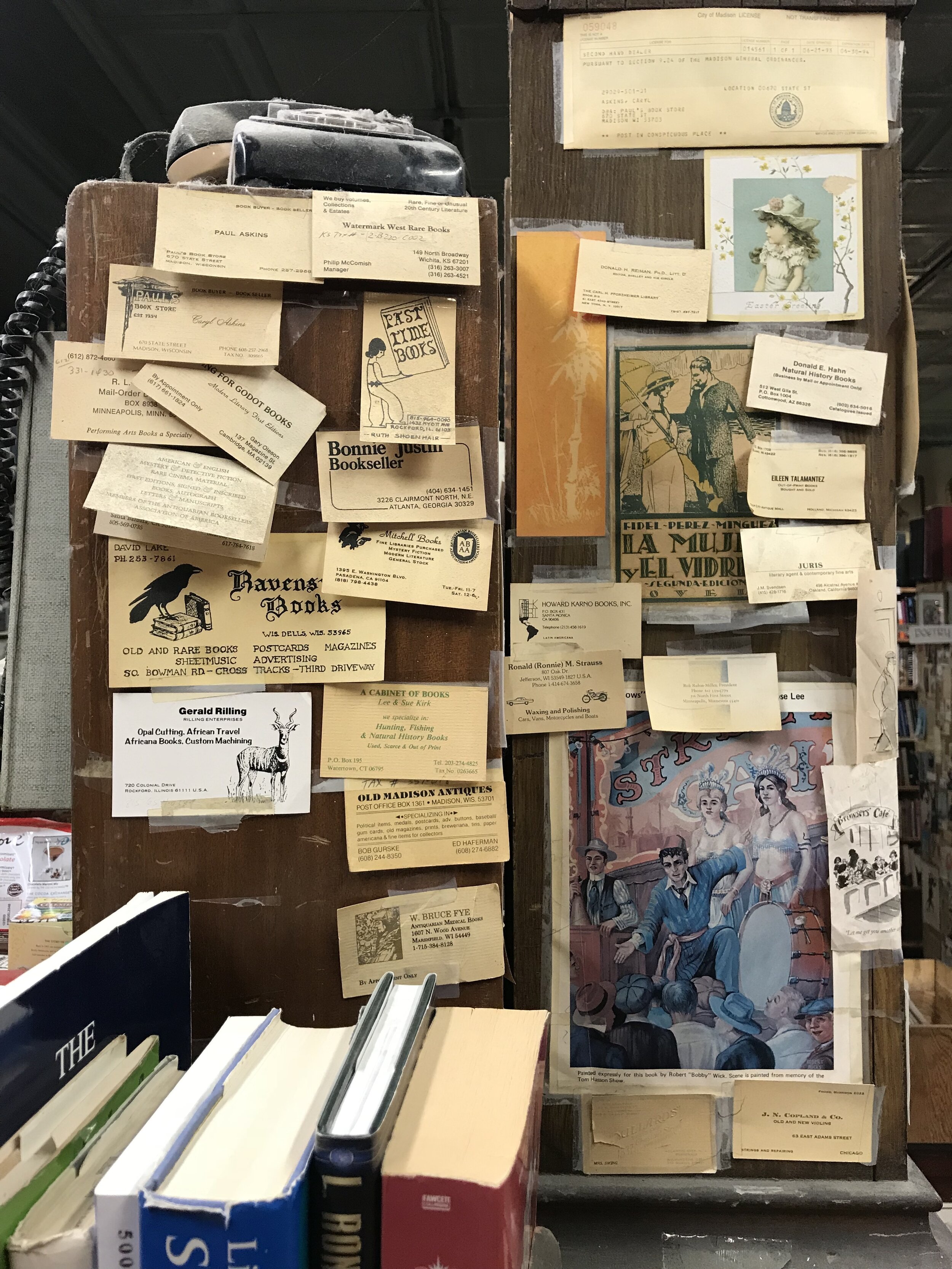

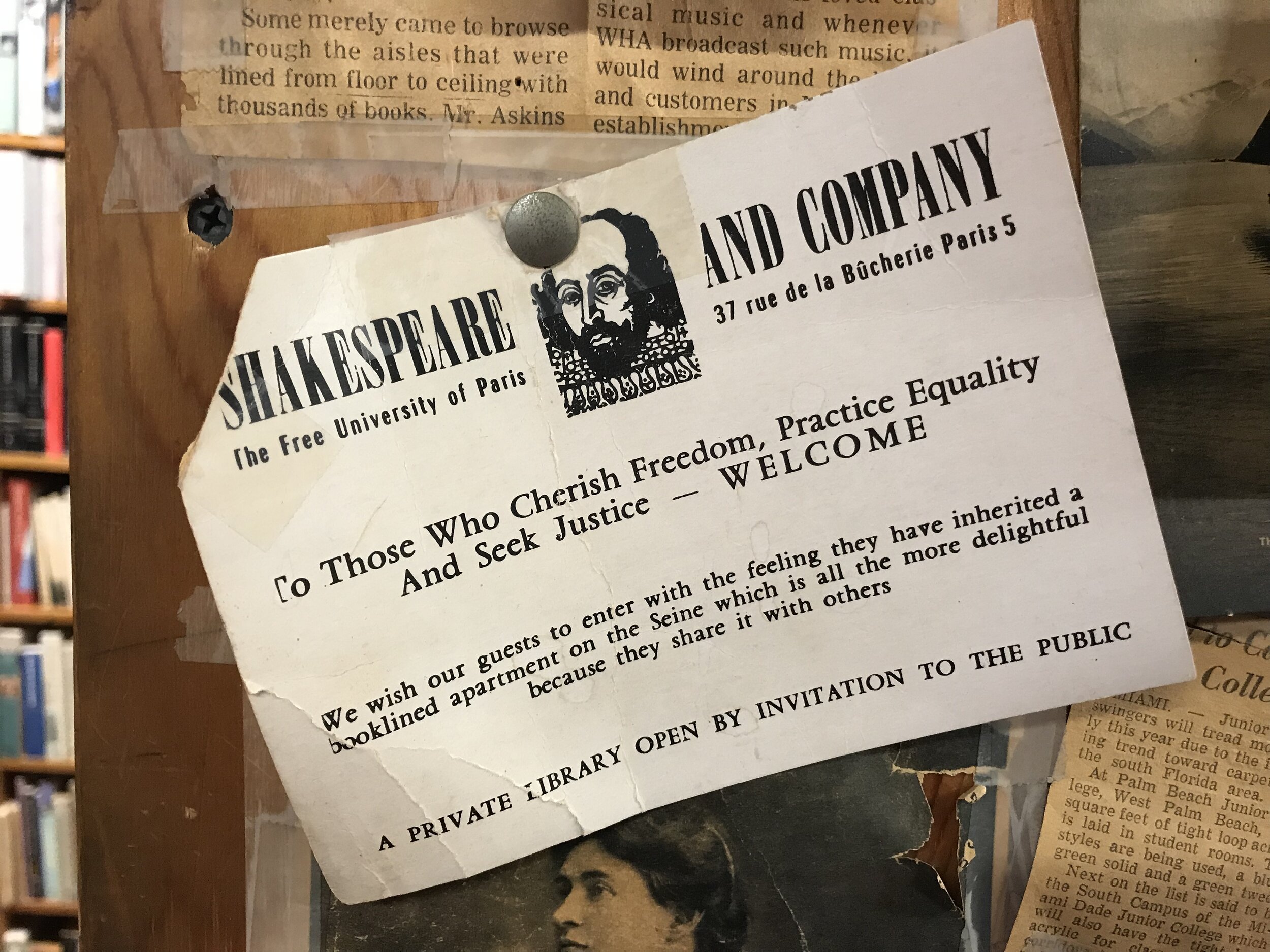

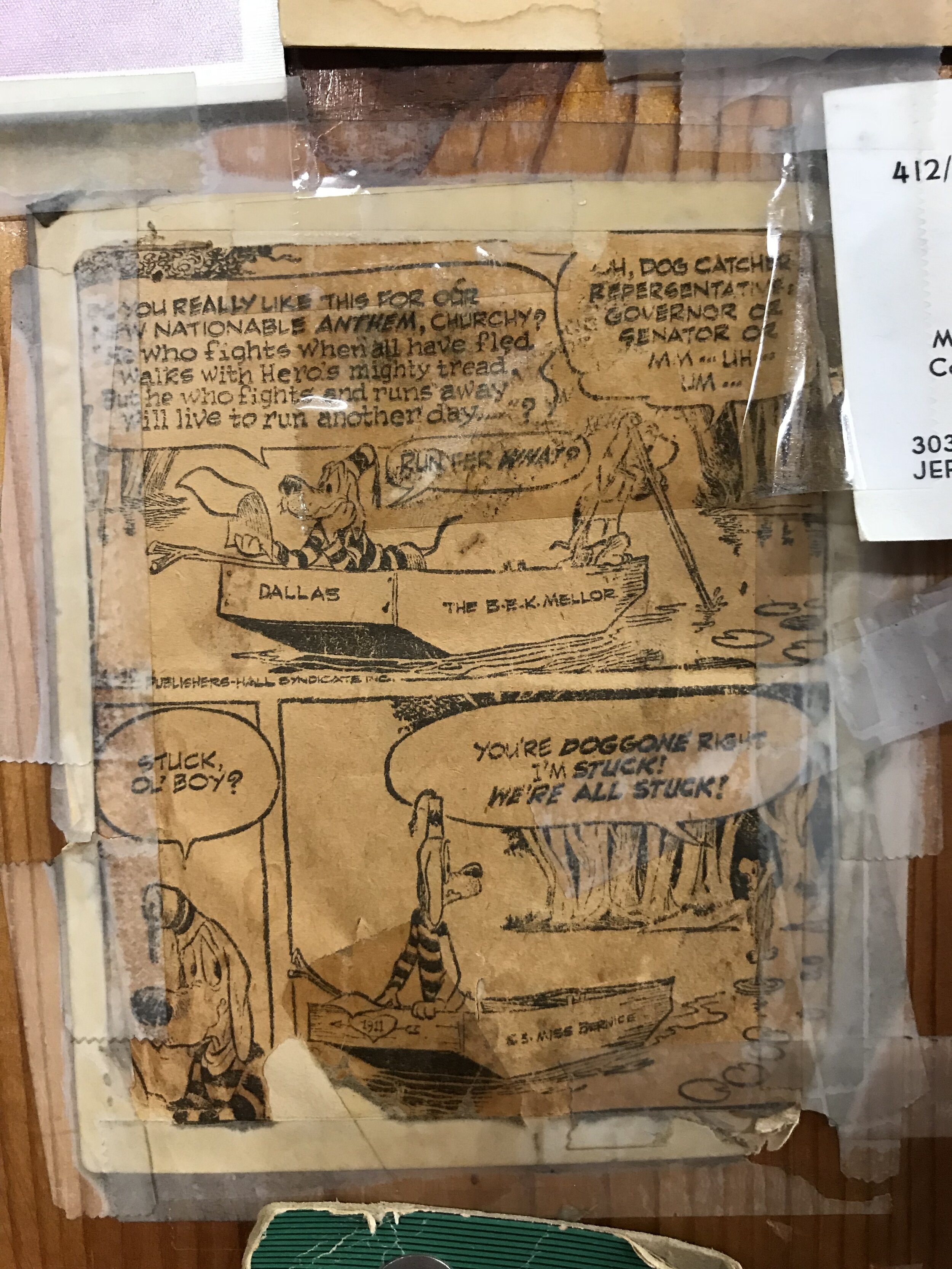

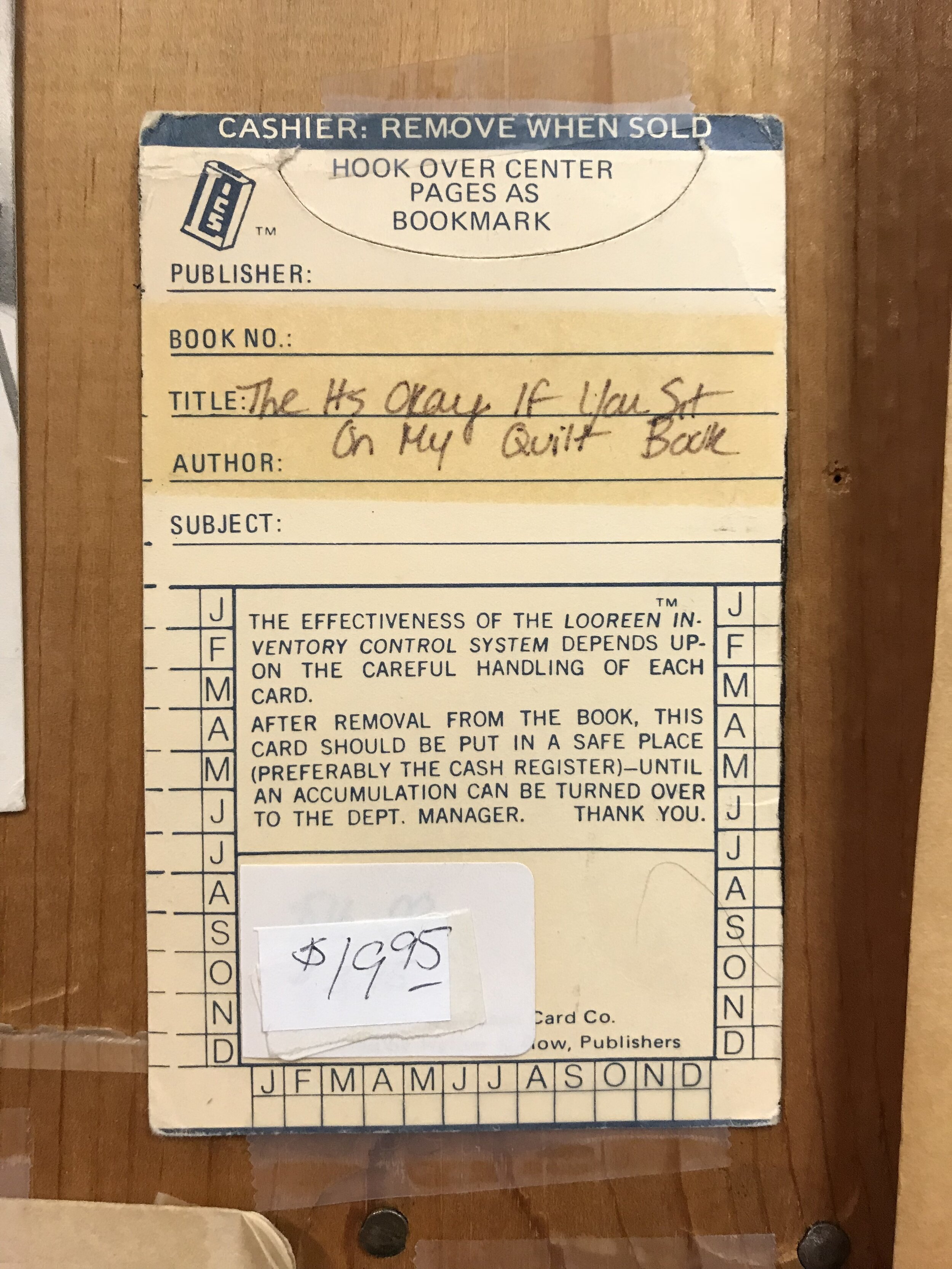

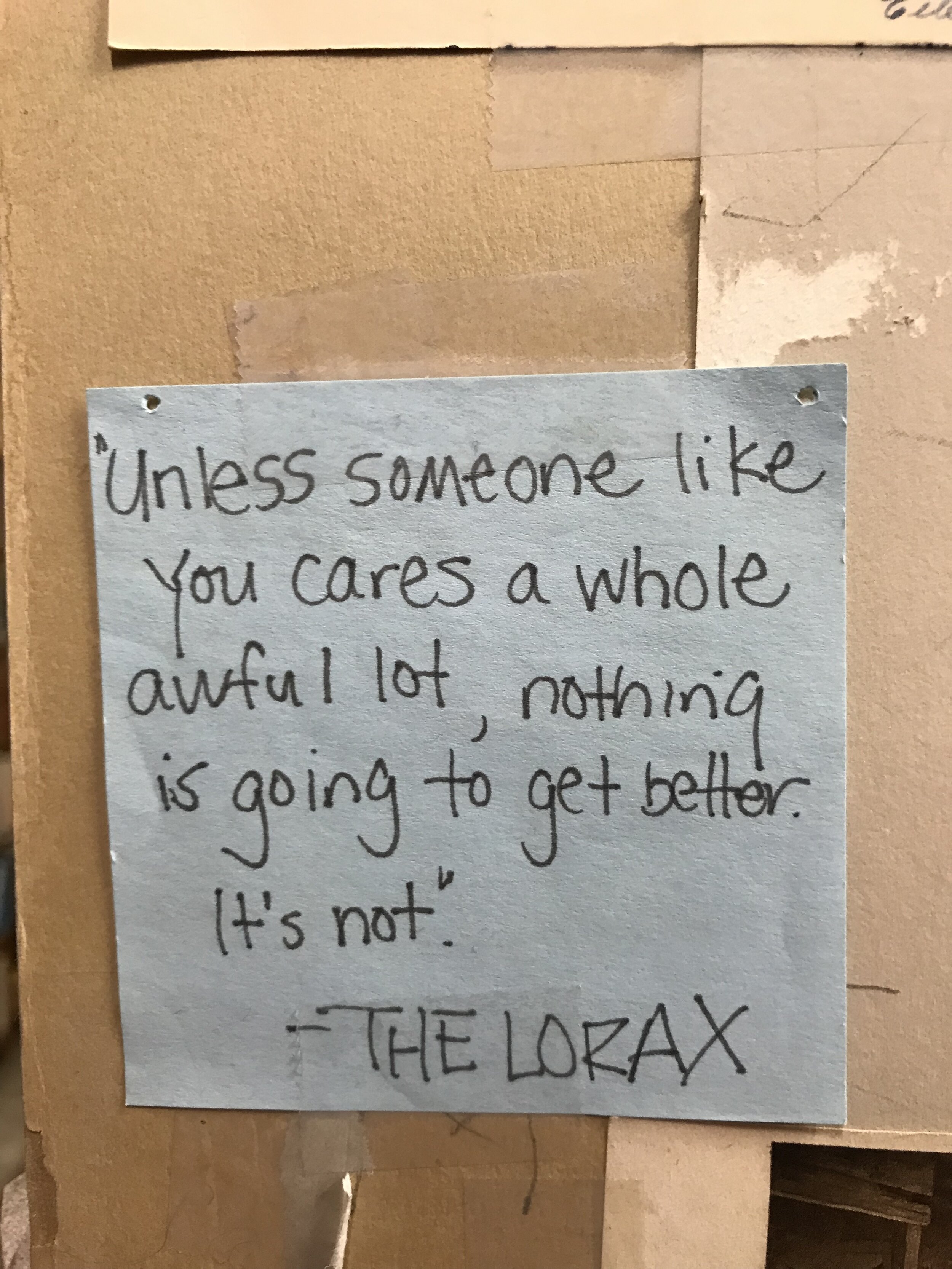

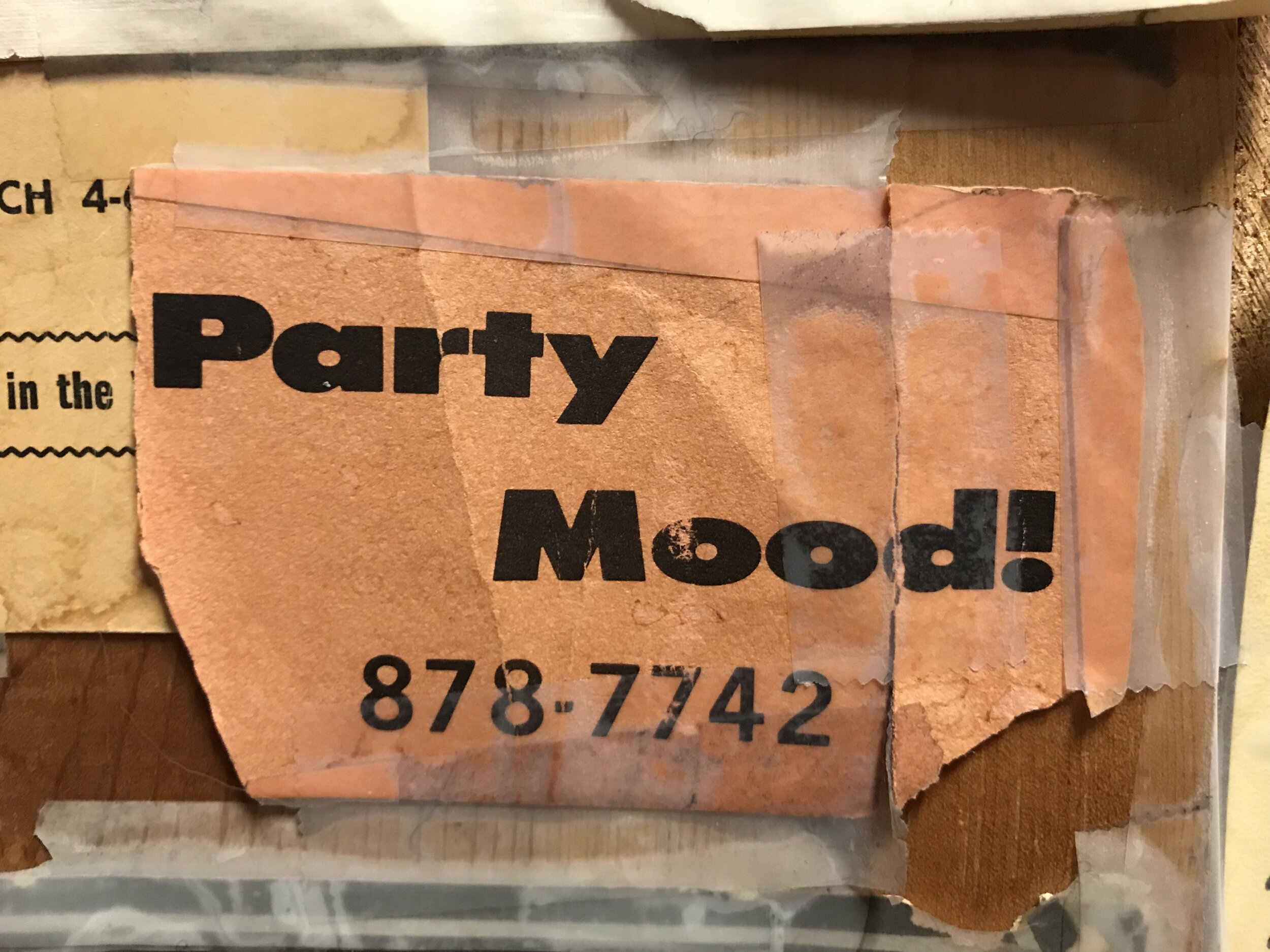

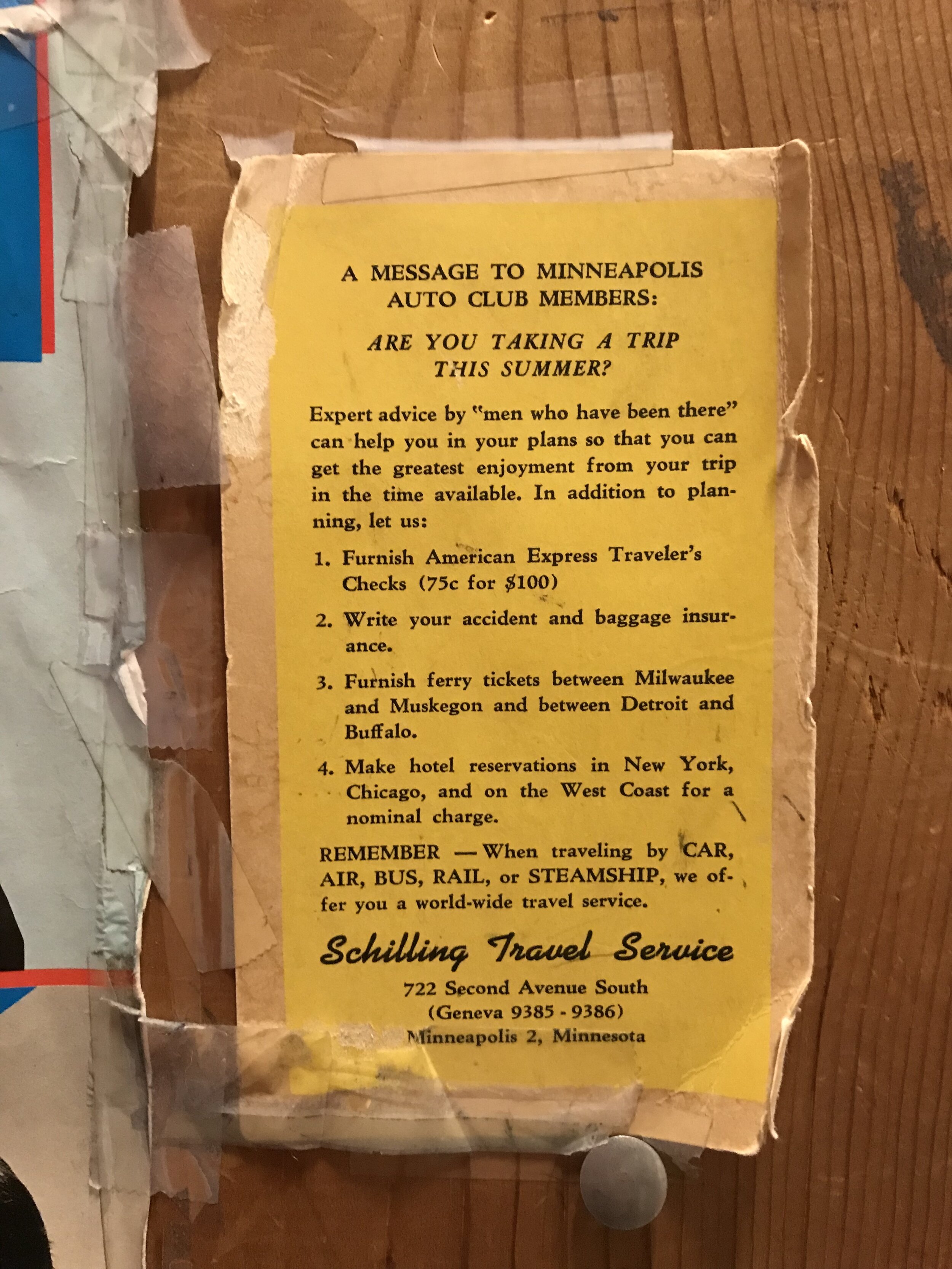

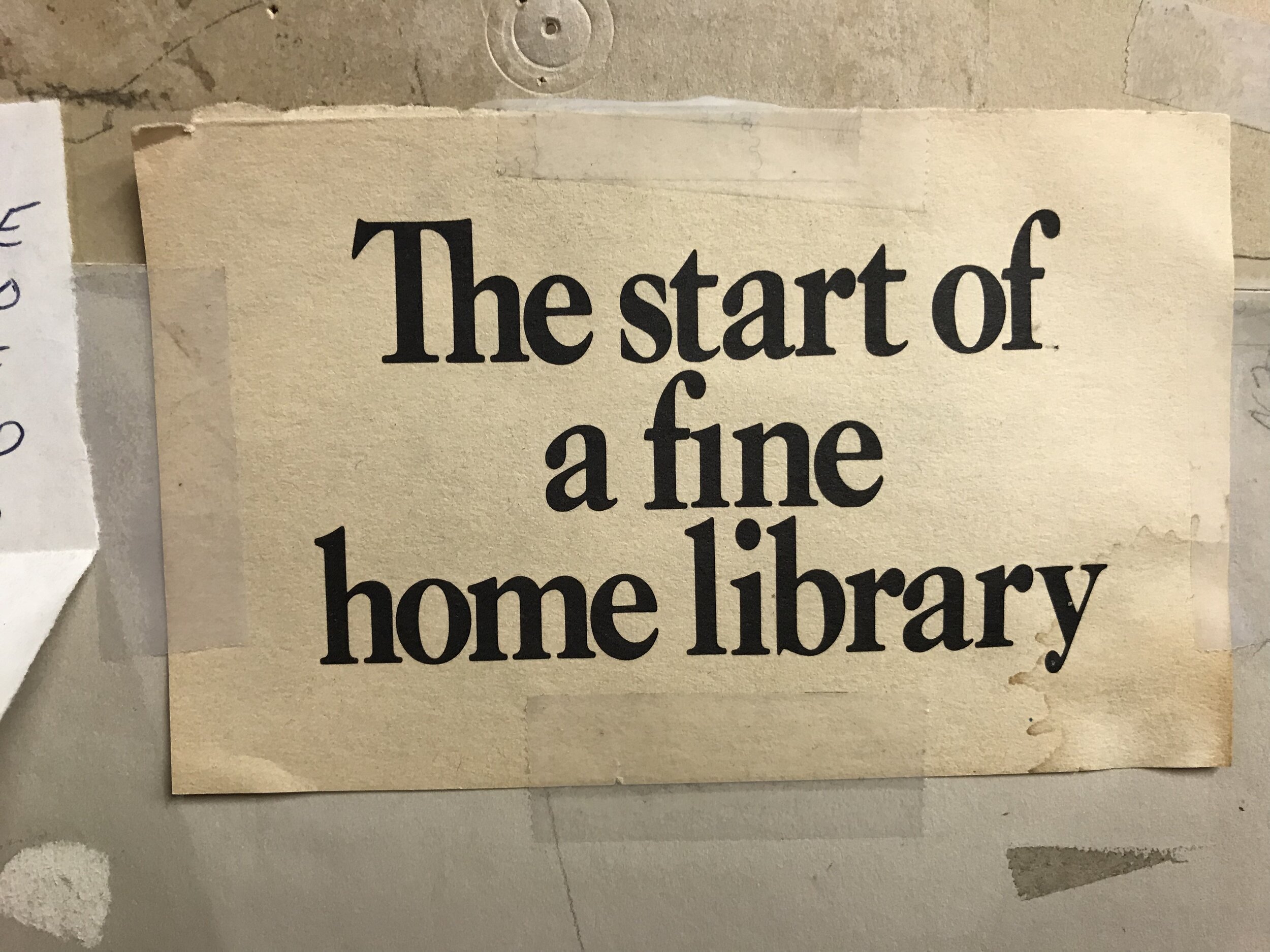

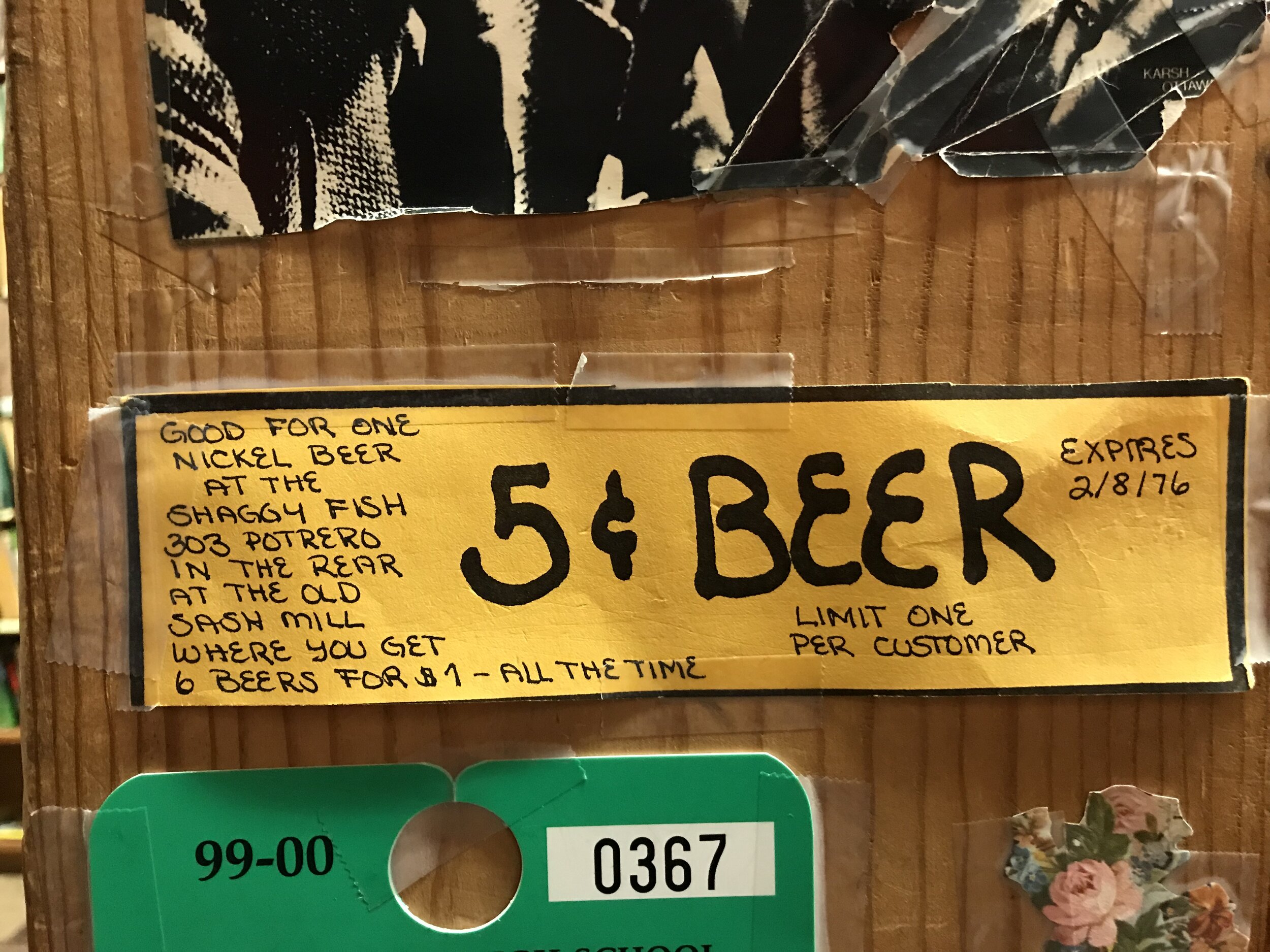

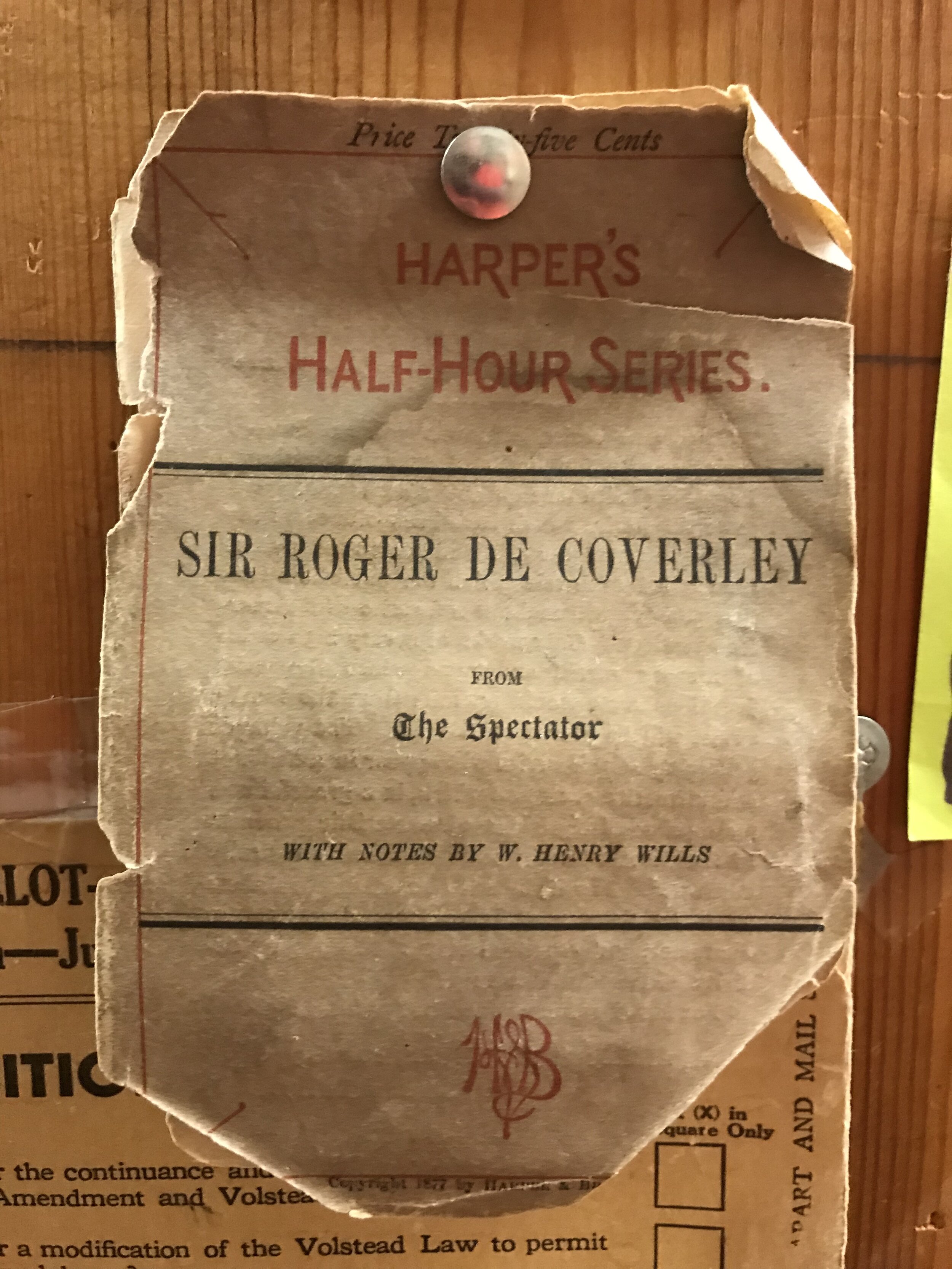

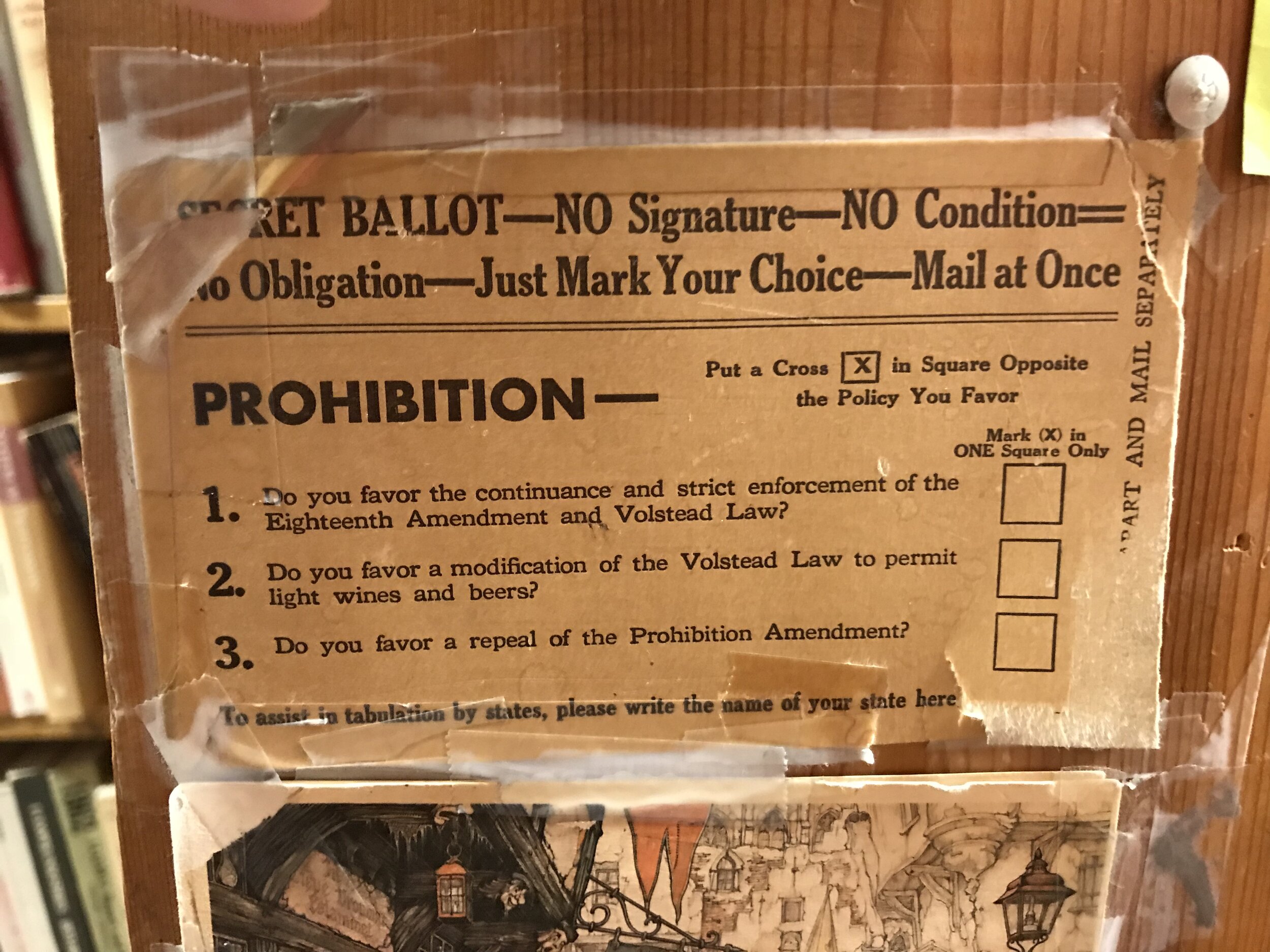

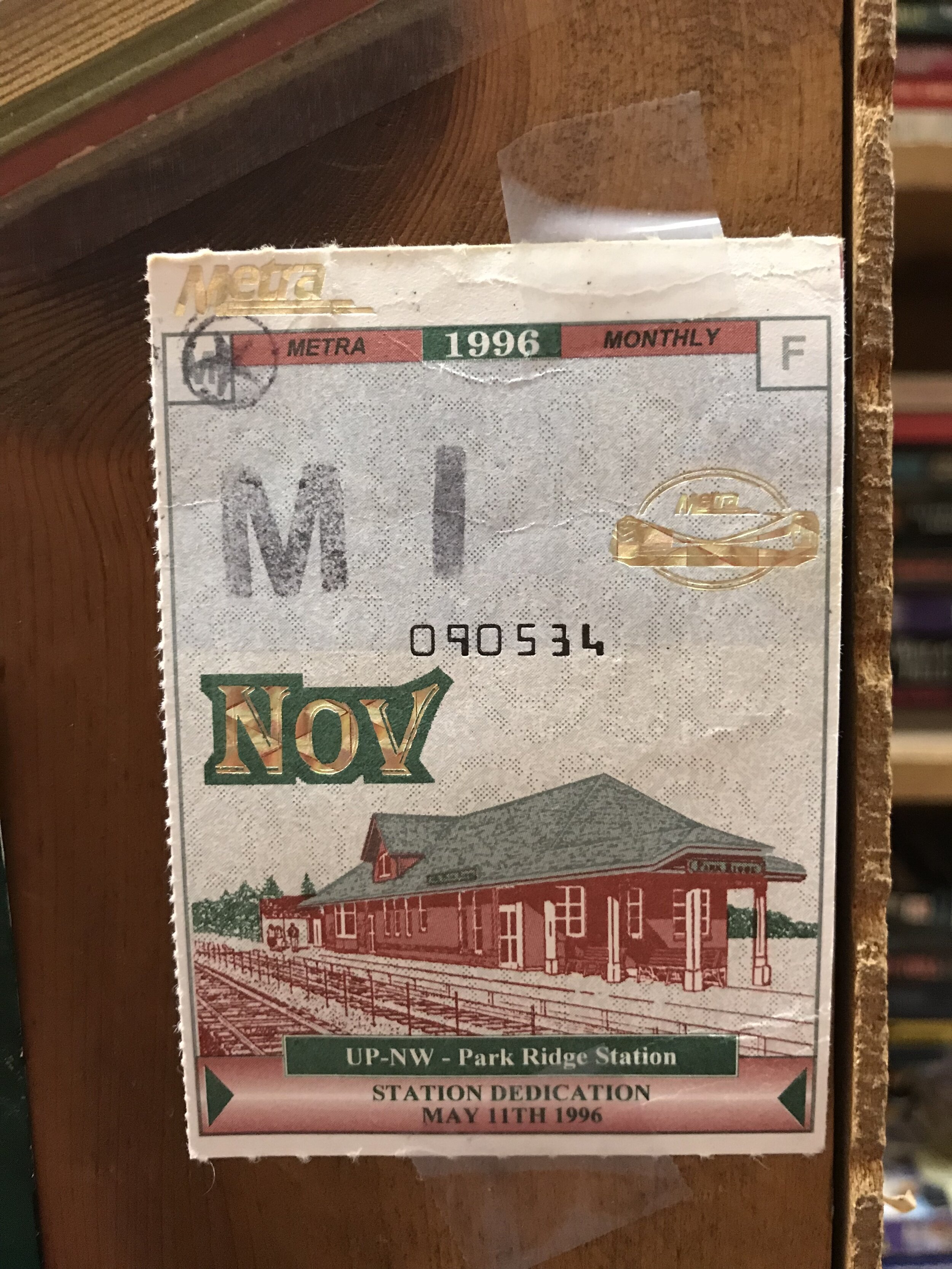

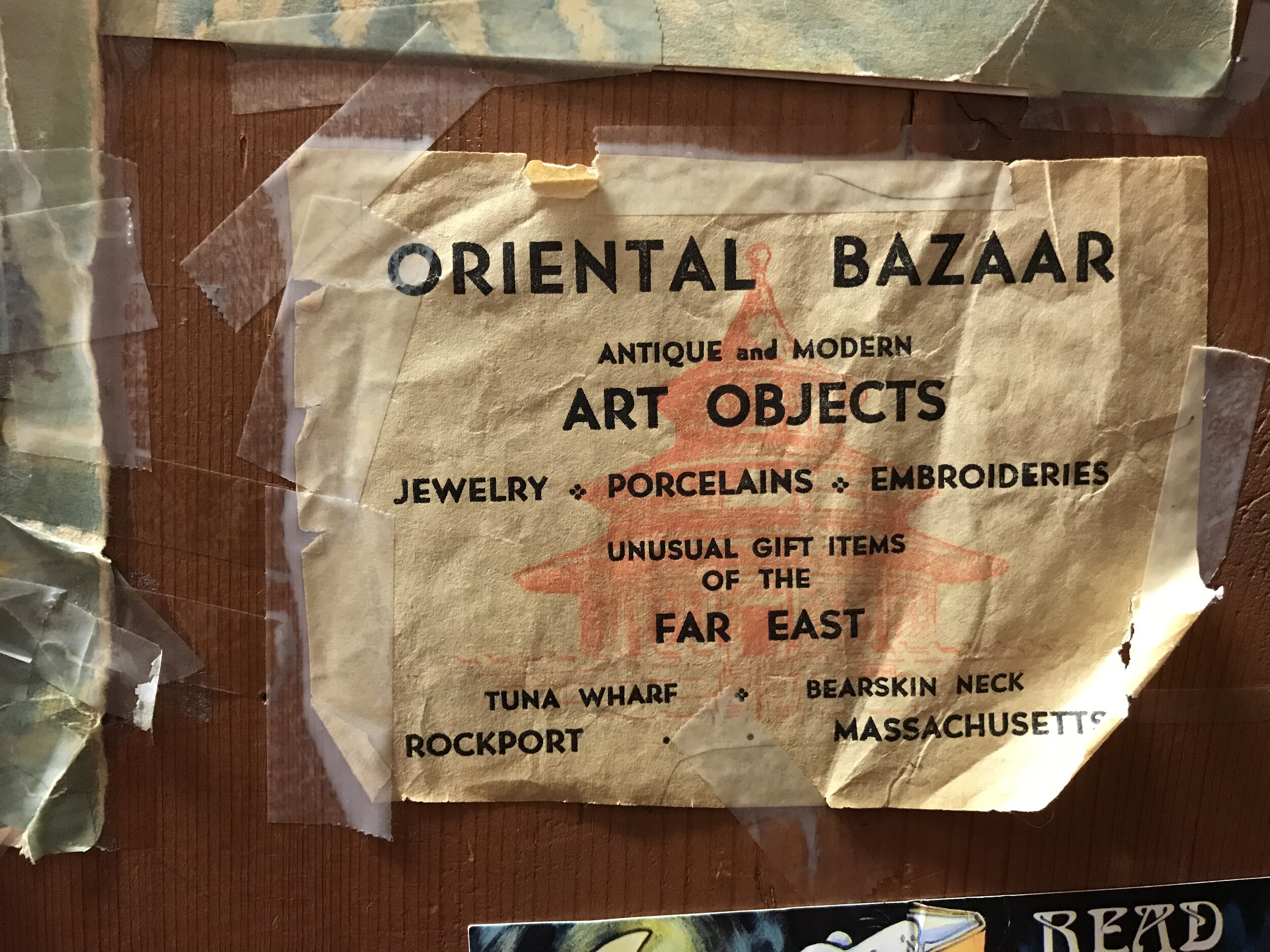

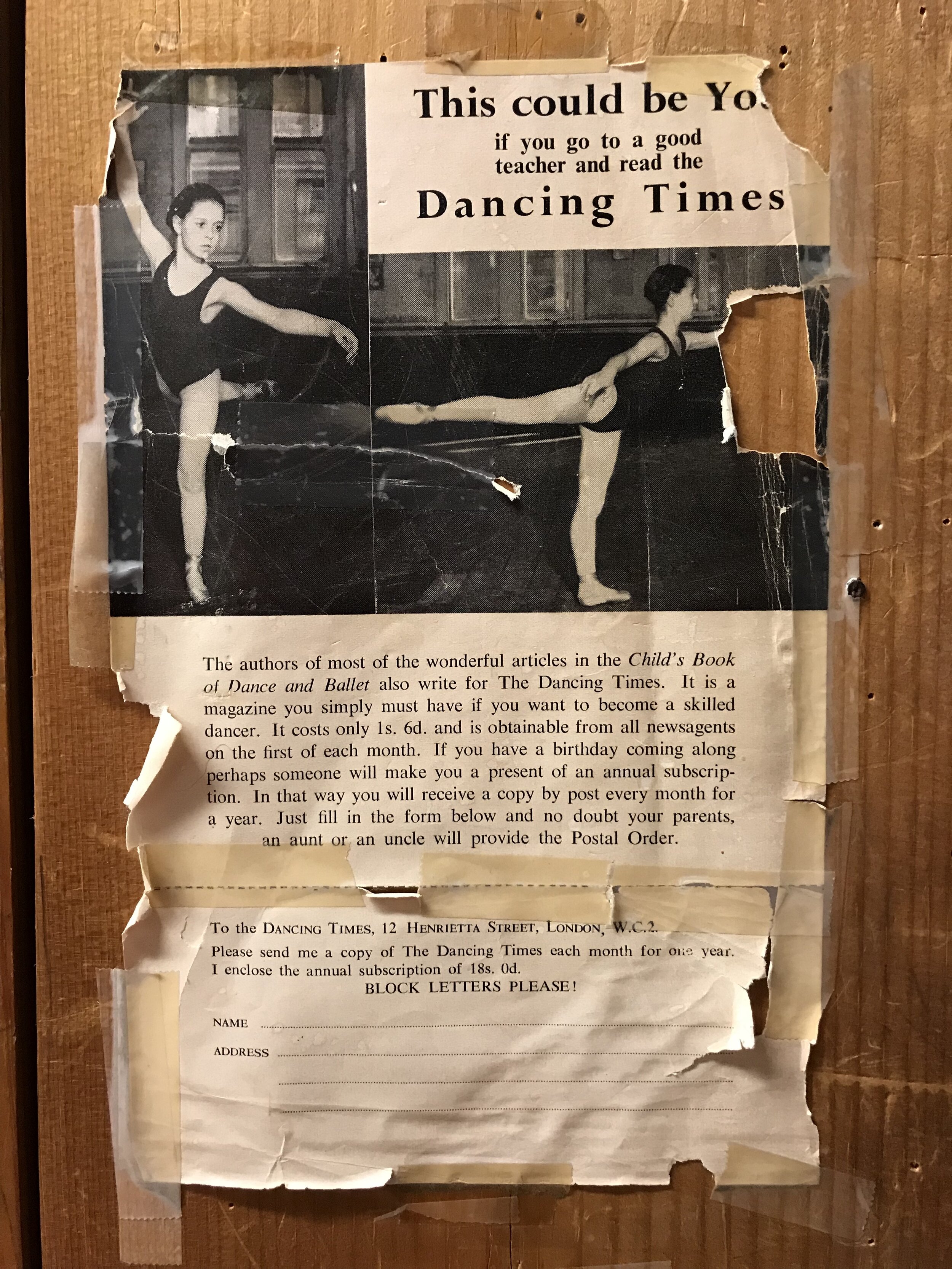

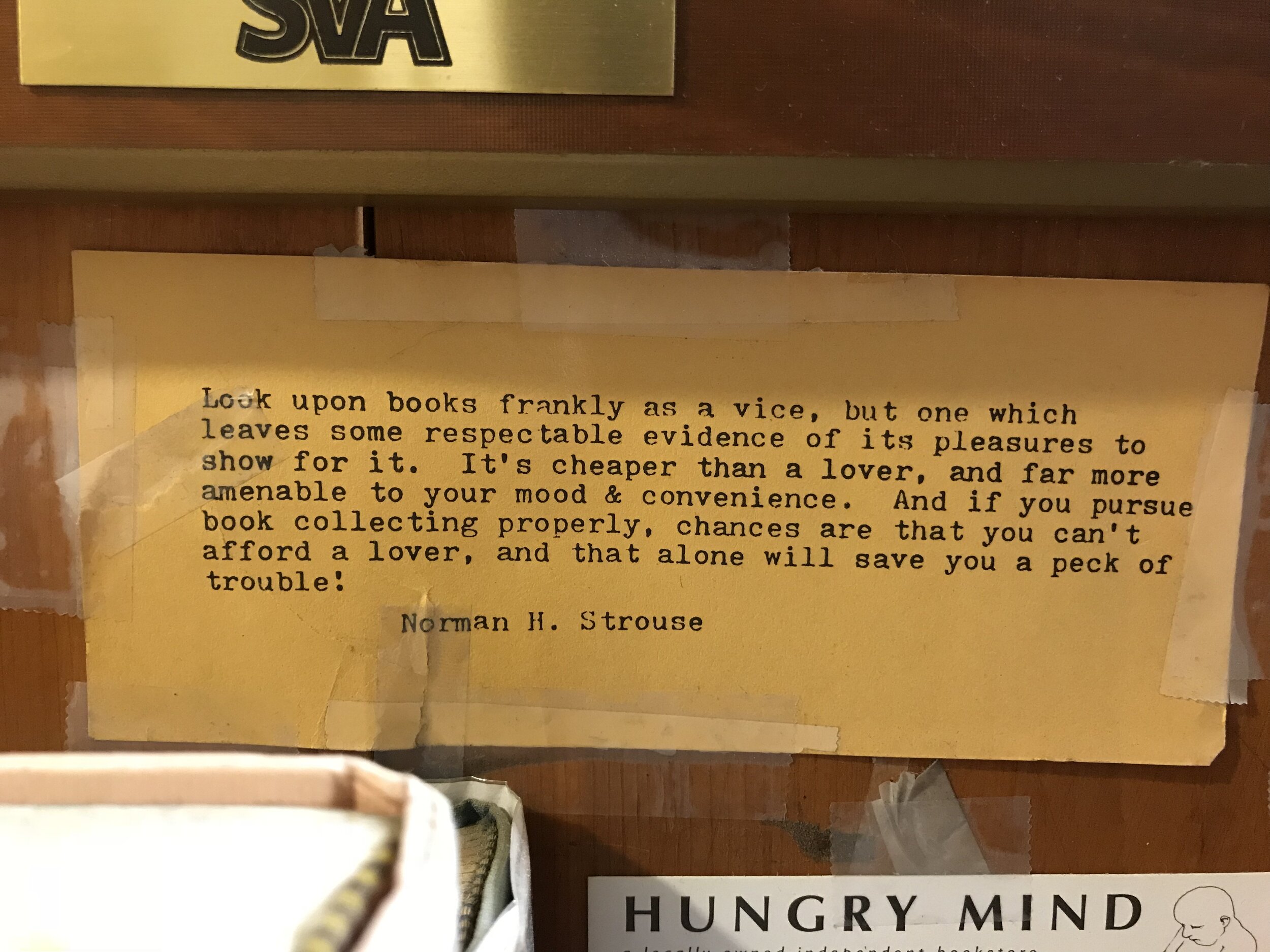

Down the street from the Wisconsin Historical Society are two bookstores, Browzer’s and Paul’s Books. I dropped into Browzer’s and asked about the things they have found in books; they often would save insertions, the employee said, but their usual stack had just recently been tossed. “Check outside there on the wall, though,” she told me. Framed and hanging right next to the door was a collage. “Those are all things we’ve found in books…and we made that little poster.” Having visited the store many times, I had overlooked this most clear example of ephemeral evidence. Included in the collage were hundreds of individual items including transportation stubs, business cards, and tickets for concerts, galas, raffles, and plays.

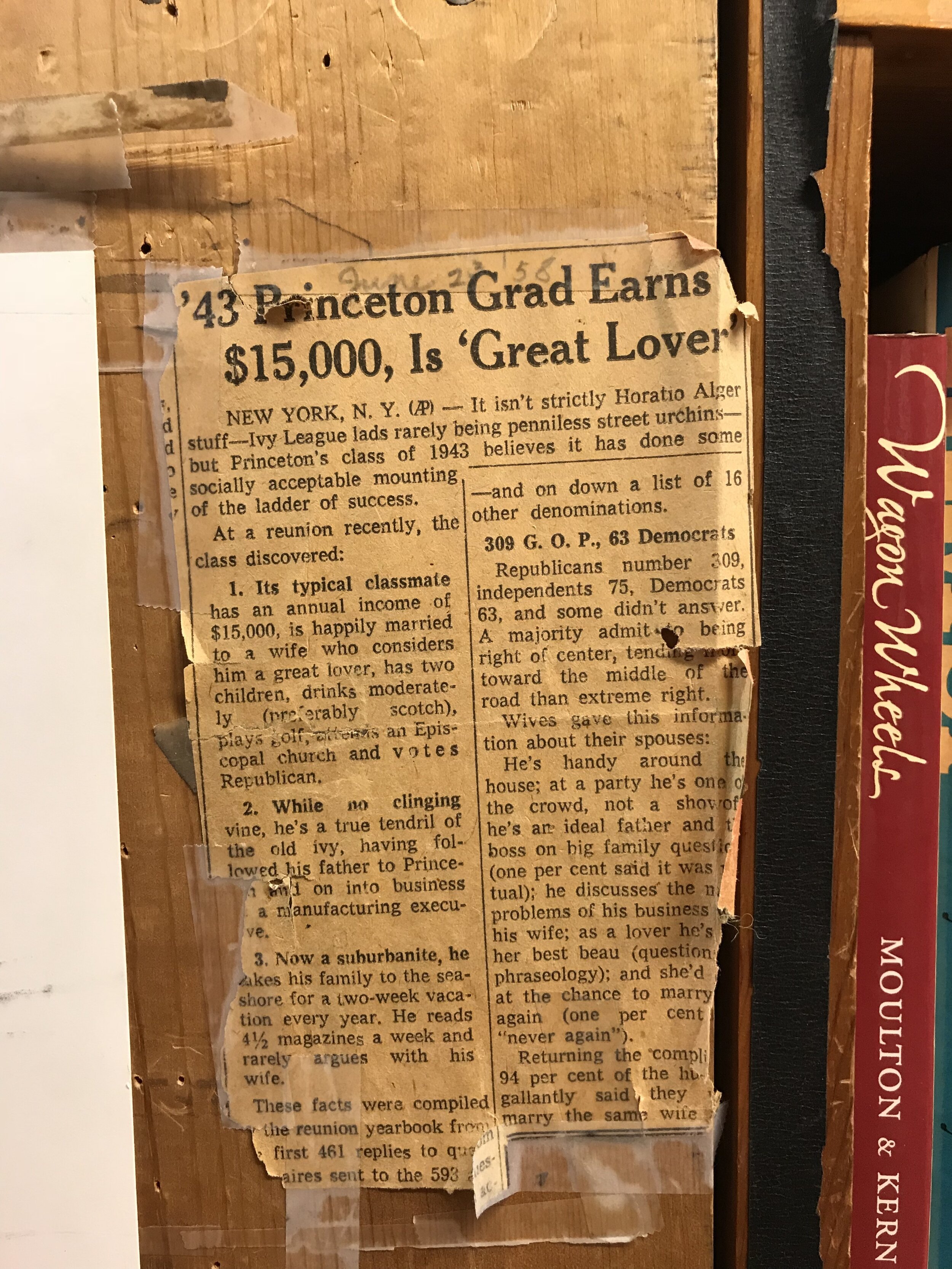

Even more overlooked were the walls and ends of the bookshelves at Paul’s Bookstore, established in 1954 by the current proprietor’s late husband. After asking the owner if she saved the items found pressed in books, she answered, “That’s what you’re looking for,” and pointed at the walls. I’d never realized that a favorite haunt of my undergraduate and graduate years had always had thousands of insertions pasted on the walls. Taking photographic record of just a small portion of her finds, my collection grew exponentially. These, too, are included in the galleries below.

Paul’s Bookstore, circa 2019. Removed insertions can be seen taped to the empty vertical spaces.

VI.

I was thrilled to have a large collection of these insertions but noticed that — except for those found in the stacks or in friends’ collections — a majority of my finds were divorced from their resting place; the insertions had been uninserted. These orphaned ephemera still carried with them connections to the past, but a major cross-referencing connection had been lost, and lost forever. What I was intrigued by most — what I wanted to find more of — were the insertions still in their improvised capsule, the book. For me, I cared most about the potential to connect with the past. As I looked through my own collection, I found what I was looking for.

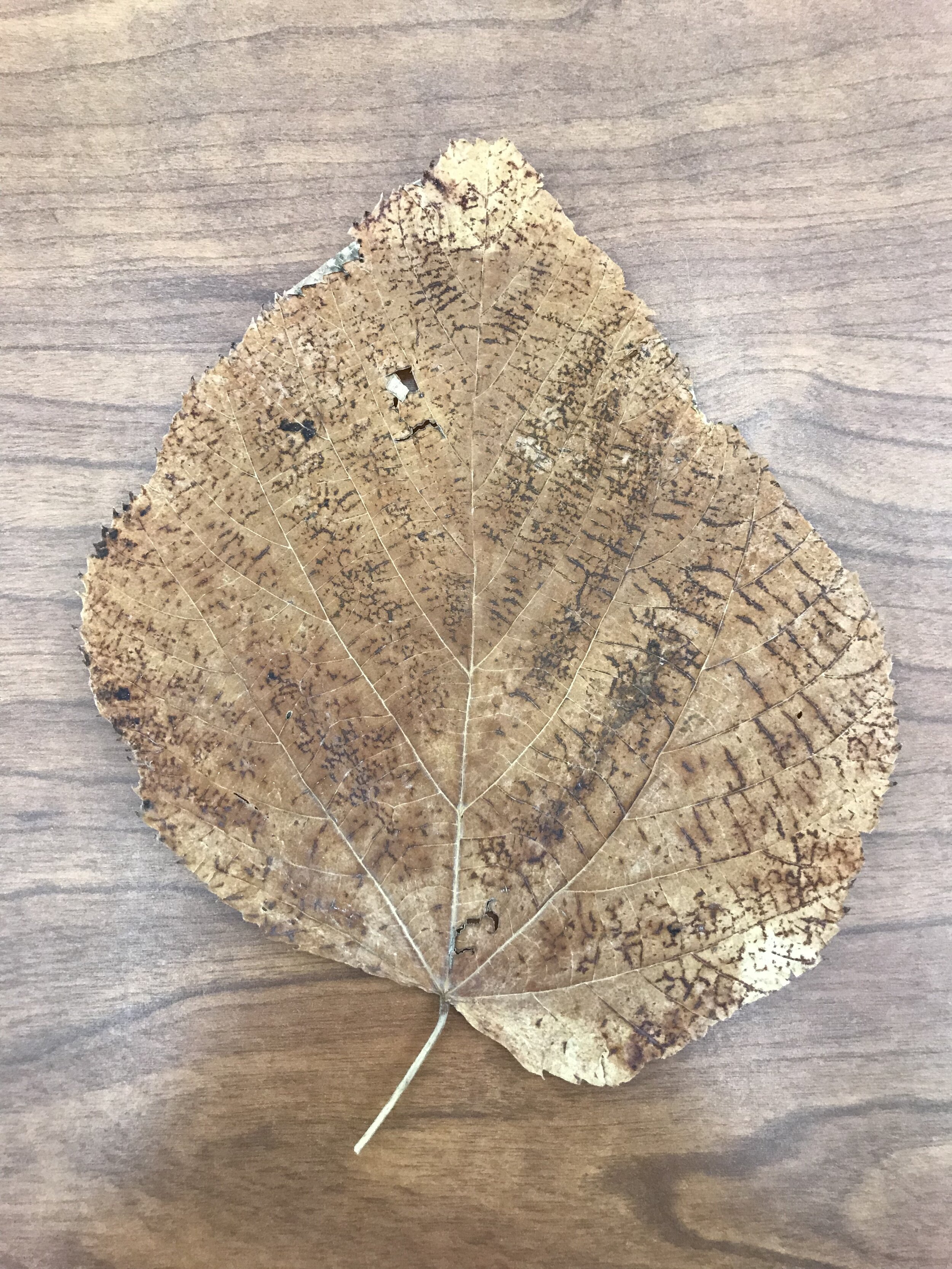

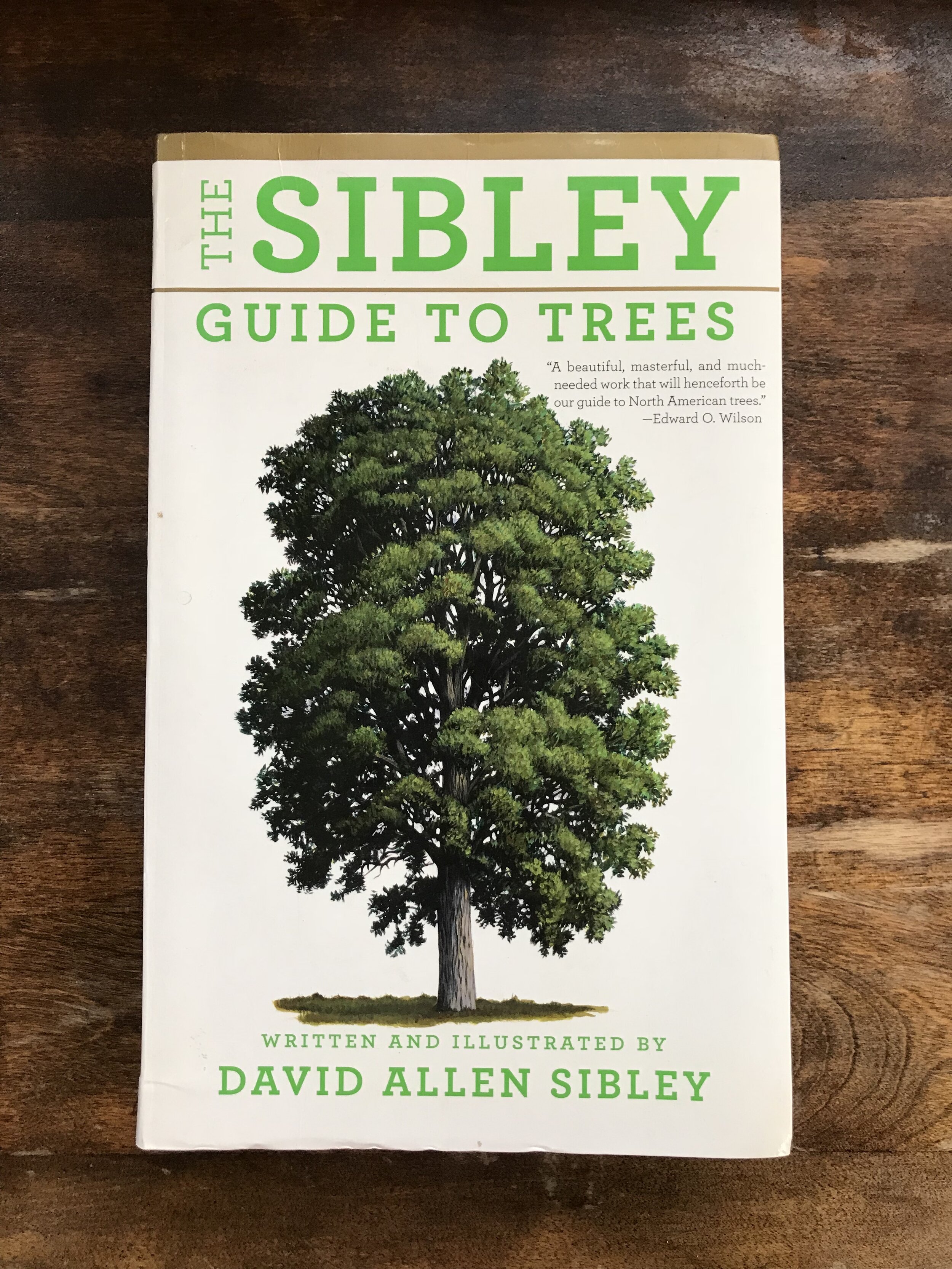

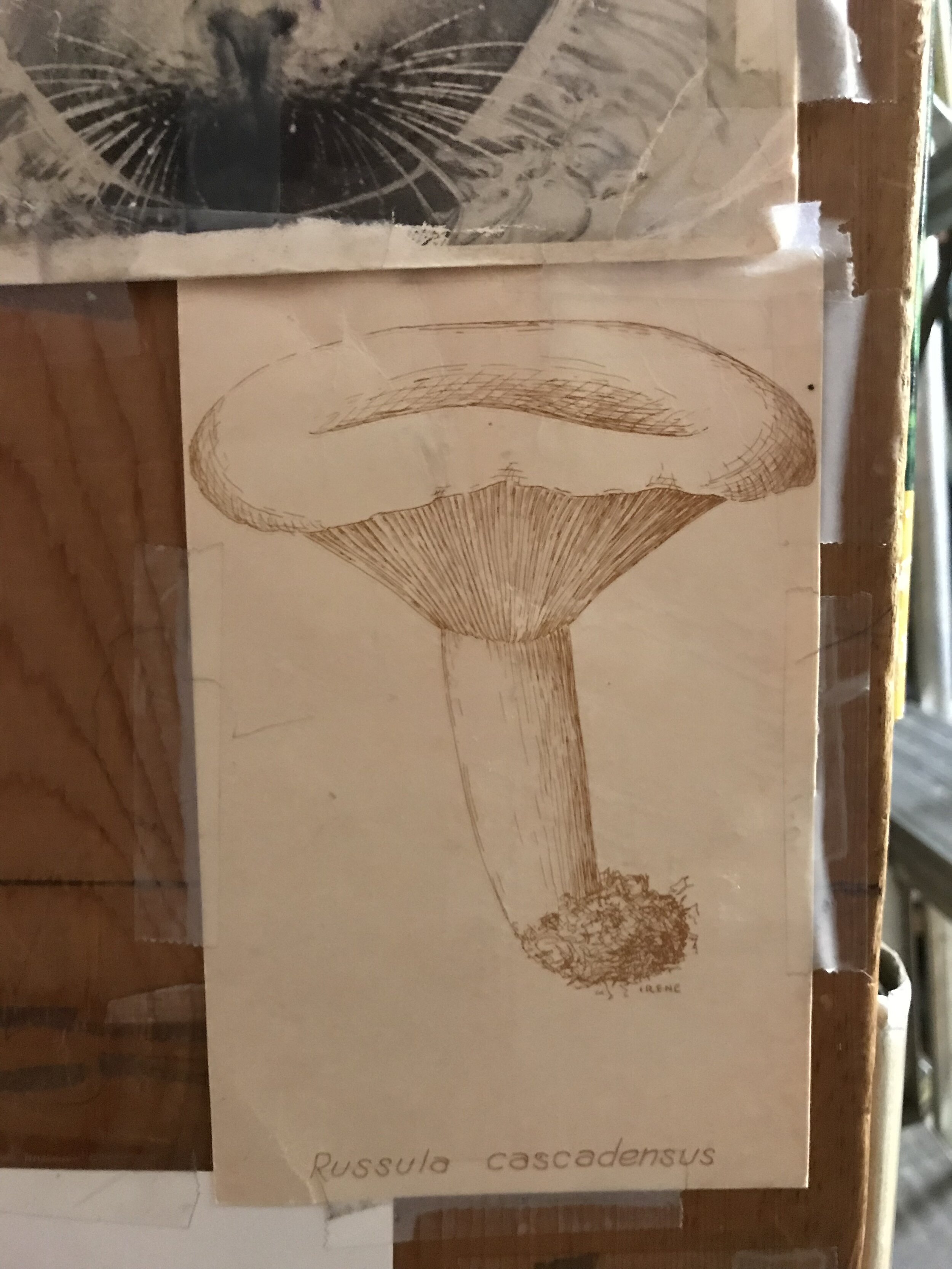

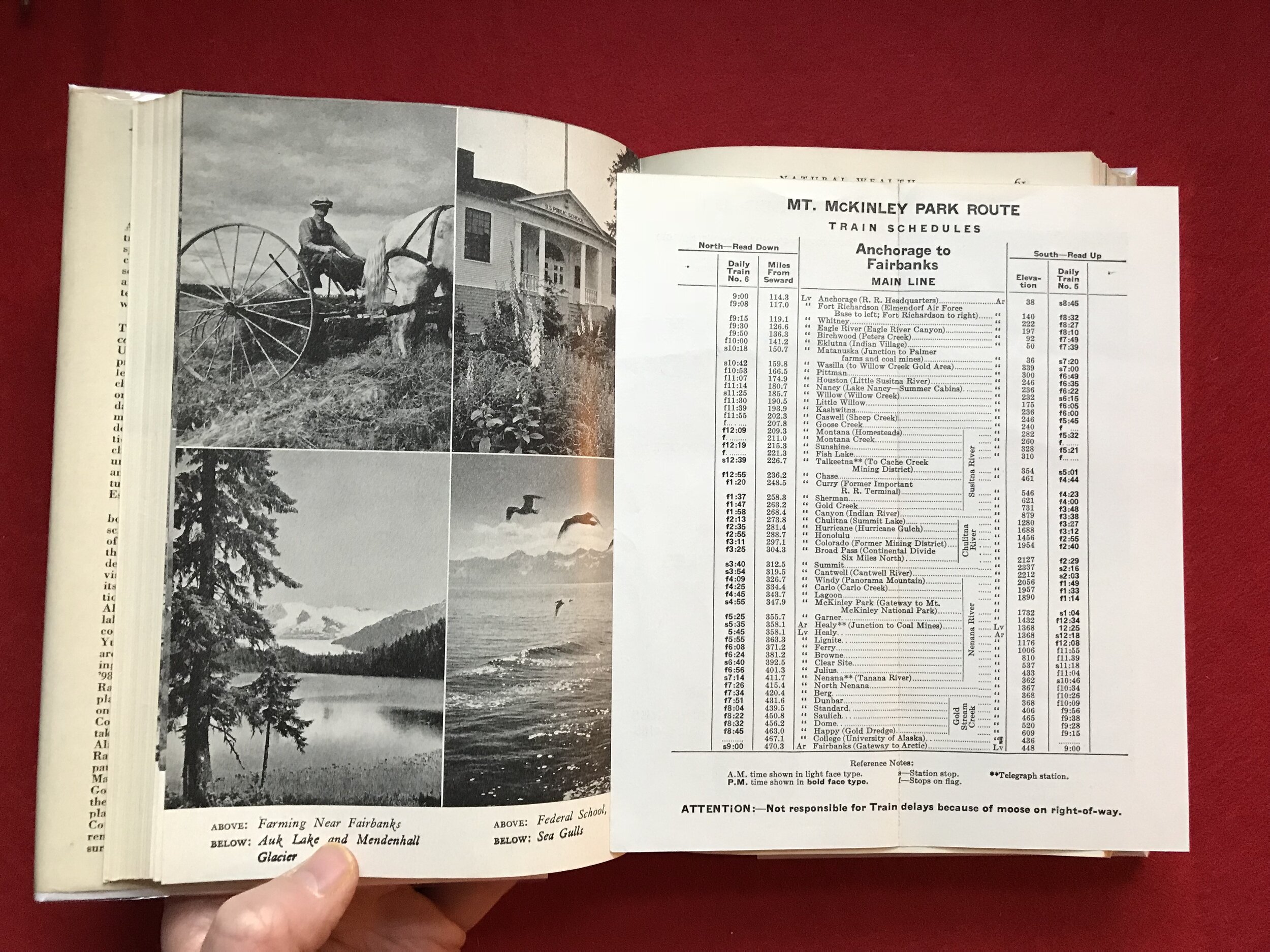

Initially, there were the field guides. As a hiker, amateur naturalist, and a book collector, I have amassed a sizable collection of these handy books. Within the first few minutes of browsing, I already found pressed leaves, receipts, planting guides, and notes from previous owners. Opening the Sibley Guide to Trees to the page where it naturally parted brought me to a large American chestnut leaf marking the page for...the American chestnut. Considered together, the capsule and its contents made it easy to make deductions about this insertion; namely, that someone had hunted down and found an extremely uncommon species of tree. While I know not with whom or with what, I felt a connection to a past. As I continued to weed through the plant, wildflower, and mushroom guides, I had also recovered different specimens I, myself, had saved and forgotten. Aided by the two now-related objects — the host (the book) and its guest (the insertion) — my involuntary, Proustian memory kicked in and brought me back to a specific place and time; a hike in this state park, a walk with my friend.

VII.

I was seven when my grandpa died. His death and the surrounding sorrow was the event I remember most clearly in my childhood. Along with my grandmother, my grandpa raised six children and cared for the many grandchildren that were to come. We all loved him dearly. Painfully missing him for many years after his passing, I would often try to connect with his memory. Yet, as many of us come to discover as we age, even the most searing and unforgettable memories somehow grow hazy, their definition muddled.

When, in July of 2017, my grandmother passed away, discussion about my grandfather naturally surfaced at the funeral. As we tried to conjure up old memories, our memories were jogged and we were able to relive some of those moments. I, too, was reminded of something. I approached my mom. “Mom, didn’t we used to have that book Shoeless Joe? Wasn’t it grandpa’s favorite book?” I seemed to remember this as fact, although felt unsure if he had even read it. Either way, I wanted to read it; on the off chance he had read it, I could feel like I was sharing an experience with him. Anyway, It was family canon that my grandpa had been an extra in the movie Field of Dreams, which was based on the book — that seemed reason enough.

“Ask Jane, she’d know,” was my mom’s suggestion.

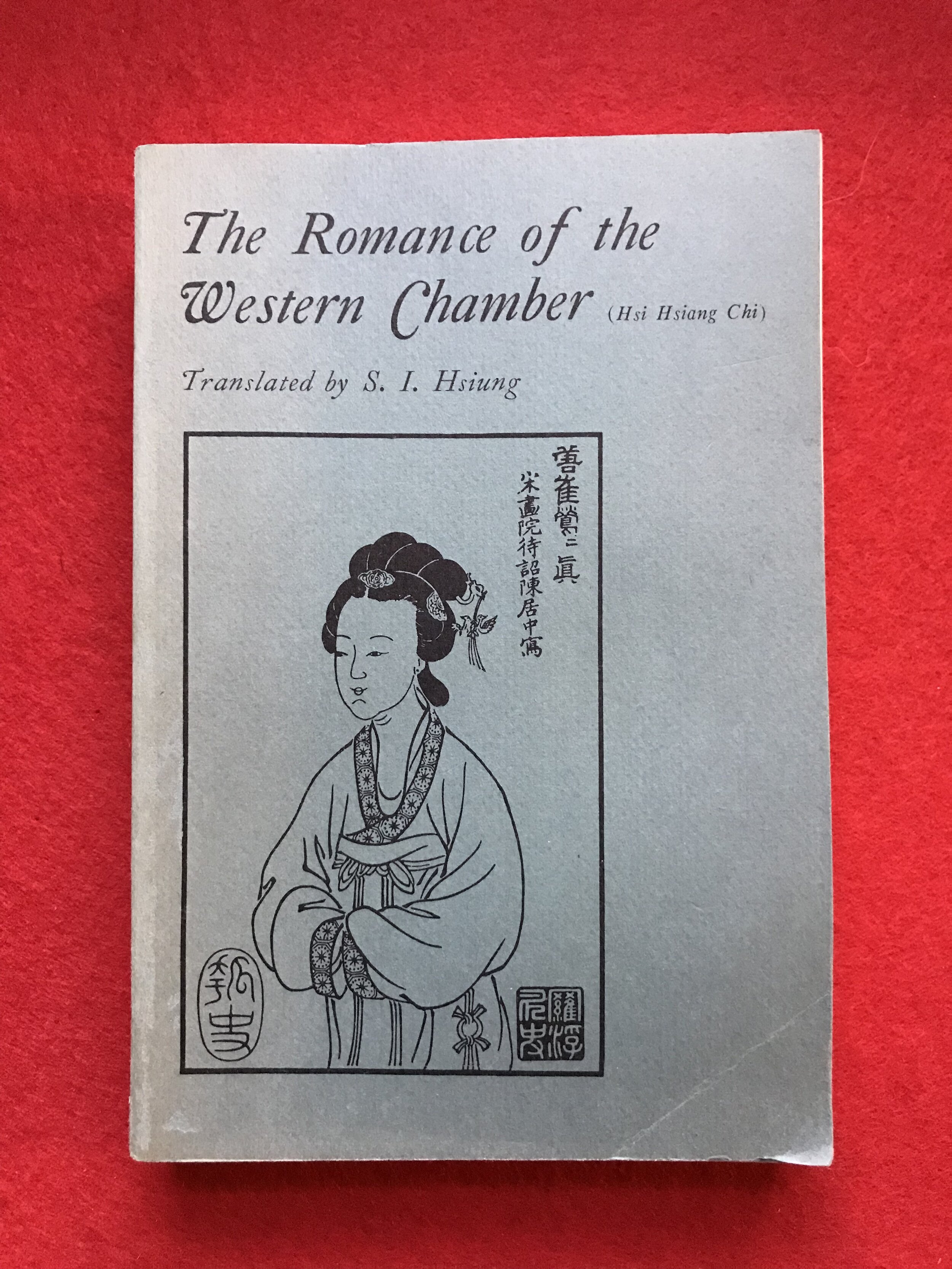

Shoeless Joe by W.P. Kinsella

I found my aunt Jane and asked her. “Was Shoeless Joe grandpa’s favorite book?” She answered, “I don’t remember...you know, I don’t think so. Grandpa didn’t read that much.” After asking a few other family members and getting a few confused responses, I felt discouraged. Later in the day, my mom, sisters, and my girlfriend went to a local Christian retreat where my grandparents had both come to find comfort. As we were walking the grounds, I went up to my mom and relayed to her what I had discovered about Shoeless Joe: it was unlikely that he had read it, much less that it had been his favorite book, I told her. I was sure, though, that I had seen the softcover on our bookshelf growing up and remembered the name of the author, W.P. Kinsella, “Can you just keep an eye out for it, I’d still like to read it,” I asked, soon after forgetting my request.

A number of months passed before my mom came to visit me in Madison. She brought with her a special gift: Shoeless Joe by W.P. Consella. She had found the old copy and it was exactly as I had remembered it. It was in crisp, perfect shape, as if never read, and I protected it as if it were a secular Shroud of Turin. I placed it in a safe place, eager to read it, but only at a self-appointed hour, appropriate for a book with the value I had projected onto it.

A few more weeks had passed, and on a particularly relaxed night, I isolated myself in a little nook and turned on the lamp to start reading Shoeless Joe. Opening the book for the first time, I noticed an inscription on the inside of the front cover. It was in my mother’s handwriting. The words were a heartfelt dedication to the book’s receiver, my grandfather. Above the inscription was the date. I did the math: the date was just weeks before he would pass away. I felt my mom’s sentiment and re-lived the pain so deeply that I felt disoriented. Dedicated to not letting this moment or opportunity pass, I started reading the story. I felt a presence that I, for so many years, had so earnestly tried to channel: I was sharing an experience with my grandpa, again. A few minutes passed in this imperfect yet profound reunion with my grandpa.

The story, written in a meditative prose, passed by quickly. Events in the story had suddenly become very real; however fictional Kinsella’s account, the story, printed right there on the page, was real. I was positioning my reflections of the story alongside my grandpa’s; he read these same passages...what did he think? He was alive, in a way, in some ways more authentically alive than in my earlier, albeit sharper memories. Those earlier memories, after all, were of a young grandchild’s grandpa - and children’s images of their grandfather do not have the points of view of a fully-grown adult. These new connections were not just of “grandpa,” but of Tom Strong, a real human who read and thought and reflected, just as I was then doing.

As I turned to page 14, my heart sank. Wedged between the pages was a torn-out section of a page from an 1980’s home-improvement catalog. He had apparently gone no further, and I too, would not be able to go further, at least with him along.

As time has elapsed since this experience, and since I began this project, I’ve contemplated the connections between text, books, their readers and their users. A few things have come to mind:

a reader shares something intimate with the author, just as the author shares something intimate with the reader; they are both aware of it but cannot fully define it

a book’s user also shares something with the book’s producers, and vice-versa; often the separate parties are unaware of each other

Two readers of the same book also share something intimate; often they are unaware, other times they are wholly aware

And one step further:

Two users of the same book share something; often they are unaware, other times they are wholly aware

My mother’s inscription and grandfather’s bookmark had brought me to a world far distant from the author’s content; it brought me to the world of my mother, to the world of my grandfather, and to the world of the past; what was inside brought me to a world outside of the book.

+++ Below is a selection of some of my favorite finds. Further below the galleries are the works referenced in this essay as well as a few notes of thanks.

Thanks for looking.

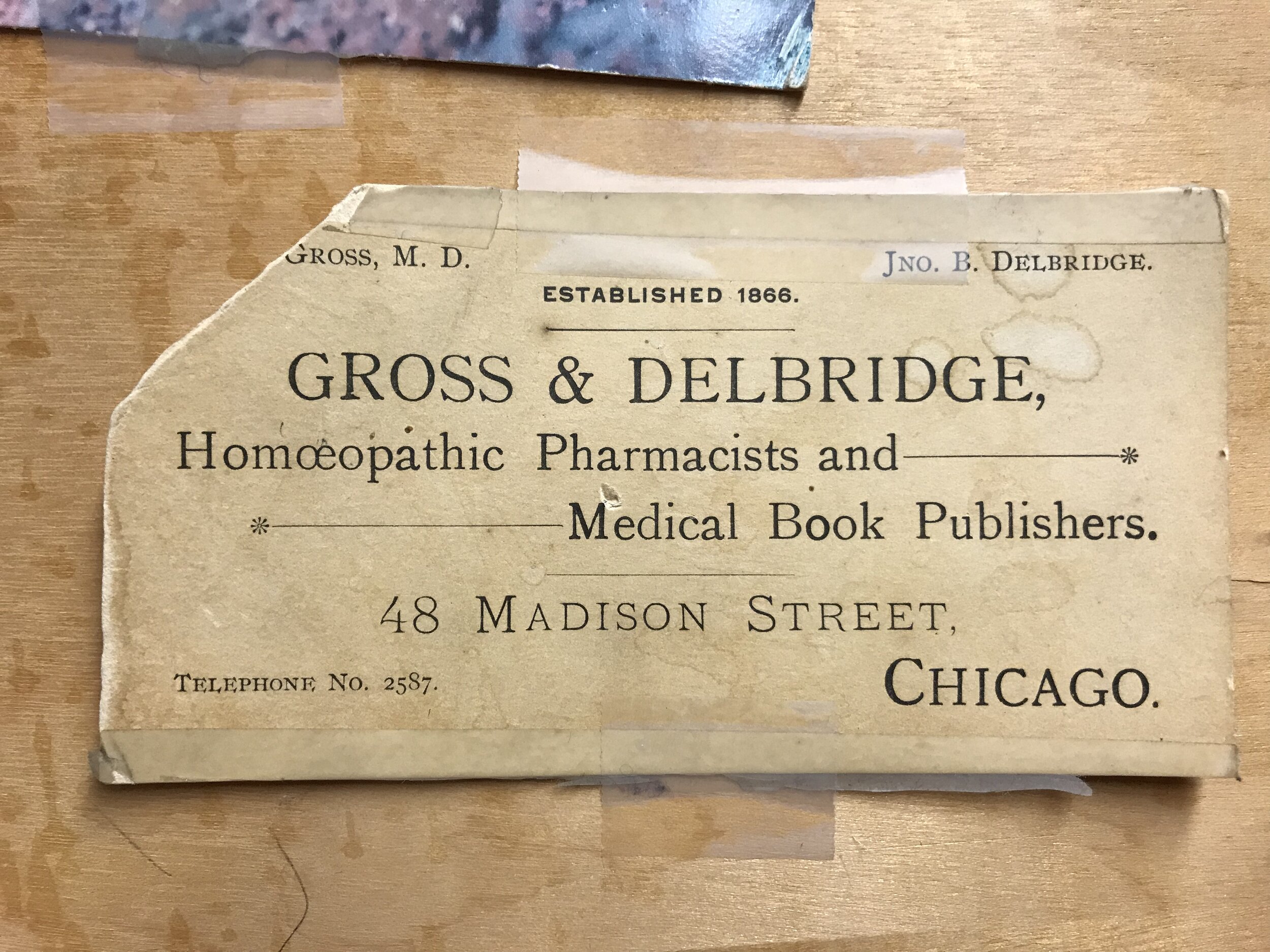

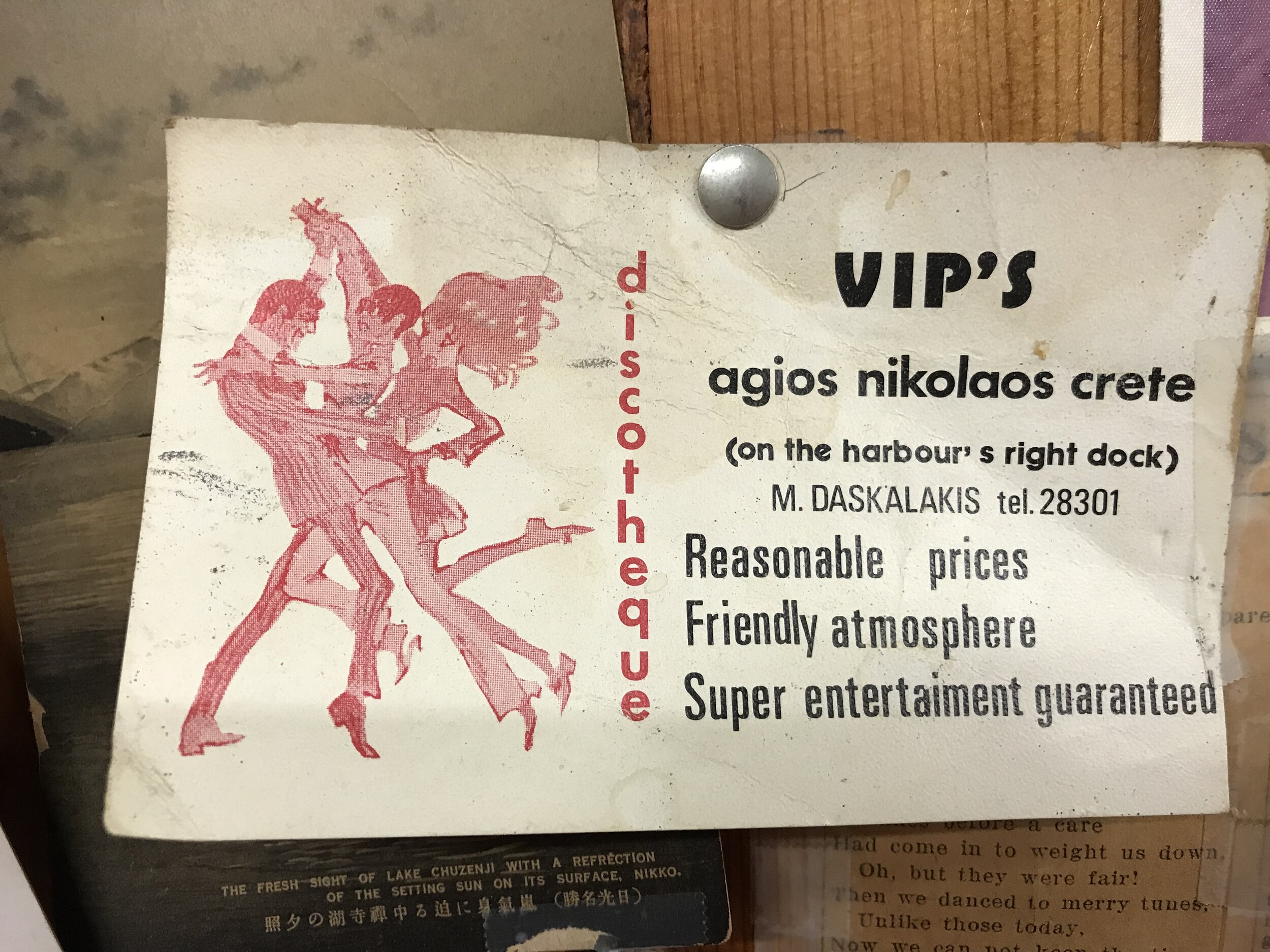

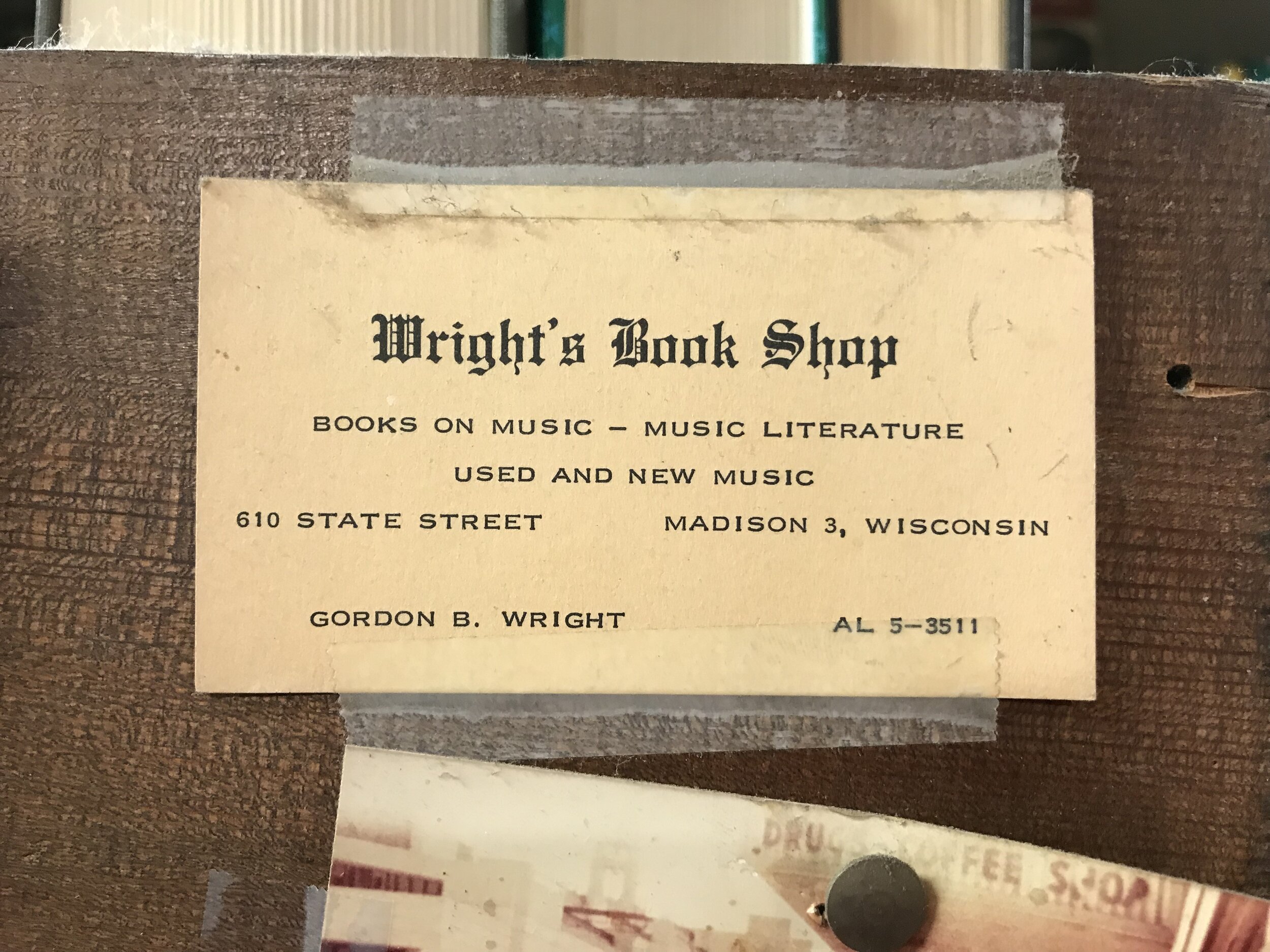

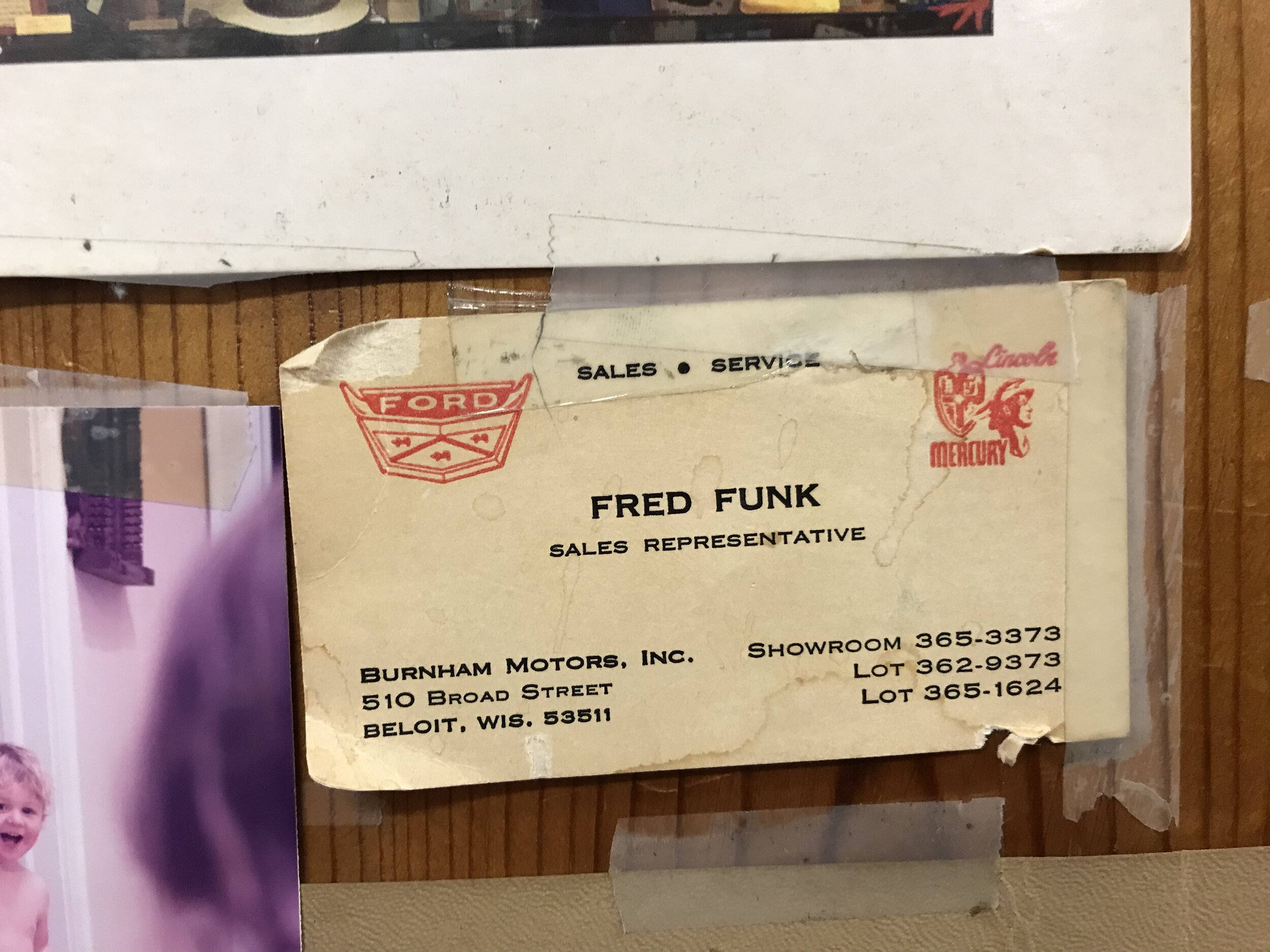

Business Cards

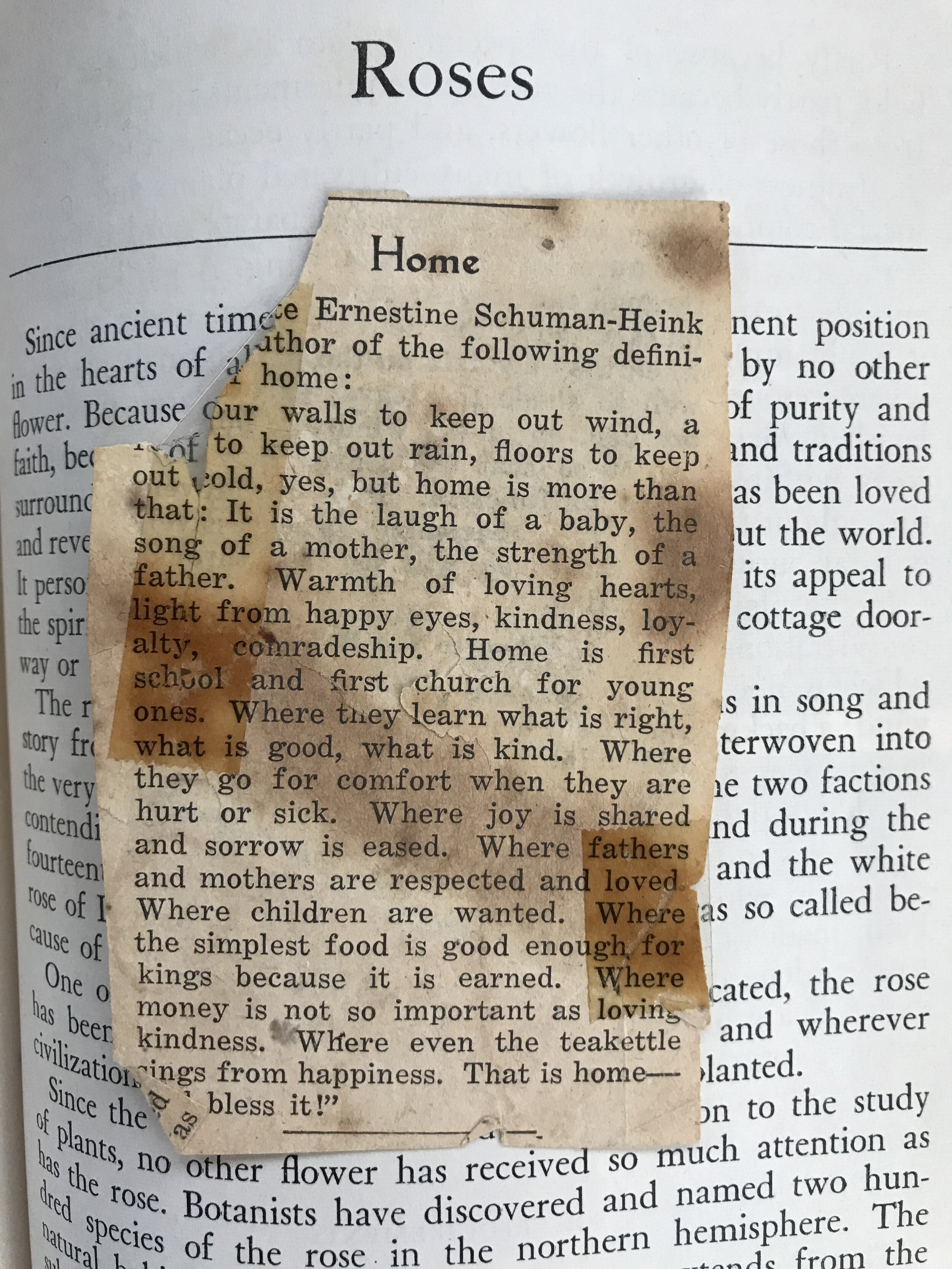

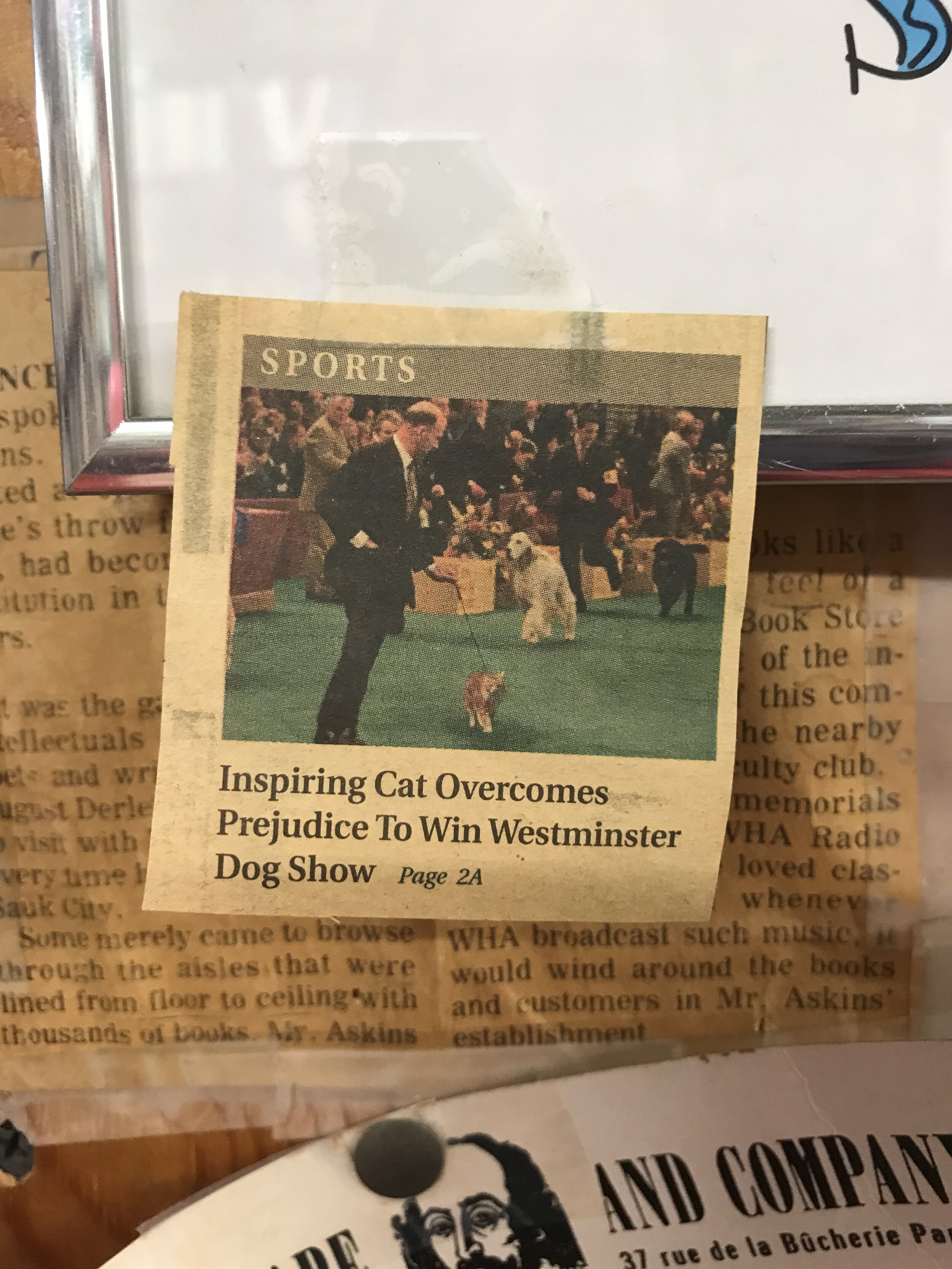

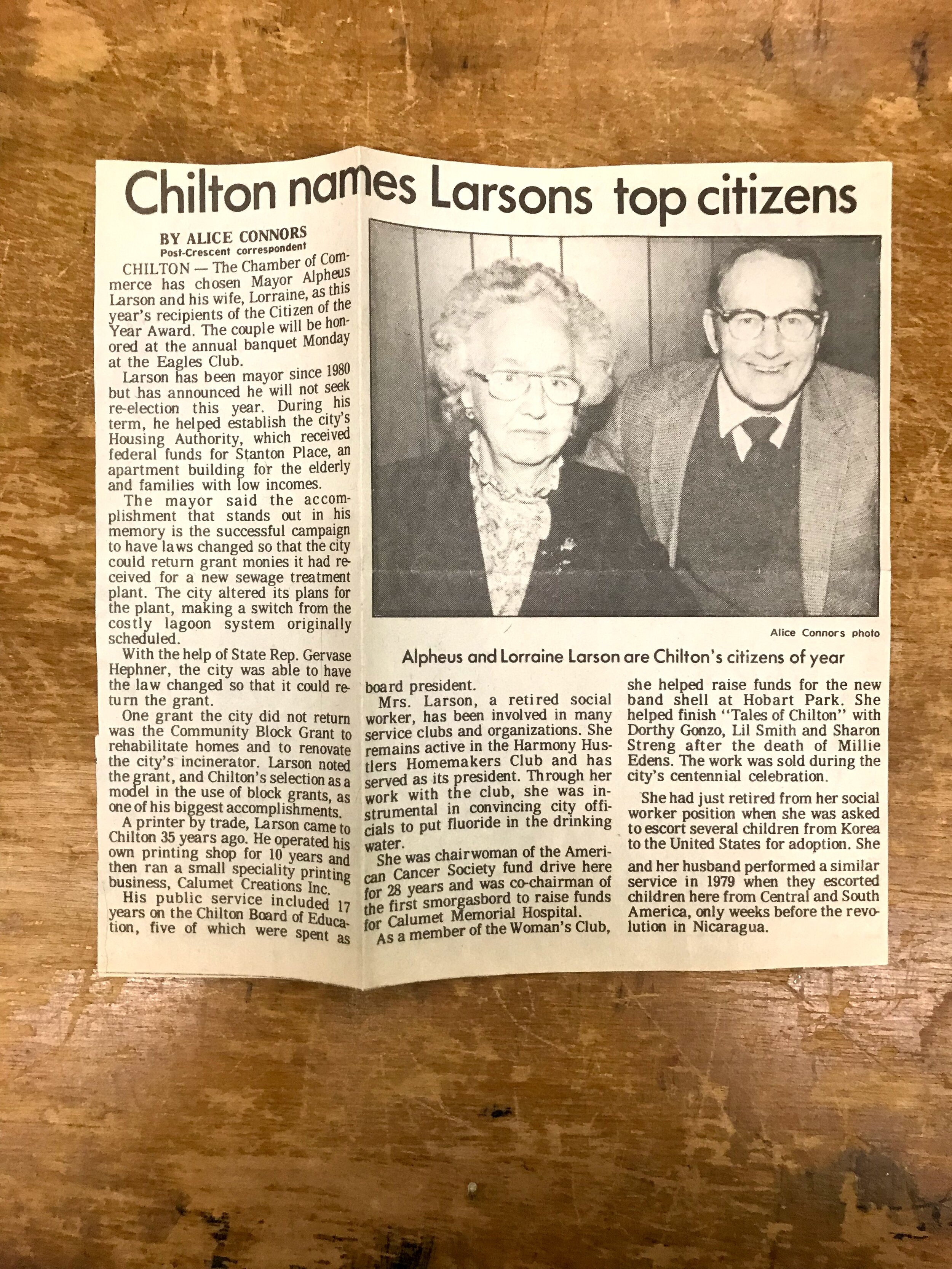

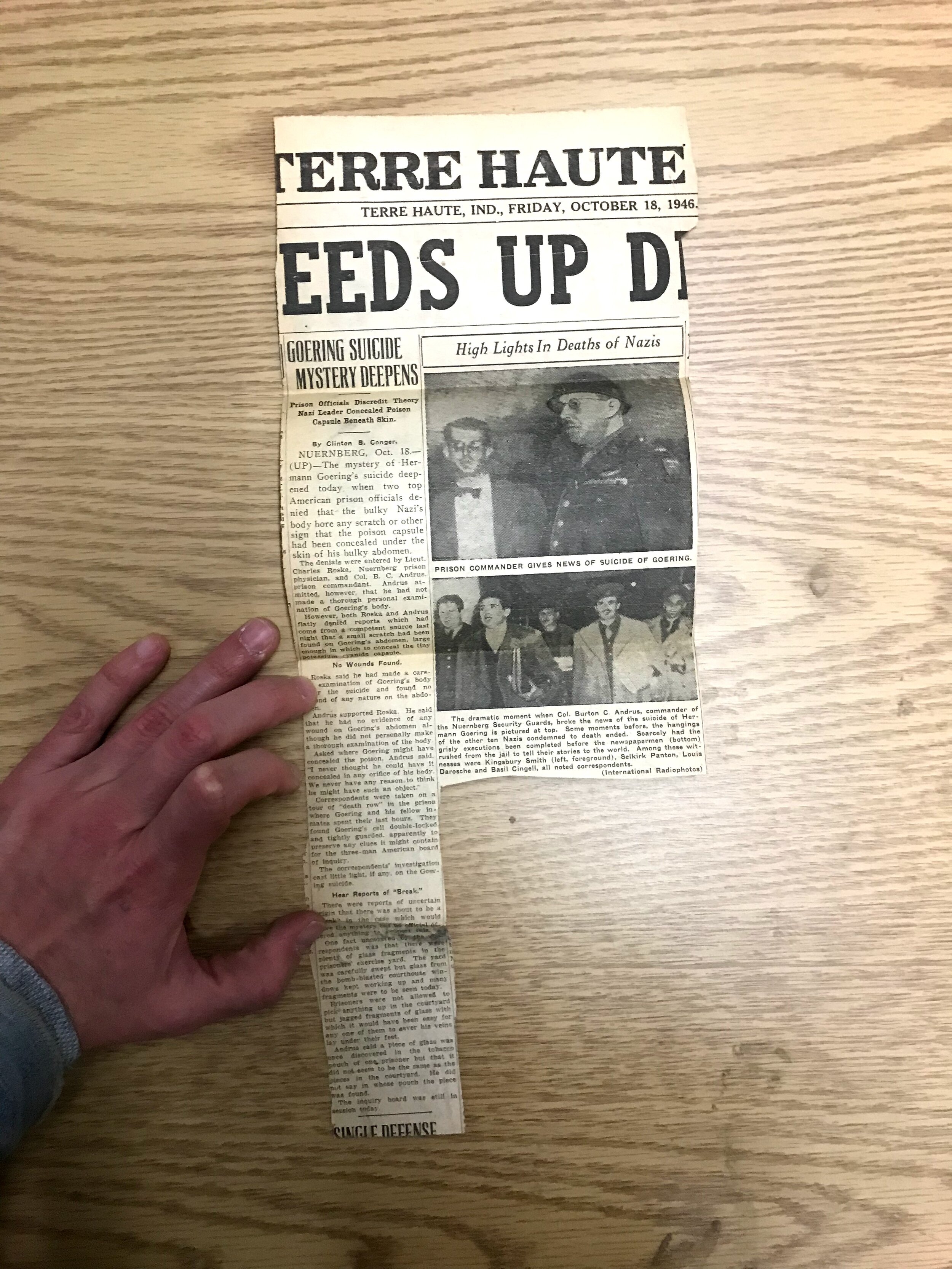

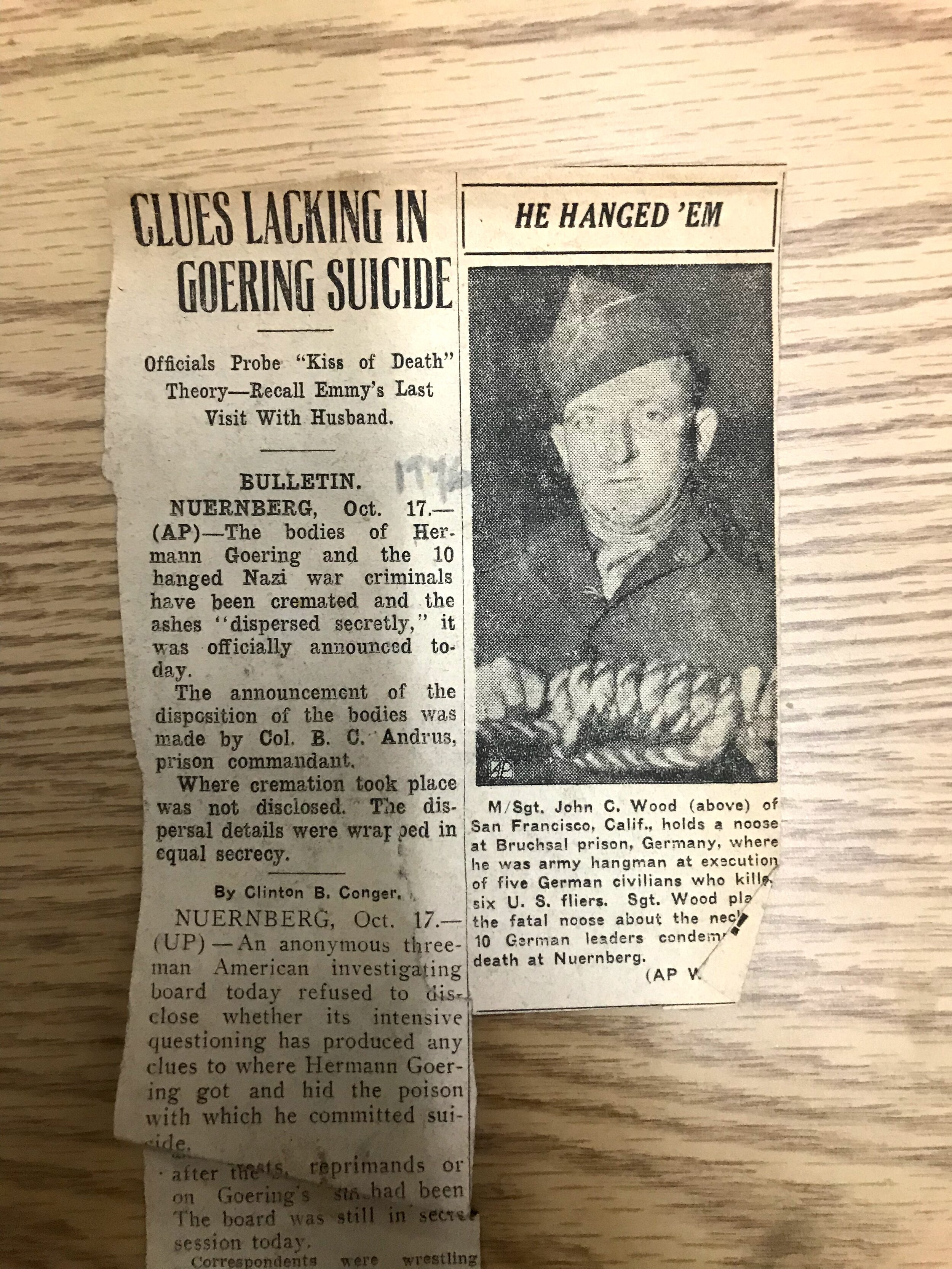

Newspaper clippings

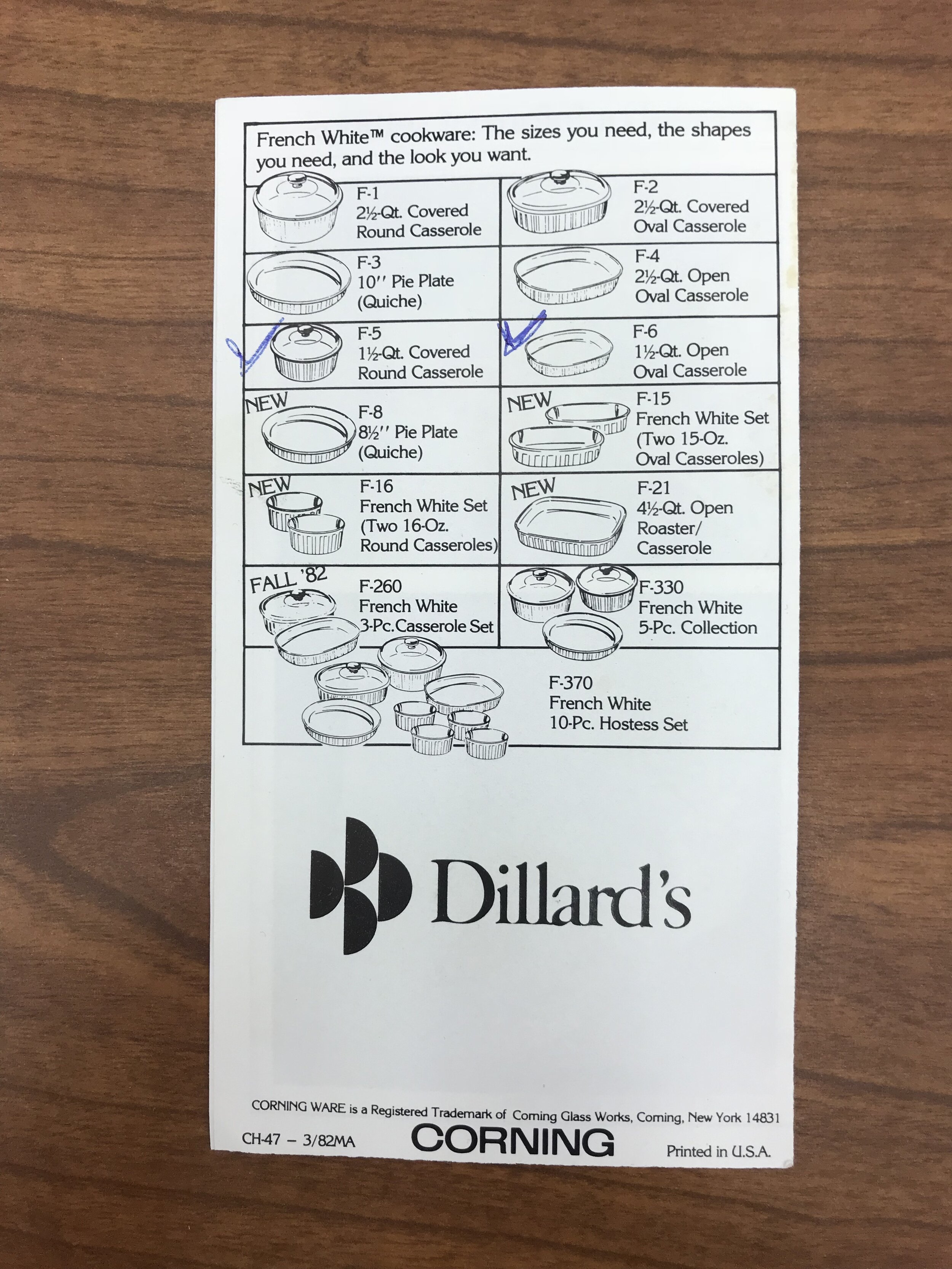

Food and related

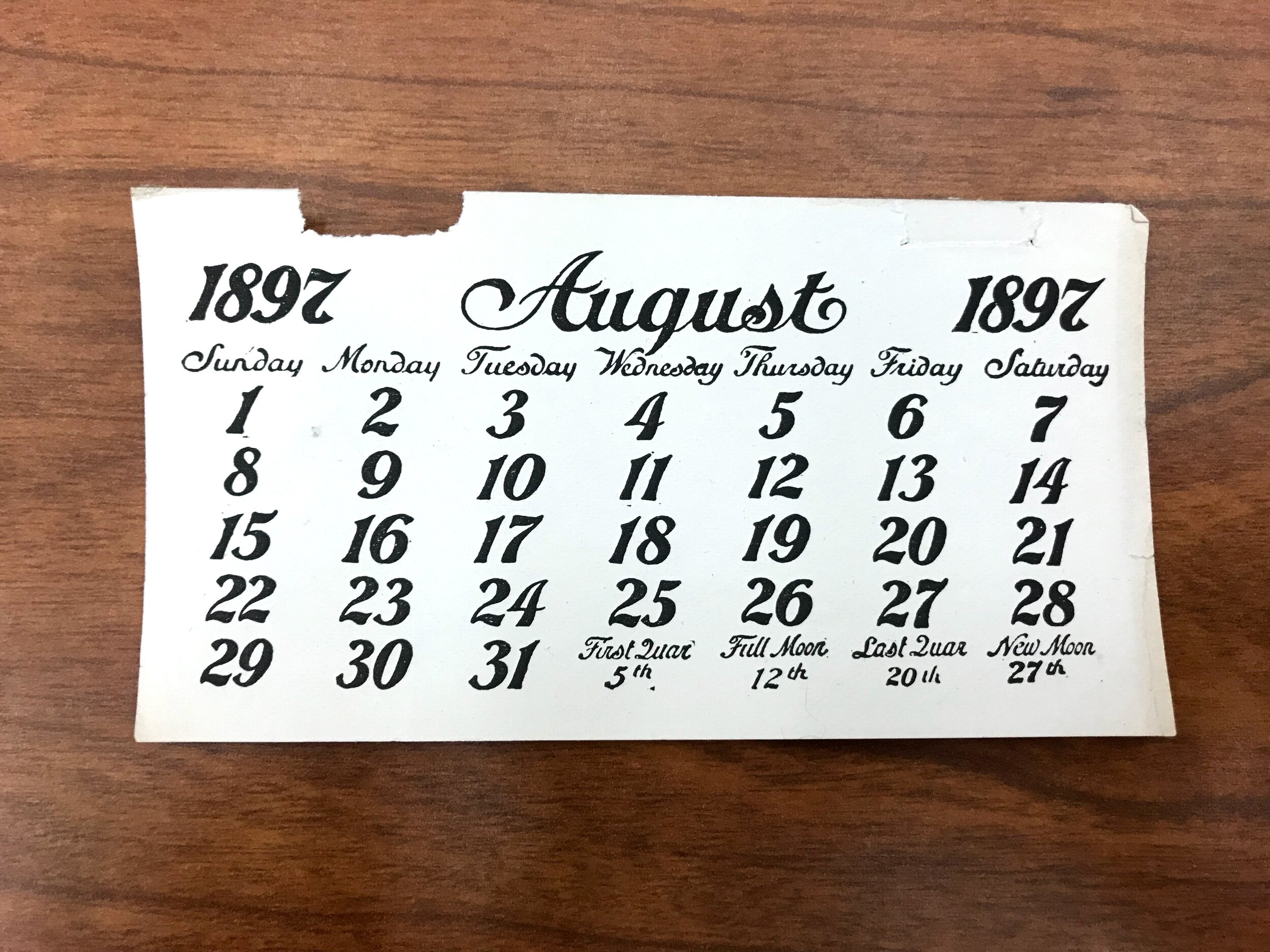

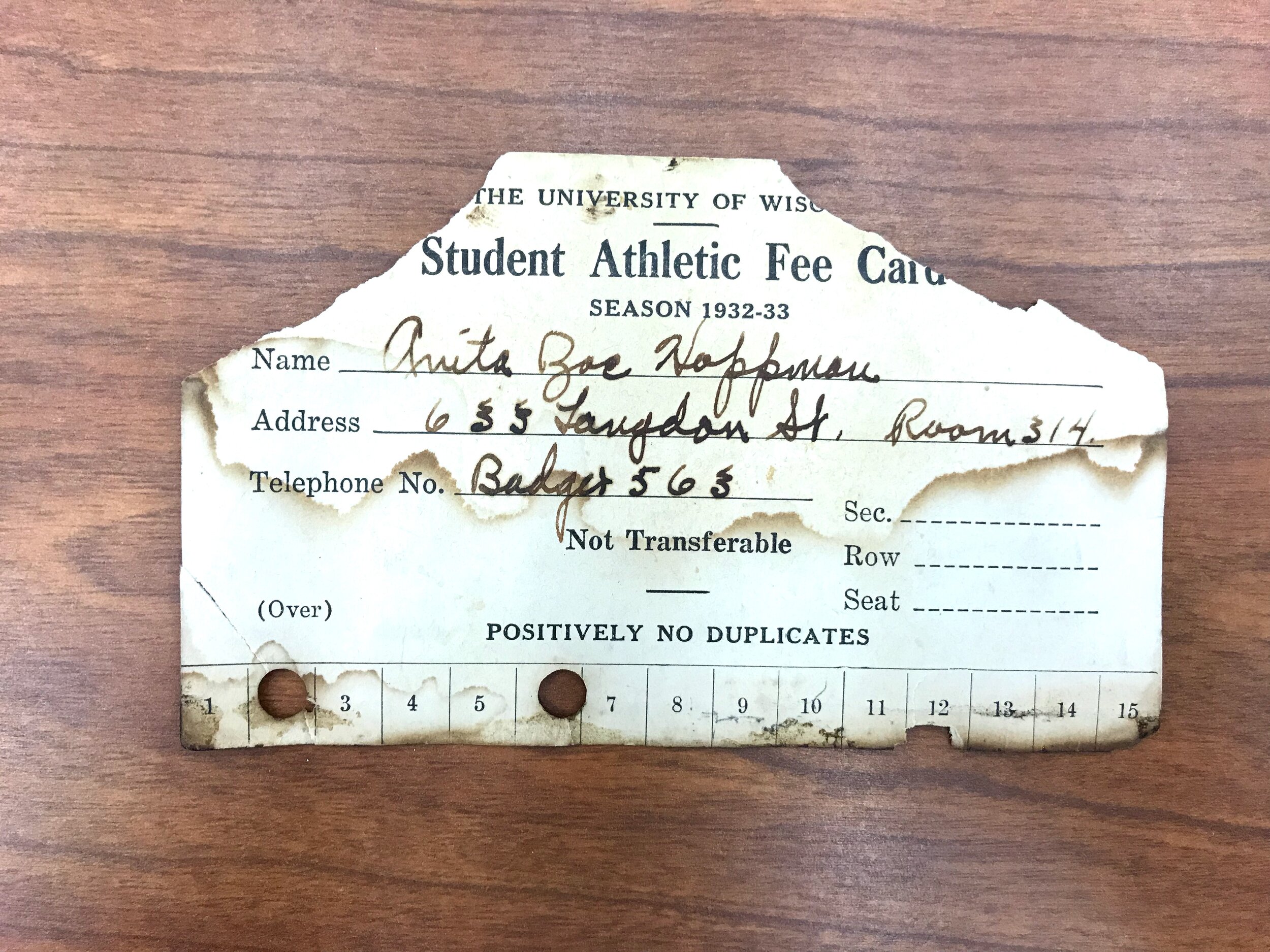

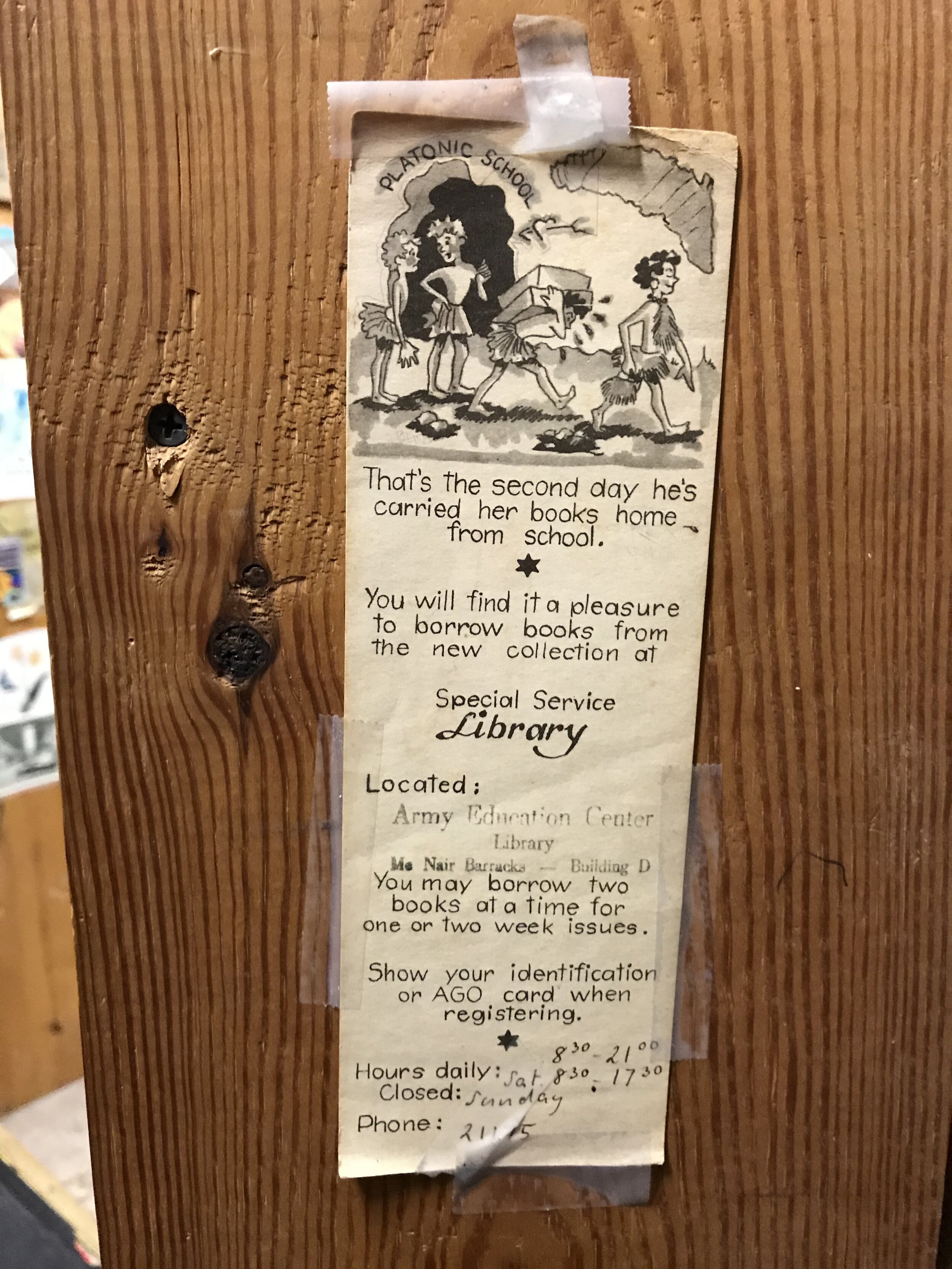

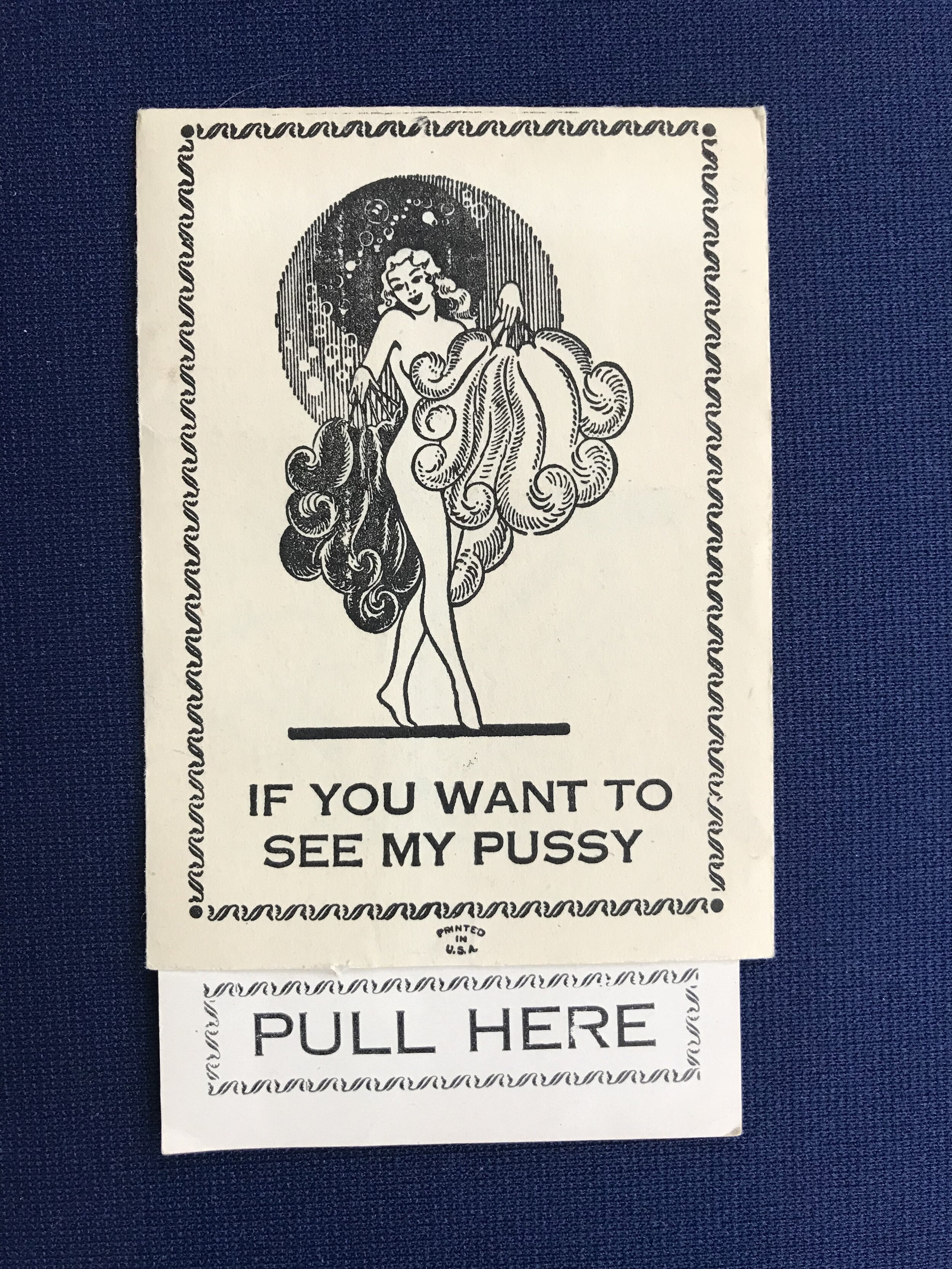

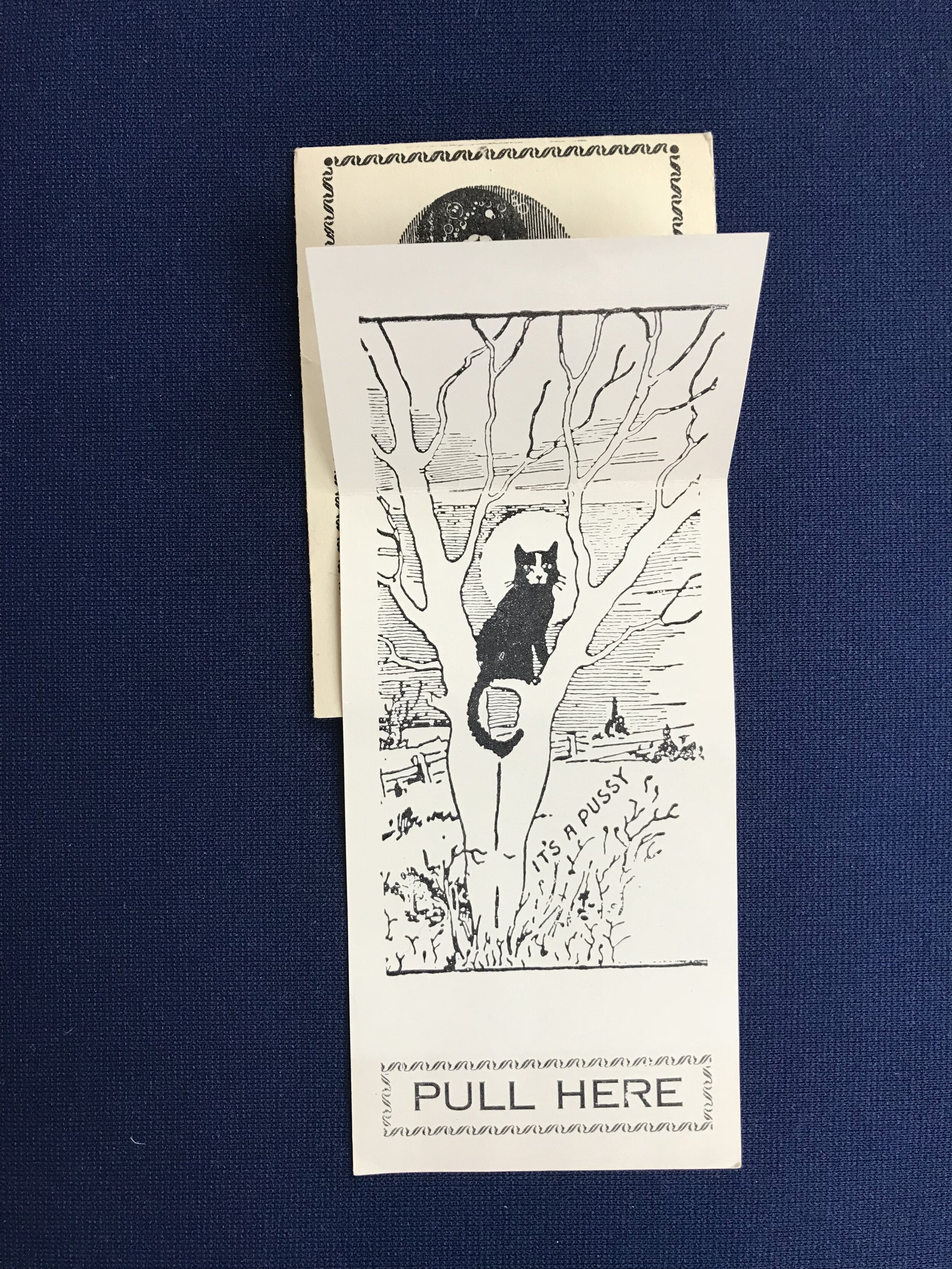

Bookmarks

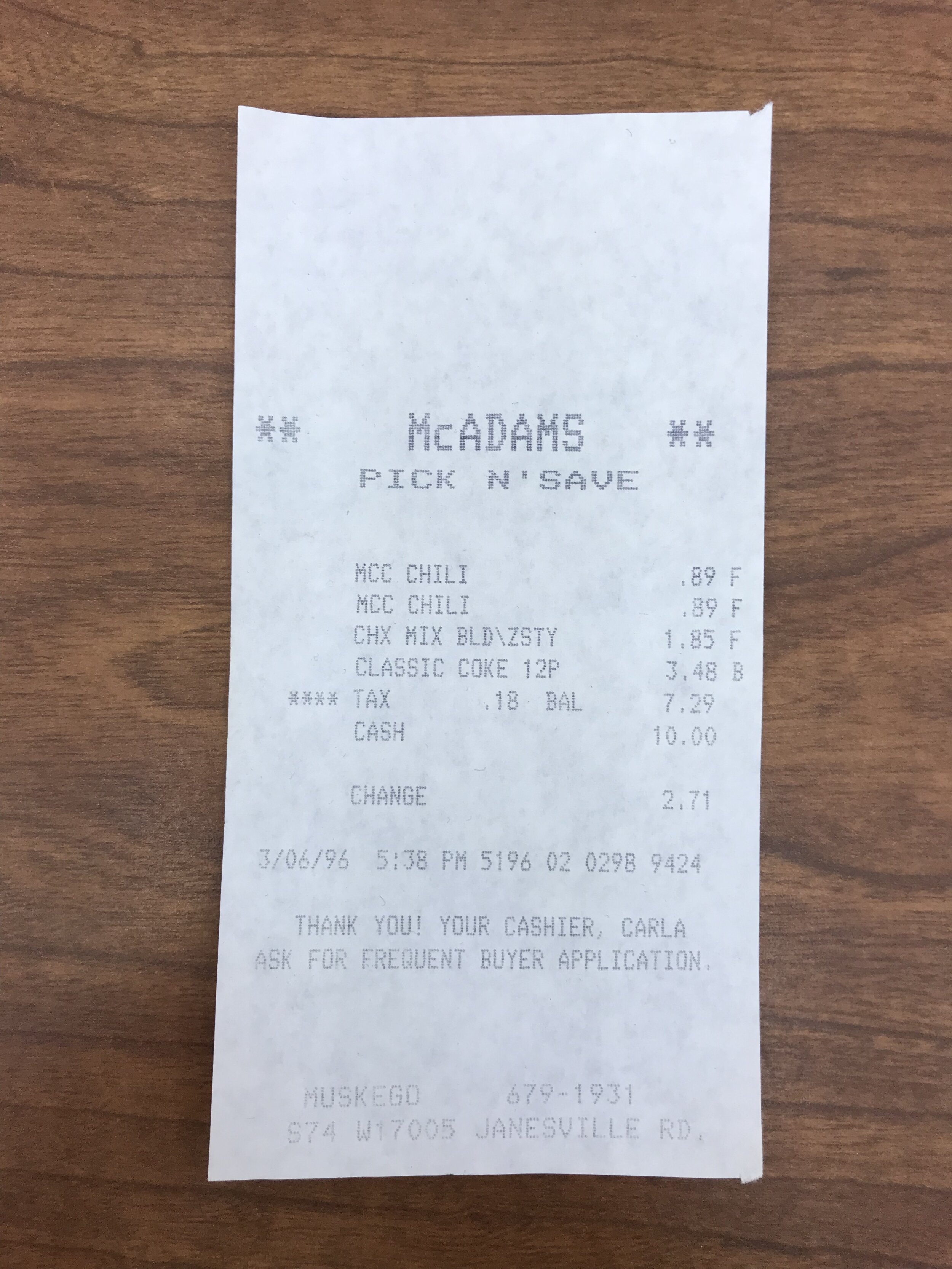

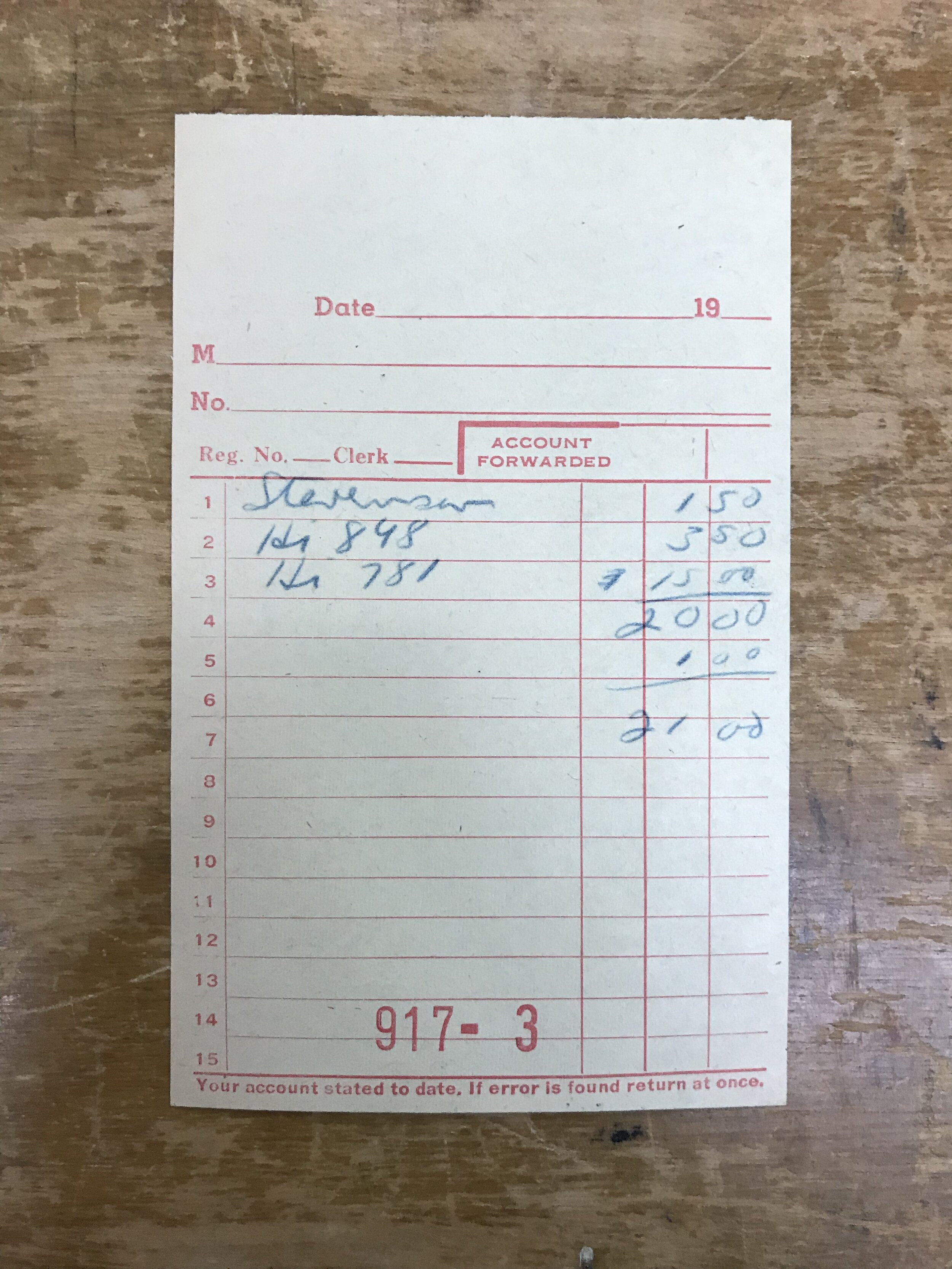

Receipts and tickets

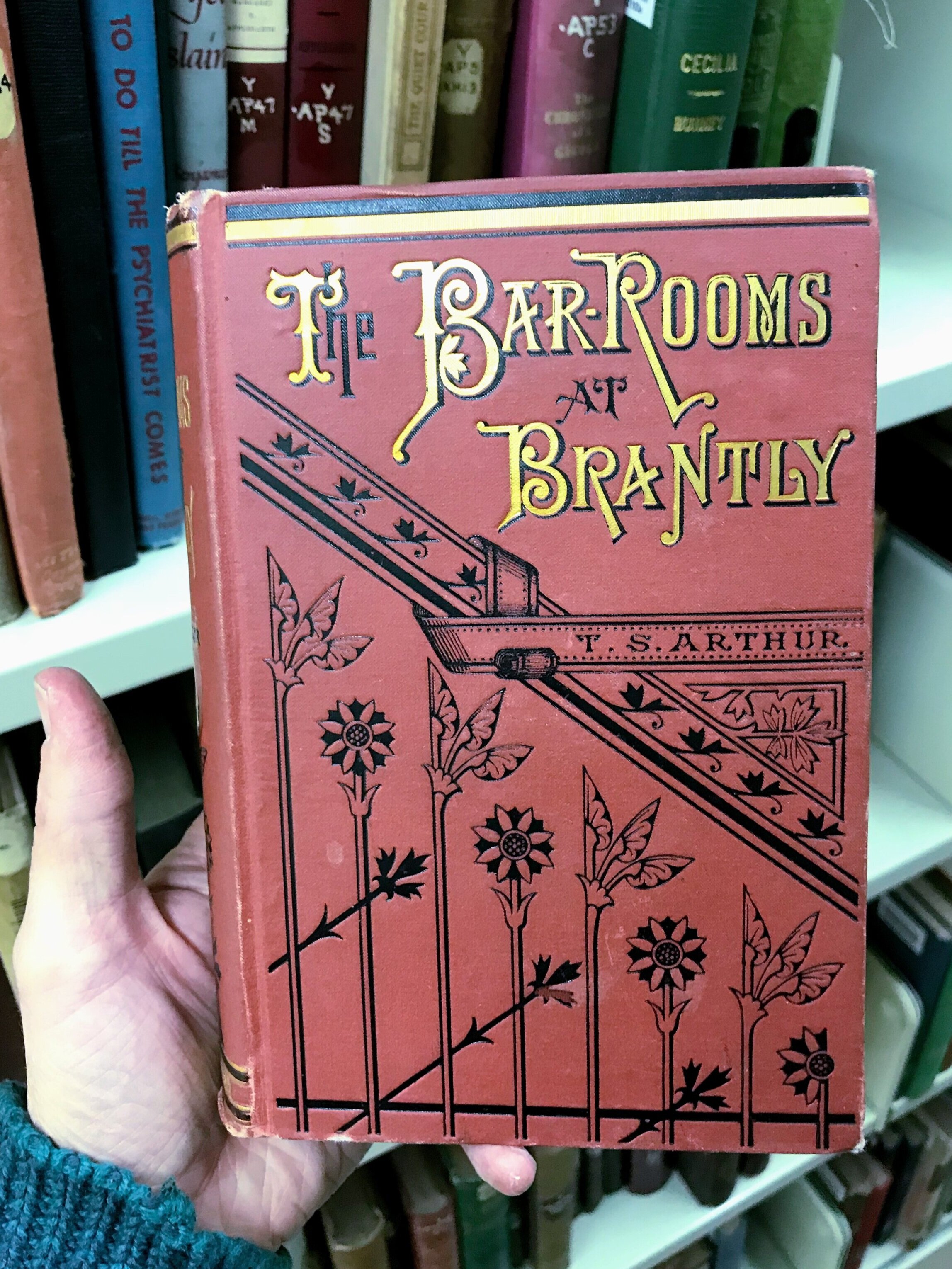

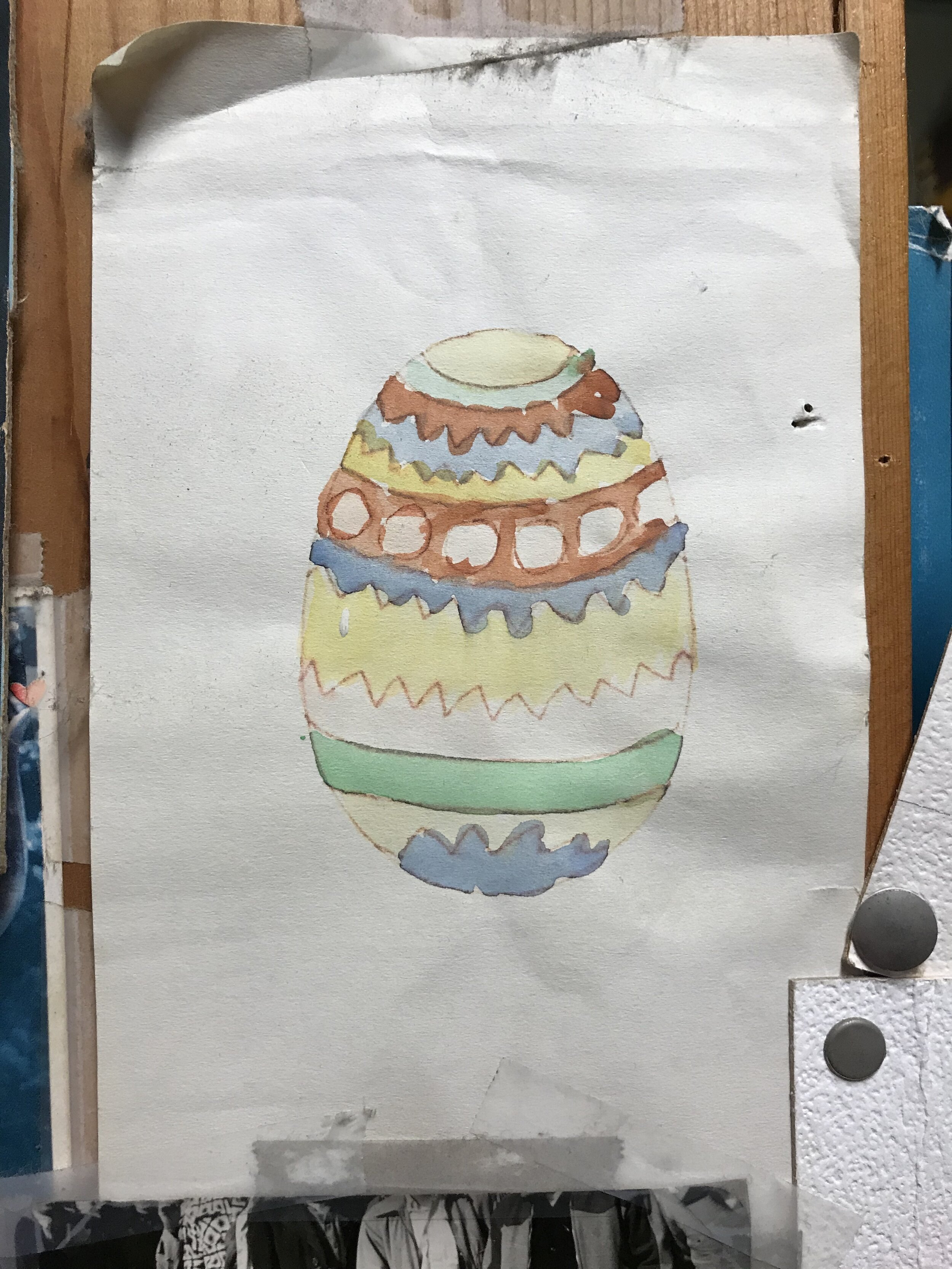

(Once) Living matter

Photographs

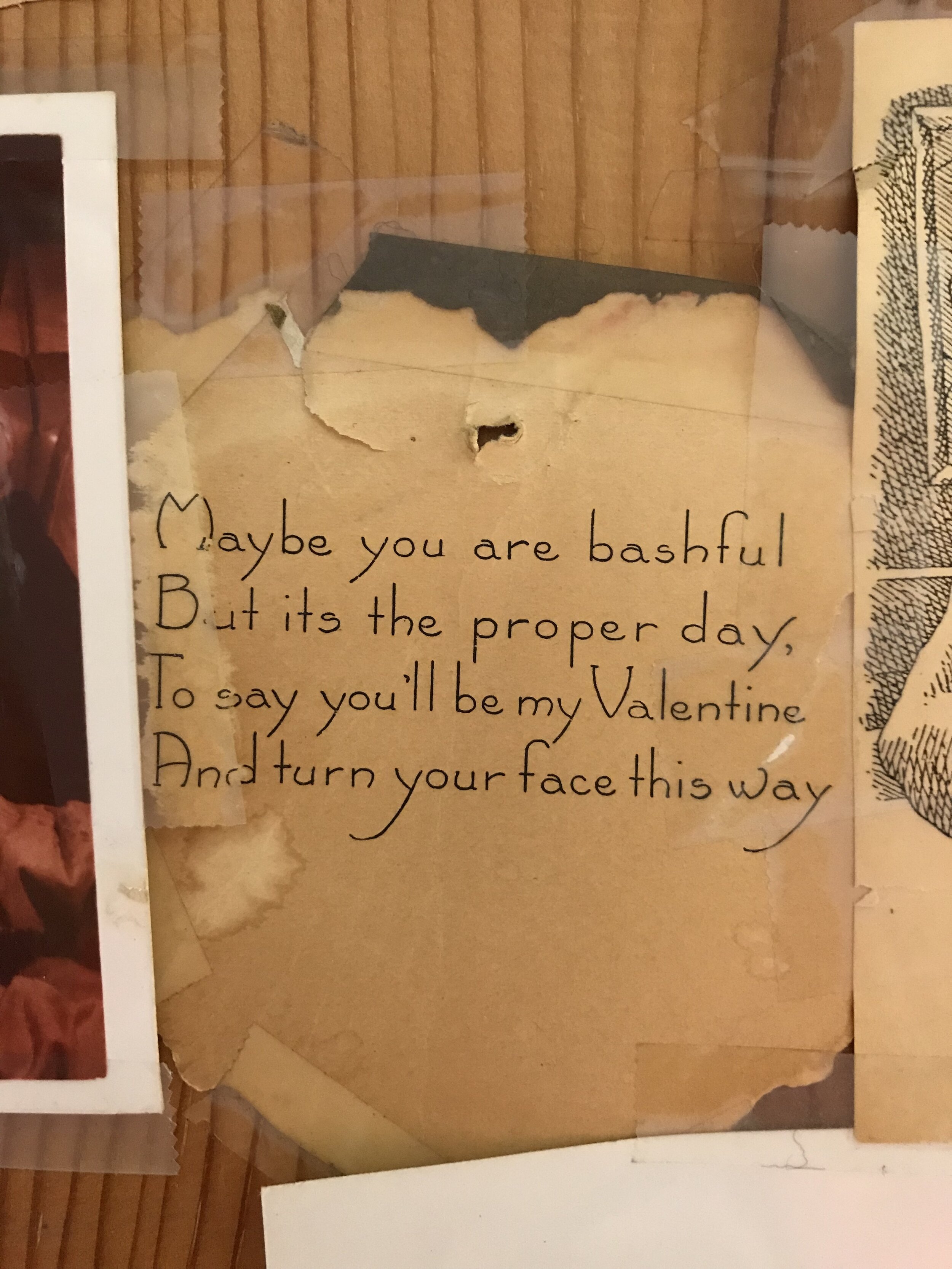

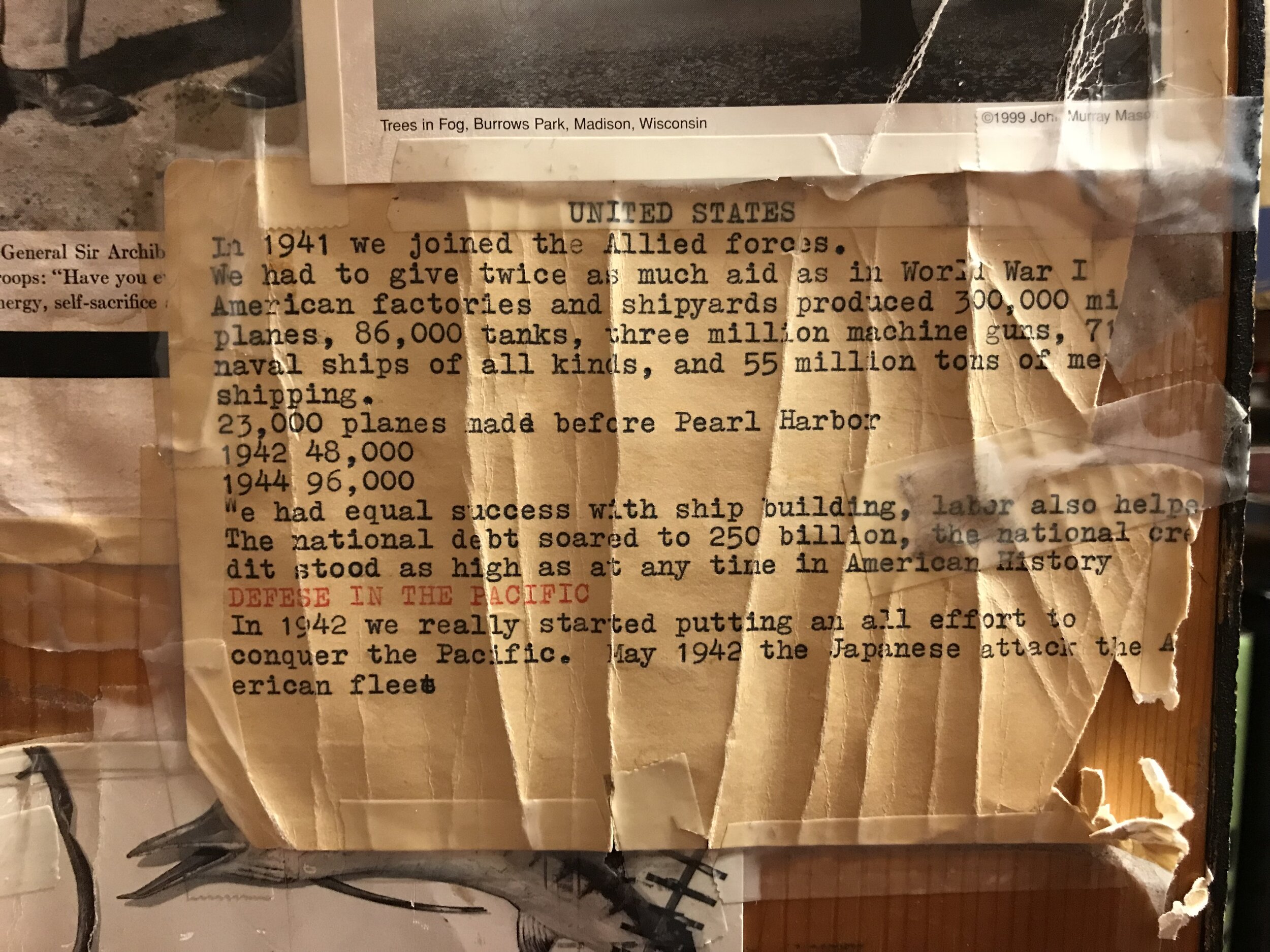

Notes

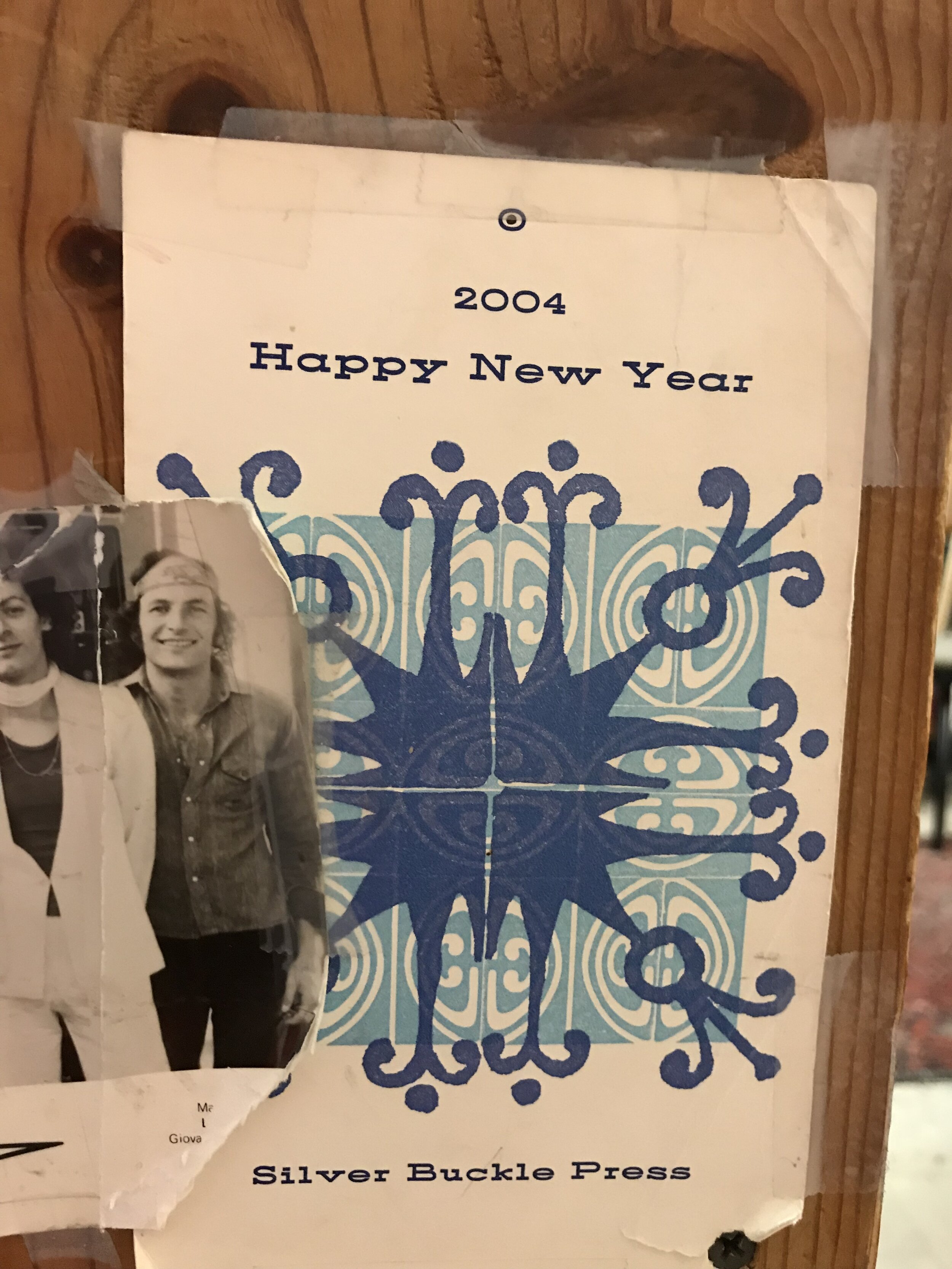

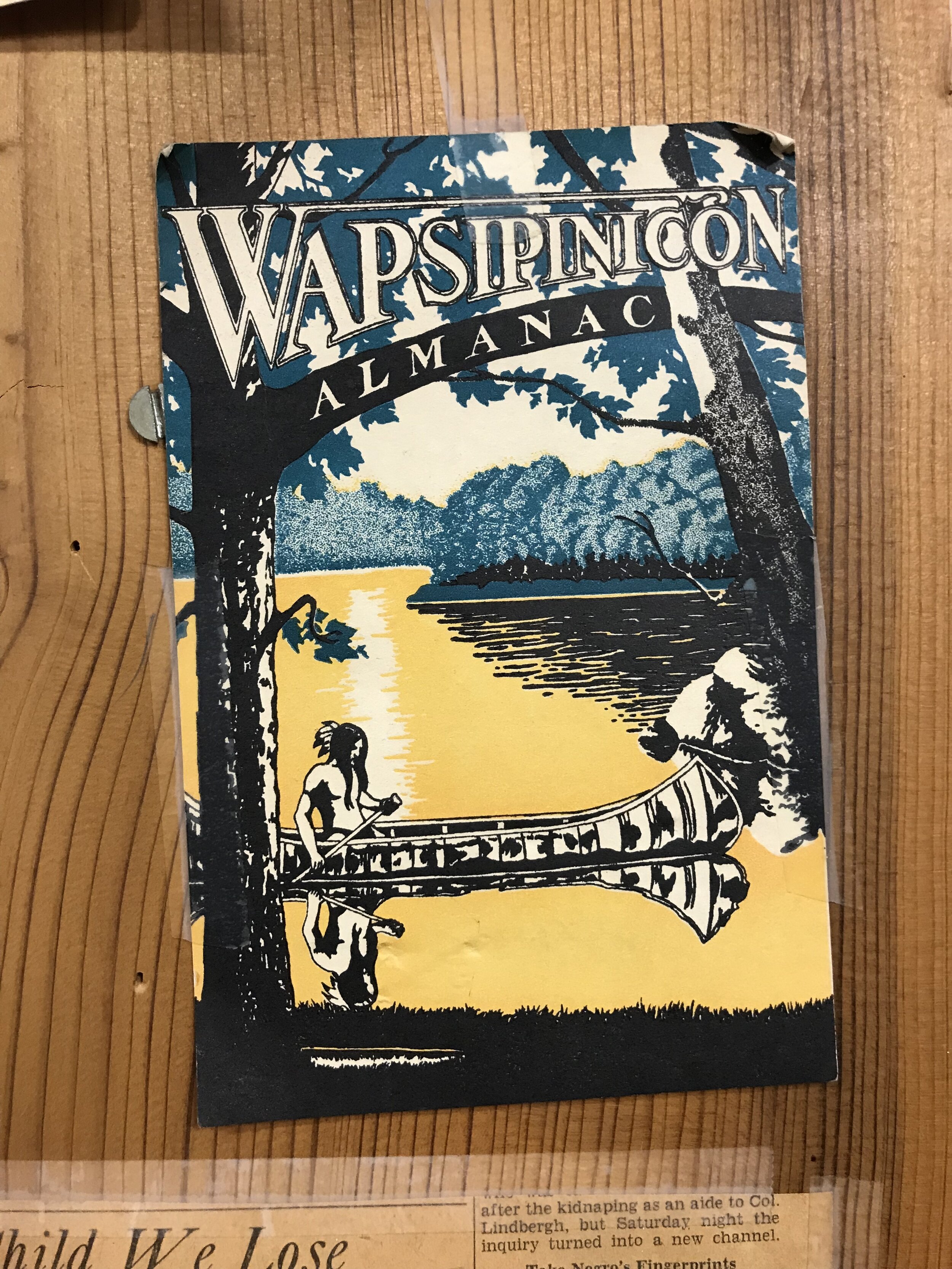

Miscellaneous

A parting note

Karyssa Gulish

Simone Munson

Robin Ryder

Lisa Saywell

Jonathan Senchyne

Libby Theune

Thank you:

Carole Askins

Susan Barribeau

Tom Caw

Jim Dast

Yoriko Dixon

Lee Grady

Works Referenced:

15 Forgotten Things Found Inside Books. (2018, November 28). Retrieved December 6, 2019, from https://www.messynessychic.com/2013/11/21/15-forgotten-things-found-inside-books/

Brookline Booksmith. (n.d.). Brookline Booksmith UBC Find Archive. Retrieved December 6, 2019, from https://web.archive.org/web/20150905080416/https://www.brooklinebooksmith.com/findarchive.htm

Cambridge Library Collection. (2014, July 17). Things You Find In Books. Retrieved December 6, 2019, from https://cambridgelibrarycollection.wordpress.com/2012/10/23/things-you-find-in-books/

Campo, K. (2014, March 11). Caught by Surprise: Letter Found in Rare Book Collection. Retrieved December 5, 2019, from https://www.mei.edu/publications/caught-surprise-letter-found-rare-book-collection

Davies, R. (n.d.). Things Found in Books. Retrieved December 5, 2019, from https://www.abebooks.com/docs/Community/Featured/found-in-books.shtml

Depompei, E. (2019, September 17). Taco left inside book at La Porte County library goes viral. Retrieved December 7, 2019, from https://eu.indystar.com/story/entertainment/2019/09/17/taco-book-la-porte-county-library-indiana-goes-viral-the-late-show-stephen-colbert/2353465001/

Doherty, T. (2014, January 6). The Paratext’s the Thing. Retrieved December 5, 2019, from https://www.chronicle.com/article/The-Paratexts-the-Thing/143761

Drucker, J. (1995). The Century of Artists’ Books. New York, New York: Granary Books.

Drucker, J. (2018, January). History of the Book – Chapter 5. The Invention and Spread of Printing: Blocks, type, paper, and markets. Retrieved December 5, 2019, from https://hob.gseis.ucla.edu/HoBCoursebook_Ch_5.html

Faircloth, K. (2015, February 6). Bookstore Seeking to Return “Heartfelt Letter” Found in a Used Book. Retrieved December 4, 2019, from https://jezebel.com/bookstore-seeking-to-return-heartfelt-letter-found-in-a-1684267807

Flood, A. (2019, August 21). Bacon, cheese slices and sawblades: the strangest bookmarks left at libraries. Retrieved December 7, 2019, from https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2018/may/14/bacon-cheese-slices-and-sawblades-the-strangest-bookmarks-left-at-libraries

Hanagarne, J. (2015, August 3). Surprises Found In Library Books. Retrieved December 5, 2019, from https://bookriot.com/2015/08/04/surprises-found-library-books/

Hanagarne, J. (2015, December 14). Surprises Found In Library Books (or Libraries): Part Deux. Retrieved December 5, 2019, from https://bookriot.com/2015/12/14/surprises-found-library-books-libraries-part-deux/

Kowal, R. (2014, December 6). These Gorgeous Love Letters Found In Used Books Will Seriously Make You Swoon. Retrieved December 6, 2019, from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/vintage-love-letters_b_5916384

Monson, A. (2015). Letter to a Future Lover: Marginalia, Errata, Secrets, Inscriptions, and Other Ephemera Found in Libraries. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Graywolf Press.

Morris, J. (n.d.). In This Land of Sun and Fun. Retrieved December 5, 2019, from http://foundmagazine.com/find/in-this-land-of-sun-and-fun/

Popek, M. (2011). Forgotten Bookmarks: A Bookseller’s Collection of Odd Things Lost Between the Pages. New York, New York: Perigee.

Popek, M. (2012, January 3). The Weirdest Objects Found Inside Books. Retrieved December 6, 2019, from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/objects-found-inside-book_b_1070447

Price, L. (2019). What We Talk About When We Talk About Books: The History and Future of Reading [pdf]. New York, New York: Basic Books.

Stern, J. (2019, March 1). The Strange Things I’ve Found inside Books. Retrieved December 5, 2019, from https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2019/02/27/the-strange-things-ive-found-inside-books/

THOMSON PRESS-Digital Printing Services-Printing Press India. (n.d.). Thomson Press, Digital Printing Services, Books Printing, Magazines Publishing, Web Offset Printing,Print Media, Typesetting Services, Color Printing, Books Binding, Printing Press India. Retrieved December 6, 2019, from http://www.thomsonpress.com/

University of Virginia Book Traces. (n.d.). Book Traces at UVA. Retrieved December 4, 2019, from https://booktraces.library.virginia.edu/

Werner, S. (2019). Studying Early Printed Books, 1450-1800: A Practical Guide. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley.